Bart Pfankuch / South Dakota News Watch

SISSETON, S.D. – All it took in spring 2024 was two small, unrelated medical service interruptions to put women’s health at risk and expose the fragility of the health care system in rural and reservation communities across South Dakota.

First, the local public hospital in Sisseton, the Coteau des Prairies Health Care System, cut back its OB/GYN program and stopped delivering babies due to relocation of its obstetrician, high expenses and because a low number of annual deliveries raised concerns over the expertise level of existing medical personnel.

Meanwhile, the Indian Health Service hospital in Sisseton, a reservation community of 2,400 people in the northeast corner of South Dakota, for a time did not have anyone certified to operate its mammogram machine.

While the public hospital and IHS took steps to minimize the disruptions, it became more difficult for female tribal members to get screened for breast cancer. And any pregnant woman who wants a hospital delivery will now have to drive an hour to Watertown or Fargo, North Dakota, to give birth.

“When it comes to obstetrics in northeastern South Dakota, we’re in a maternity care desert here right now,” said Sara DeCoteau, tribal health coordinator for the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate tribe.

Similarly, in the far northwest corner of South Dakota, when a physician who worked for 15 years at a Horizon Health clinic in Bison moved to Sioux Falls to be closer to his grandchildren, it took nine months to find a replacement doctor.

While Horizon expanded use of telehealth services and brought in providers when possible to see patients in Bison, there was no question that patient care in the remote, rural ranching area was disrupted during the absence.

“That’s a one-provider practice. And when one thing breaks in the chain, it creates this question all of a sudden of, ‘Now what do we do?'” said Wade Erickson, CEO of Horizon Health. “We’ve got to get creative and think outside the box because everybody, regardless of where you live, work or raise your family, deserves access to primary health care. And you shouldn’t have to sacrifice health care if you choose to raise your family in a rural setting.”

And yet, many rural and reservation residents in South Dakota and other states are suffering devastating, often preventable, negative health outcomes due to a variety of barriers to obtaining health care in their communities.

Long driving distances, a shortage of medical staff in Indian Country and farm country and the expense of maintaining medical facilities in low-population areas all prevent the estimated 46 million Americans who live in rural areas from getting the health care they need to live healthy lives.

Major findings of a News Watch project

As part of a fellowship granted by the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, News Watch spent several weeks conducting interviews, examining data and traveling the state to learn about the barriers to health care across rural areas of South Dakota.

Here are four major findings:

- A variety of barriers do exist to obtaining preventive, primary, emergency and specialist health care in rural and reservation communities across South Dakota. And those barriers are leading to higher prevalence of disease and illness and overall increased mortality rates.

- The health care system now in place in those regions of South Dakota — while staffed and led by caring providers who expend great energy, innovation and compassion to provide patient care — still faces significant challenges and is quite fragile in that one small interruption or deficiency can lead to a host of new negative outcomes.

- The barriers to health care access in rural and reservation communities is not unique to South Dakota and can be primarily split into two major categories: barriers that prevent providers from helping as many people that they would like and barriers on the patient side of the equation that can slow or even block access to needed health care.

- Solutions to the problems are not easy to come by. But increased focus by the health care industry, state and national policymakers and the public has led to potentially replicable successes that can improve a complicated yet well-intended system that seeks to keep people healthy.

Data reveal deep health disparities

Multiple national and state reports and data sets show that rural and reservation residents suffer poor health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts.

According to a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the death rate in rural areas of the U.S. was 21% higher than in urban areas in 2019, and the mortality disparity grew larger over the past decade despite major improvements in medical care and technology.

Death rates in rural areas were higher than urban areas for heart disease, cancer, injuries, respiratory disease, stroke, diabetes, suicide and other causes, the study found.

So-called social determinants of health, which include poverty, lack of education and job opportunities, and limited access to healthy food play a role in why some people are healthier and live longer than others.

However, experts said, a lack of access to health care remains a major factor in that equation. And nowhere is that barrier larger than in rural and reservation regions of the U.S.

“Rural health is America’s health, and we need policymakers to understand that the American Medical Association (AMA) is deeply concerned about the ever-widening health disparities between urban and rural communities,” Bruce A. Scott, M.D., president-elect of the AMA, said in a recent online conference attended by News Watch.

“I worry that the health outcomes in rural America will continue to decline even faster … where so many of the systems and the physicians are already teetering on the brink,” he said.

Problems ‘magnified’ on reservations

When asked by News Watch about barriers to health care in indigenous communities, Scott said the health disparities that exist between urban and rural residents are even worse among Indigenous populations.

