John Hult, South Dakota Searchlight

SIOUX FALLS — Artificial intelligence (AI) could mean more efficient legal offices and lower bills for clients – provided human beings use the technology ethically.

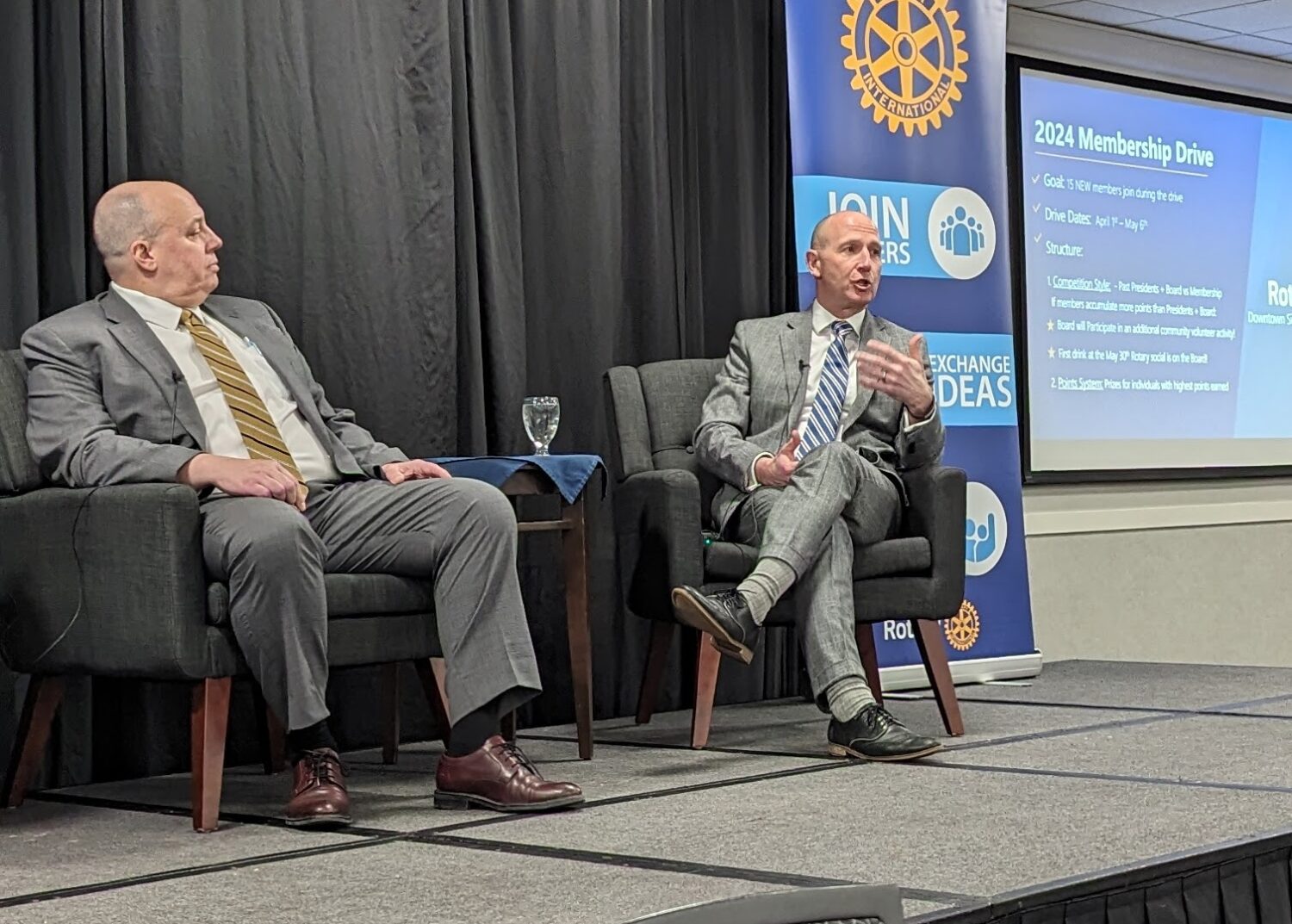

South Dakota Supreme Court Chief Justice Steven Jensen and University of South Dakota Knudson School of Law Dean Neil Fulton offered that tentative conclusion on AI in the legal profession to members of the Sioux Falls Downtown Rotary Club on Monday.

The law school is teaching AI to students and offering its law librarian as a trainer for practicing lawyers, Fulton said. The judicial system is considering ways the technology might improve efficiency, Jensen said, and not yet pondering regulations on its use by attorneys.

But both leaders agreed that human decision-making and judgment ought to be top of mind in the use of AI for legal work.

“I gave a speech to the class of 2024 on Friday, and the centrality of the human person to the law was the thrust of it,” Fulton said. “One of the things I tell them is that a lot of disciplines will just say, ‘Can we?’ The law has to step back and say, ‘Should we?’”

Some forms of AI have been a modern part of life for years. It undergirds consumer-facing tools like voice dictation on smartphones, spell checkers on word processors or chatbots that screen customer service queries and hold your place in line.

Public awareness of generative AI exploded mostly because of ChatGPT, a text creation tool released in November 2022. Generative AI involves asking a tool like ChatGPT (for text) or Midjourney (for art) to produce something. That could be a term paper, an image, a screenplay or a legal brief in a matter of seconds, though concerns about “hallucinations” – wherein an AI tool makes up facts to include in the final product – quickly emerged as a danger of relying too heavily on AI-only material.

In the legal field, AI tools have returned legal briefs citing cases that don’t exist. A federal judge in New York sanctioned a lawyer in that state last June for submitting briefs with phony citations.

“The running joke is now, ‘Did you write this brief, or did AI write it?’” said Barry Sackett, a Rotarian and lawyer who led the Monday discussion with Jensen and Fulton.

Sackett wanted to know how the chief justice and law school dean are thinking about the technology, given its prominence across multiple areas of work and play.

The initial stumbles with hallucination and worries of students using AI to cheat factored into some of Fulton’s first conversations about it with law school faculty in Vermillion.

That was a year ago. Now, Fulton said, the school works with – and teaches students about – the AI tools embedded in LexisNexis, one of two major legal research companies in the U.S.

Right now, he said, it can generate a brief that’s “about 50% accurate.”

“The human element is working out that other 50%,” Fulton said. “But that is a savings to your client. It’s a savings of time.”

Jensen agreed, saying it’s possible that AI could make offices efficient enough to shave dollars off legal bills. Lawyers often charge billable hours in 15-minute increments.

“We’ve not developed the rules, because frankly, if you start developing rules, sometimes you preclude innovation and the ability to improve what you’re doing,” Jensen said.

The state already has strict ethical standards on the truthfulness of evidence, he said. Those standards apply to any brief signed by any lawyer, regardless of whether someone on their staff or an AI tool helped write it.

“Are we getting briefs from AI right now? Maybe, and I don’t have a problem with it, as long as the lawyers are doing the homework to make sure that the briefs are accurate,” Jensen said.

He said the state has begun looking at ways to streamline certain processes for the sake of efficiency.

But there are lines to be drawn on AI and its use in the justice system, he said.

“We can’t depend mostly on a machine to decide cases,” Jensen said. “We can’t depend upon a machine to argue our cases. There’s so much of a human aspect in what lawyers do and what judges do that we have to make sure that that human aspect isn’t lost.”

Both leaders also told the Rotary Club that the law will need to keep up with the technology, wherever it winds up.

“We’re just like everyone else, in that we’re trying to figure this out as we go because it is moving so quickly,” Fulton said. “I think anybody who tells you they have this figured out is fibbing.”