Joshua Haiar/South Dakota Searchlight

A second group has formed in response to disputes over a proposed carbon dioxide pipeline in South Dakota, this time in support of policies that could result in the pipeline’s construction.

A news release from the newly formed South Dakota Ag Alliance said it will “mediate and advocate for reasonable solutions to difficult ag and rural development issues” such as carbon pipeline proposals. That includes advocating for policies to provide a better deal and greater peace of mind for affected landowners.

Co-founders Rob Skjonsberg and Jason Glodt are prominent figures in South Dakota politics.

Glodt formerly did governmental affairs work for a carbon pipeline company, Navigator CO2, that has since terminated its proposed project. He is a lawyer and co-founder, with Skjonsberg, of GSG Strategies, a government relations, advocacy and campaign strategy firm. Glodt also served in the administrations of Governors Mike Rounds and Dennis Daugaard.

Skjonsberg, a rancher and farmer, formerly worked as chief of staff for Rounds, served on the state Board of Economic Development Board under Daugaard and worked as a senior vice president of government affairs for the Poet biofuels company.

The two said they are not being paid by anyone to lead the new nonprofit, and they’re not working with Summit Carbon Solutions, the remaining company proposing a carbon pipeline in the state.

“I haven’t said anything to them,” Skjonsberg said.

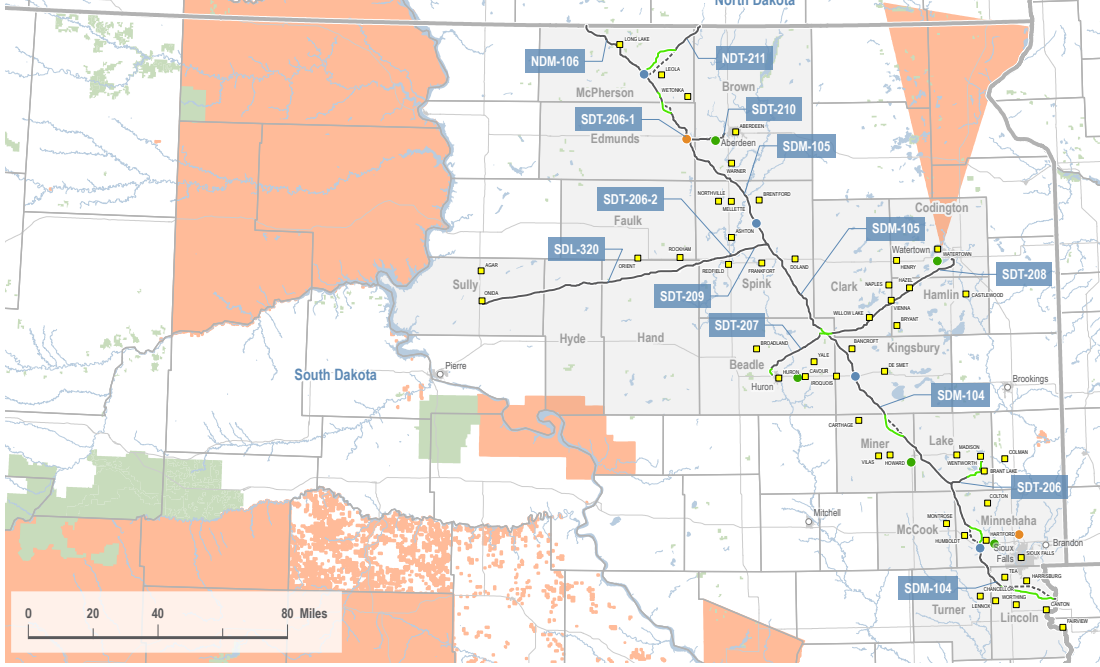

Summit, based in Iowa, wants to collect carbon dioxide emissions from 32 Midwest ethanol plants, including some in South Dakota. The carbon would be liquefied and transported through a multi-billion-dollar pipeline for burial in North Dakota, making the project eligible for federal tax credits that incentivize the removal of heat-trapping gasses from the atmosphere.

The South Dakota Public Utilities Commission rejected Summit’s permit application in September, citing problems including the route’s conflicts with county ordinances that require minimum distances between pipelines and existing features. The company plans to adjust its route and reapply.

Last month, the coalition South Dakotans First formed to protect property rights for landowners in response to Summit’s earlier filing — and later withdrawal — of eminent domain actions against more than 150 landowners. “Eminent domain” refers to the power to access private property for public use, provided the owner is justly compensated.

South Dakotans First includes the South Dakota Farmers Union, Dakota Rural Action, Landowners for Eminent Domain Reform and various landowners.

Glodt and Skjonsberg announced their new nonprofit Thursday as the South Dakota Farmers Union annual convention was happening in Huron. Farmers Union President Doug Sombke reacted to the news by phone.

“It’s Summit’s new public relations group,” Sombke said. “I mean, they still want to use eminent domain on us. Why should we negotiate when we won?”

During a convention panel discussion Thursday, landowner Ed Fischbach said South Dakotans First will support legislation including a ban on eminent domain for carbon pipelines. Similar legislation failed last winter at the Capitol in Pierre.

Glodt and Skjonsberg said they applaud a recent policy statement by the South Dakota Farm Bureau that says if a pipeline company has voluntary access agreements — called easements — with two-thirds of affected landowners, the company should be able to use eminent domain on the rest.

Glodt and Skjonsberg are additionally advocating for state legislation they say will protect landowner rights: reforms of land survey processes, liability protections for landowners, minimum depth requirements for pipelines, and ensuring additional recurring compensation for landowners.

They aim to provide legal and regulatory certainty for carbon pipelines.

“The government shouldn’t be able to move the goalpost after the deal is negotiated in good faith,” Skjonsberg said.

Skjonsberg also wants to replace the minimum setback distances for carbon pipelines adopted by counties with a statewide standard.

“At the state level, we should talk about setbacks,” Skjonsberg said. “You could end up with a complete hodgepodge of setback distances. And if you’re a company, how do you deal with that? It’s nonsense.”