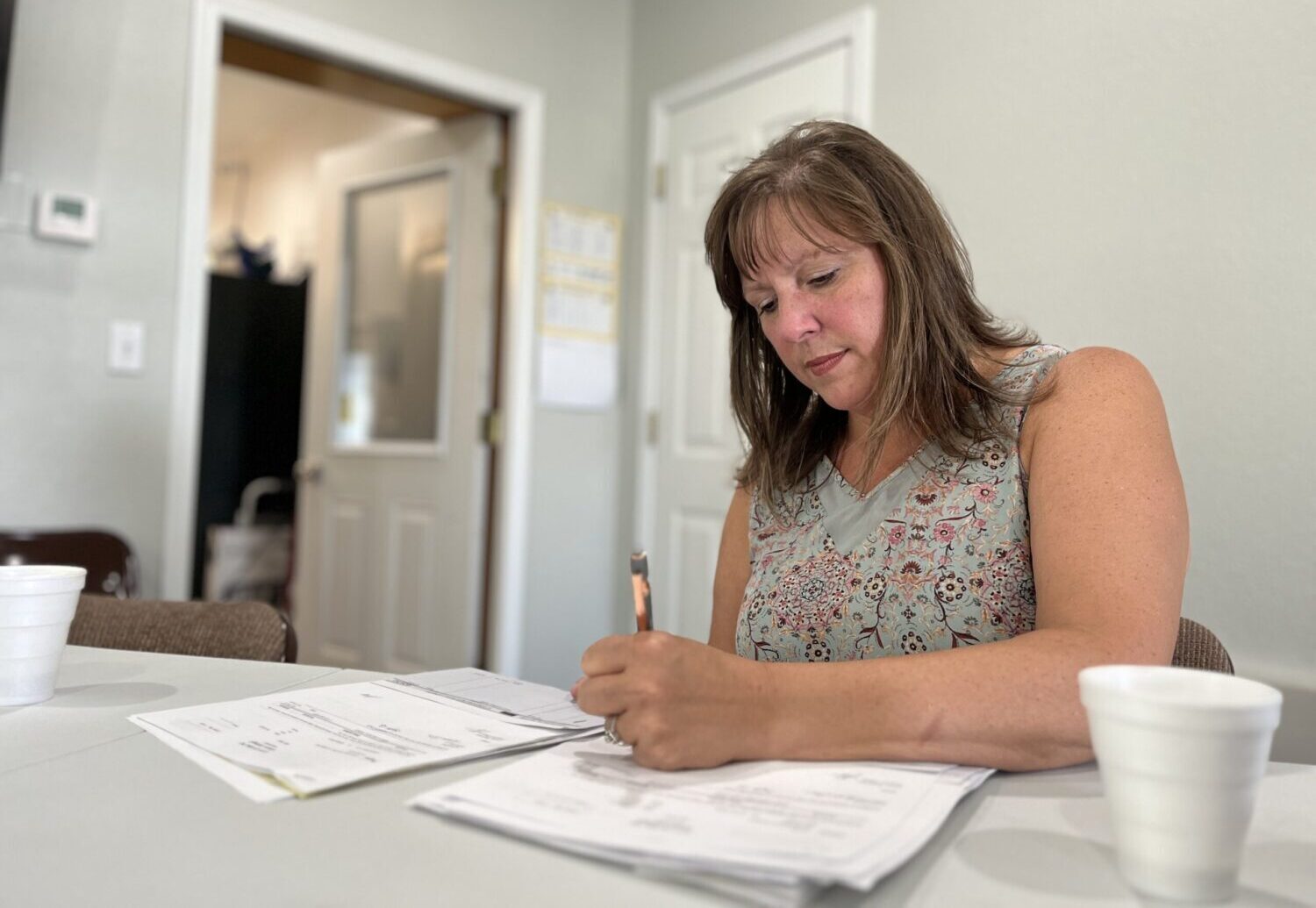

(Joshua Haiar/South Dakota Searchlight)

BALTIC — Mayor Deborah McIsaac said she was shocked when she took office in 2022 and discovered a housing development in town had been given the green light without basic paperwork ensuring accountability.

“I’m like, ‘seriously?’” McIsaac said.

The situation evolved into a political crisis — including a failed mayoral recall — for the town of about 1,300 residents, which is less than 20 miles north of Sioux Falls and that city’s rapidly growing population of about 200,000.

As Sioux Falls sprawls toward nearby small towns, they could experience growing pains similar to Baltic’s if local governments don’t take precautions.

The Baltic situation began in 2020 when a hometown housing developer initiated a 127-lot housing development and promoted its proximity to Sioux Falls.