“The problems that I mentioned are all at play here, but they’re manifest and magnified” in Native populations, he said.

Data from the South Dakota Department of Health (DOH) illustrate the depth of the health care disparities between Native and non-Native residents of the Rushmore State.

The DOH reports that while 50% of white South Dakotans will die before the age of 80, half of all Native Americans in the state will die before the age of 58. Native Americans have much higher rates of cervical cancer, lung cancer and incidence of syphilis, a growing health crisis in reservation areas.

According to IHS, residents of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwest South Dakota face far higher mortality rates than non-Native state residents, including from diabetes (800% higher rate), alcoholism (550% higher rate), cervical cancer (500% higher rate) and infant mortality (300% higher rate).

In South Dakota, Native American infant mortality (17.2 deaths per 1,000 births) is more than four times higher than for white infants (3.9 deaths per 1,000 births), and the disparity has grown far worse over the past five years.

A 2022 report by the American Hospital Association said access to health care in non-urban areas has worsened due to the closure of 136 rural hospitals in the U.S. between 2010 and 2021, including a record 19 closures in 2020.

That report cited factors that are playing out regularly in South Dakota, including low Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates, staffing shortages, increasing costs for providers, regulatory hurdles and low patient volumes.

Scott added that the health care industry must also acknowledge, and work to overcome, barriers that some Native Americans face due to distrust of the medical system due to racism and historical trauma as well as hesitancy to engage with providers who often do not share their culture or backgrounds.

“We have to recognize, and the AMA is acknowledging upfront, the years of discrimination and racism that these populations have faced,” he said. “The AMA is working through our Center for Health Equity to eliminate those inequities and to face those inequities up front.”

State launches mobile health program

State officials in South Dakota are aware that some areas are woefully underserved with health care.

DOH recently launched a new program, called Wellness on Wheels, to provide mobile health services to rural communities across the state, particularly those “facing socioeconomic barriers and social determinants of health.”

DOH Secretary Melissa Magstadt told News Watch in an interview that the mobile clinics, which will provide immunizations, testing for sexually transmitted diseases, and birthing and parental services, will bridge gaps caused by geography and lack of available services in rural areas.

“The minute we make the challenging system more difficult than it already is by adding one more barrier, it becomes harder for people to do the right thing even when they want to,” Magstadt said. “Those barriers may seem small to many of us, but if you’re a single mother with four children or you have to work or don’t have a way to travel an hour, it becomes less likely for them to get health care, and I don’t blame them one bit.”

The vehicles, equipment and staffing for the five mobile clinics were paid for with one-time federal funds given to South Dakota during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the state used some money from its federal Women, Infants and Children program allocations to also aid in finding, Magstadt said.

One of the five mobile health buses will primarily serve Sioux Falls and another in Rapid City, while the other three will travel the rest of the state based on population and need, Magstadt said.

Her next goal is to forge partnerships with existing health care providers to allow the mobile clinics to set up where people are already receiving necessary services, which could include working with rural grocers so families can get food and basic health care at the same time.

“It’s literally returning to the roots of taking health care out to the patients,” Magstadt said.

Long-term worker shortage worsening rural health care

A significant and worsening challenge in health care everywhere is a shortage of physicians, nurses and other providers. And the problem is the worst in rural and reservation areas.