When a development is proposed, many municipalities establish a development agreement, which spells out who is obligated to do what — responsibilities such as regulatory compliance, title assurance and inspections. They might also establish a performance bond, which ensures that if a developer doesn’t complete a project as agreed, the municipality will get money to finish the job or fix any problems.

Baltic City Attorney John Hughes — who was the attorney when the city began work with the developer — said the mayor and council in charge when the development began ignored basic requirements of sound development and apparently thought a “handshake deal” would suffice instead of a formal development agreement.

The developer declined to comment for this story.

Runoff and drainage problems, litigation

Not having basic documentation makes enforcement and accountability less black and white, Hughes said. He resigned on Feb. 6, 2021, due to concerns about how the city and development were being managed.

“Who wants to be part of a process that lacks integrity?” Hughes said. He was later rehired by McIssac after she became mayor in 2022.

McIsaac said the development was not constructed to meet basic standards, which resulted in runoff and drainage problems. The state Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources determined the developer was not obeying water runoff and erosion rules and required the developer to address the problems and pay $46,283 in civil penalties.

Additionally, when the city council voted to pause additional development to reassess its protocols, the developer responded with litigation against the mayor, city council members and members of the Planning and Zoning Commission, alleging that the city was undermining its own economic development.

The matter ended with the developer paying a $735,000 settlement and agreeing to construct a detention pond to prevent more runoff. In turn, the city had to remove its suspension on building permits.

Controversy arising from the situation led petitioners to subject McIsaac to a recall election last month. She survived by a vote of 301-224, with 67% voter turnout.

McIsacc said the city is still struggling to force the developer to comply with its development standards – pointing to problems with weeds, gravel road degradation, and improperly constructed curbs.

Hughes said small towns near growing cities should heed the example of Baltic and “beef up their ordinances and regulatory oversight,” or they could be next to go through a similar drama.

Other towns say they’re ready

Steve Britzman is the city attorney for Brookings, with about 40 years of experience providing legal guidance for towns including Aurora, Volga, Elkton, Sinai and Bushnell. He said small towns with limited resources and staff can find themselves wrestling a developer with more cash on hand than the city budget – like Baltic’s approximately $850,000 annual budget.

“It’s always challenging when a big company comes to a small community,” Britzman said. “These communities are left to be more or less reactive.”

He said that’s because regulatory oversight and enforcement are unlikely to be something a small town can afford to do adequately.

“You can’t expect a finance officer, who is also the city administrator, to also handle the technical issues,” Britzman said. “In a sense, you’re left relying on the developer to do the job right. That’s why you want to work with a developer you’re certain you can trust.”

However, many small-town officials surrounding Sioux Falls say they are confident their town can handle rapid development. Jessica Fueston is the economic development coordinator for Garretson, which has a population of approximately 1,200 about 20 miles northeast of Sioux Falls.

“A lot of what makes the difference goes back to having a city council and mayor that have a real hands-on approach,” Fueston said. “That’s what is most important — having people who are truly involved.”

Fueston said leaders must be thorough. And while it may be a slower process than in a city with more staff, developers “have to adopt our rules.”

“We understand that it can be a headache for them, but we need to do it right, from the beginning,” she said.

‘Days of a handshake deal are over’

Tom Earley is the mayor of Dell Rapids. He said municipalities need to “have procedures institutionalized,” meaning that basic standards are practiced regardless of the developer or situation.

“The days of a handshake deal are over,” he said.

Earley said Dell Rapids has managed growth well because of its partnership with the Southeast Council of Governments (which helps navigate grants and paperwork) and its contract with DGR Engineering (which ensures any development meets engineering standards).

A contracted engineer is something Baltic now has, but could have used when its controversial development began, according to McIsaac. Baltic is not a member of the Southeast Council of Governments.

“What fixes this is a strong city engineer,” McIsaac said, explaining that they help craft a comprehensive plan, “and of course, you have their expertise to back everything up.”

Glenda Blindert is the mayor of Salem, which has about 1,300 residents 40 miles west of Sioux Falls. She said Salem’s approach to its latest 12-acre, 35-lot housing development has been nontraditional.

She said Salem’s economic development corporation is developing the water and sewer lines and roads, and then selling the lots to people who want to build a house, without a private developer involved.

“This is how I think you’ll see a lot more of these small towns do it going forward,” Blindert said.

To fund the infrastructure, Blindert said Salem is hoping to be awarded some of the $200 million in housing infrastructure money the state recently started granting.

“Otherwise, these projects just get so expensive for a small town,” she said.