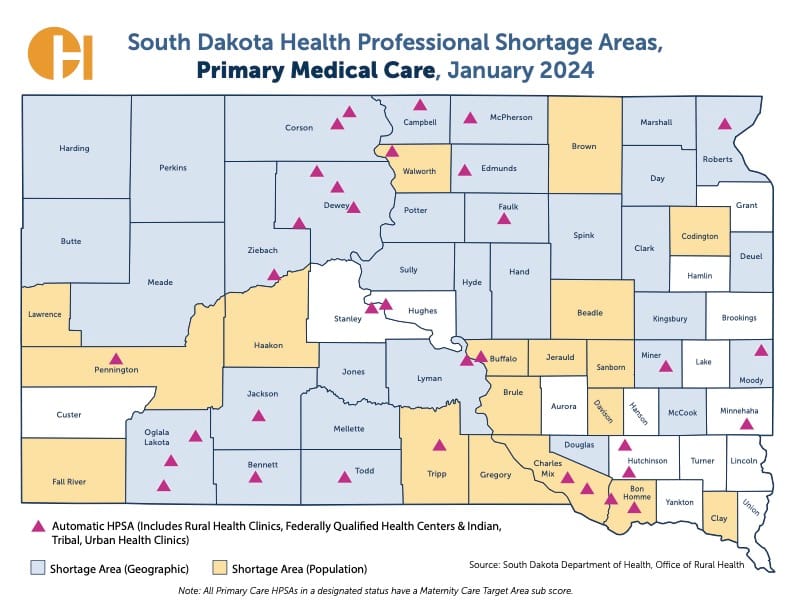

In South Dakota, only 15 of 66 counties did not have a shortage of primary health care providers in January, according to the state Office of Rural Health. The vast majority of the underserved areas are outside urban centers.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has (AAMC) recently estimated that the U.S. will see a shortage of 87,000 physicians nationwide by 2036, due in part to mass retirement of aging doctors and a lack of medical school graduates to replace them.

In recent publications, the AAMC and AMA pointed to several factors that make the shortage worse in rural areas:

- Massive student debt accumulated by medical students makes it less likely they will practice in rural or reservation areas, where pay is often lower than in cities.

- Rural providers often work alone or without direct supervision, and training opportunities are limited for providers who want to develop a speciality or advance their skill set.

- Rural patients tend to be older and have more complicated health problems.

- By nature, rural and remote areas provide fewer social opportunities, shopping, recreational and restaurant amenities, or employment options for spouses of medical workers.

According to the National Rural Healthcare Association, for every 10 physical specialists in urban areas, there is on average one physician specialist in rural areas of America.

“The worsening health care worker and physician shortage of primary care and specialists, particularly in the rural areas, are exacerbating these (health) concerns and creating health care trends that are simply unacceptable,” Scott said.

In 2012, the state launched two efforts to recruit more health workers to rural or underserved areas:

- The Rural Healthcare Facility Recruitment Assistance Program gives certain practitioners a $10,000 payment if they work three years in a community of under 10,000 population. It has had 840 total applicants since inception, and as of early this year, 524 medical workers have completed or remain enrolled in the program.

- The Recruitment Assistance Program provides payments ranging from $71,000 up to $256,000 for dentists, doctors and other practitioners who spend three years in communities under 10,000 population or in great need of services. So far, 20 dentists, 69 physicians and 50 others have completed the program.

Taken together, the programs have cost the state about $5.6 million in payments over the past five years, according to the DOH.

Long distances, limited service hours

The issue of geographical challenges and the need to travel to get preventative, emergency or specialist care has hampered health care access in rural areas for generations.

The problem is particularly acute in reservation communities where poverty rates are far higher than average and owning or obtaining transportation for a local medical appointment, let alone a specialist visit in a city far away, can be daunting.

“We complain about not having enough services in our bubble in Rapid City, but what about having to drive an hour or two for help,” Michelle Comeau, a wellness navigator with the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, said at a recent community meeting in Rapid City. “But outside of here, a gas card can be the difference between life and death.”

On two small reservations in central South Dakota and in many small towns across the state, primary medical care is available only during daytime hours on weekdays.

On the Crow Creek Indian Reservation and the Lower Brule Indian Reservation just across the Missouri River, both home to main cities with about 1,000 population, primary health care is administered at IHS clinics that are open from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday. Horizon Health also operates a clinic in a small building in Fort Thompson that is open only during daytime hours on weekdays.

In those communities and many others across the state, someone with an emergency or a pressing health care need is told to call 911 or a local ambulance service, many of which face their own set of staffing and financial issues.

In Fort Thompson or Lower Brule, that would require wait time for an ambulance, then a 30-mile ride mostly on winding two-lane roads to the Sanford Chamberlain Medical Center, where a 24/7 emergency room awaits.

In Faith, a ranching town of 600 in west-central South Dakota, medical care is also available only during daytime hours Monday through Thursday at a Horizon clinic staffed by a family nurse practitioner.

If the clinic is closed or in-person specialist care or surgery is needed, patients might need to make a 250-mile round trip journey on two-lane roads to Monument Health Rapid City Hospital.

Boy’s death reveals rural health barriers

The limitations of IHS services and challenges in travel during a health emergency had tragic consequences in 2022 for Honor Beauvais, a 12-year-old boy living on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation who suffered from asthma.

In a previous interview with News Watch, Honor’s grandmother recounted how he was taken to the IHS emergency room in Rosebud on Dec. 14, 2022, with flu symptoms and breathing difficulties. He was evaluated, given medicine and released. He stopped breathing the next day and died, with massive snowdrifts preventing an ambulance from reaching the family’s ranch until it was too late.

Honor’s grandmother contends that her grandson should have been held at the hospital rather than released due to severe weather and the probability that follow-up care would be needed. The family is pursuing a lawsuit, including against IHS, which refused to comment for that News Watch article or for this one.

Health secretary: Holistic approach needed

Providing health care is only one part of the larger equation that leads to a healthy life and greater life expectancy, said DOH Secretary Magstadt.

Medical care access is only about 20% of the overall health spectrum, which also includes living environment, personal choices in terms of diet, exercise and habits, Magstadt said. One-third of the equation is due to social determinants of health, which includes education level, employment, transportation options and access to healthy foods.

Magstadt said the state can take steps to provide greater access to public health initiatives that reach a wide range of people, including through efforts to increase access to immunizations, education on child development and safe sleeping and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. The state’s new Wellness on Wheels initiative is one example of improving public health, she said.

But it will take wider efforts, Magstadt said, to reduce the impacts of social determinants of health in rural and reservation areas, including by improving public health, increasing job opportunities, encouraging development of affordable quality housing, creating more safe places for children to play and learn, improving transportation options and finding ways to offer more healthy food to people in remote areas.

“The socio-economic and social determinants of health have been an under-evaluated piece of the equation that we in health care haven’t taken fully into account,” she said. “If you don’t have those things in place, then it’s impossible for people to do the healthy behaviors that are part of the 80% of a healthy life that takes place outside the health care system.”

To make more people aware of challenges in indigenous health care, the DOH publishes a web page called the American Indian Health Data Book that includes a variety of data showing the health disparities between Native Americans and white residents of South Dakota.

The agency has also undertaken a wide-ranging analysis of the rural health care system in the state and hopes to have a final report, with recommendations for improvements, completed by the end of 2024.

Magstadt said her department is also highly focused on working in partnership without other entities to make holistic improvements in communities, including in reservation areas.

“If we’re only tied into what health care can do, we can feel very discouraged,” she said. “But if you come to this with a greater aperture of what we can all do together, we can start to pull the levers that will lead to positive outcomes.”

Better health care, stronger communities

On a recent weekday afternoon, Erickson, the CEO of Horizon Health, strolled through his system’s clinic in Martin, in southwest South Dakota, and was proud to show a visitor the range of services provided.

The small clinic has an X-ray machine, offices for patient consultations or minor procedures, telehealth equipment and a small laboratory that looks more like a kitchen counter in an apartment than a modern medical lab. A physician and two mid-level providers split time to serve patients on an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. basis on weekdays.

Erickson said Martin, a farm and ranch city of 950 people located 120 miles southeast of Rapid City, is fortunate in that it is home to the Horizon clinic, an IHS clinic and the Bennett County Hospital, which has an emergency room and 24/7 care options.

Erickson said even though Horizon clinics have limited hours of operation, all clinics provide emergency phone access at anytime for patients who need to speak to a provider when clinics are closed.

He also explained how telehealth services can provide patients in remote areas with a range of services from behavioral health, to diagnosis of ear, nose or throat illnesses to analysis of blood work or vital signs by a remote physician or specialist.

Horizon, based in Howard, plays a critical role in filling the gaps in rural and reservation health care in South Dakota.

The not-for-profit health system has 31 health or dental clinics in 22 communities, covering a 28,000 square-mile service area with nearly 30,000 patients undergoing 100,000 clinic visits a year. Horizon operates on six of the nine American Indian reservations in the state.

Erickson said Horizon clinics seek to provide patients with primary and preventative care that will stave off more serious medical conditions and then triage patients who need more help and set them on a course to obtain more invasive care elsewhere.

He sees his clinics as necessary for human health but also to help keep rural and reservation communities viable and thriving.

“There’s certain things that younger families need and want within their communities, so you’ve got your gas stations, grocery stores, your Main Street business, your school district, your churches and your health care,” he said.

“In South Dakota, west of the (Missouri) river, it’s an hour between every community, so if you don’t have health care, it’s two hours or more to get to the next level of care. And without some health care access in those towns, how are we going to keep our rural communities sustainable?”

Despite its extensive network in mostly underserved areas, Erickson acknowledged that a better, more comprehensive system of health care is needed to ensure quality patient care throughout rural South Dakota.

Stronger relationships and greater cooperation among rural clinics, small-town hospitals and major health providers in Sioux Falls and Rapid City are one way to reduce barriers to rural health, he said.

“It’s not OK as it is. And we have to figure out a way to fix that because people don’t just get sick from 8 to 5,” he said.

“Having a rural hospital is such a key piece of the equation because if a patient has stroke symptoms or they’re having chest pain, being an-hour-and-a-half to two hours from the closest hospital might be too far. And that might not turn out well.”