Paul Hammel, Nebraska Examiner

WAYNE, Nebraska — A “reveal” of what a Nebraska poet hid inside a lonely monument a century ago revealed more of what Mother Nature could wreck over the span of 100 years.

On Saturday, descendants of John Neihardt revealed what they’d found inside an “altar to courage” that the poet and members of a fan club from what’s now Wayne State College planted in the rocky soil of northwestern South Dakota in 1923.

The homemade, concrete monument memorialized the courage of mountain man Hugh Glass, who was left for dead in August 1823 after being mauled by a grizzly bear but then crawled and limped 200 miles to get help.

Neihardt challenged students from Wayne State (then Nebraska Normal College) to return in 100 years to rededicate and open a time capsule he buried within the monument, which he said contained an “original manuscript.”

Drilled, chiseled into monument

His family carefully drilled and chiseled into the thigh-high monument last October after removing it from its location near Lemmon, South Dakota, where Glass was mauled.

But on Saturday they revealed that what they could retrieve from inside were still-wet fragments of a special Neihardt edition of a student newspaper, The Goldenrod, as well as pieces of Neihardt’s book containing his epic poem describing the heroic crawl, “The Song of Hugh Glass.”

Coralie Hughes, a granddaughter of Neihardt, said that despite the lack of a new work from Nebraska’s “poet laureate in perpetuity,” the family had accomplished its goal of fulfilling the “challenge” to open up the time capsule and not destroying the monument in the process.

“I was hoping for a personal note to the world from my grandfather,” Hughes said. “Maybe he did (leave one) because a lot of what we found was unintelligible.”

The paper fragments, when found inside a tin box imbedded in the concrete, were still wet, which she said may have been the result of several times when the monument was flooded.

The monument was originally built on dry, private ranch land near the confluence of two forks of the Grand River, but it ended up on the banks of a federal reservoir that flooded at least four times since 1953.

Hughes said the family was told by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which owns the reservoir, that the monument had to be moved if it was to be breached.

She said the family proceeded gingerly in drilling into the monument so as not to destroy it. The first thing to be discovered— using a snake-like video camera — were fragments of a pop bottle that contained a letter from two newlyweds— J.T. and Myrtle Young of Lincoln — who arrived too late to sign a document Neihardt said was signed by those present and placed inside a tin box.

The Neihardt family decided against trying to retrieve the glass fragments or trying to dig out all the paper fragments inside the embedded tin box for fear of destroying the monument, which was relocated to the John Neihardt State Historic Site in Bancroft, Nebraska.

Some papers remain inside the tin box, Hughes said, but they are just “crumbling” pieces.

“We didn’t want to keep going,” said Alexis Petri of Kansas City, who produced a short documentary on the family’s work to retrieve the monument.

Her documentary and the “reveal” were presented Saturday at the annual spring conference of the Neihardt Foundation held at Wayne State College. Neihardt graduated from the school, then called Nebraska Normal College, at age 15.

‘Wonderful to see something tangible’

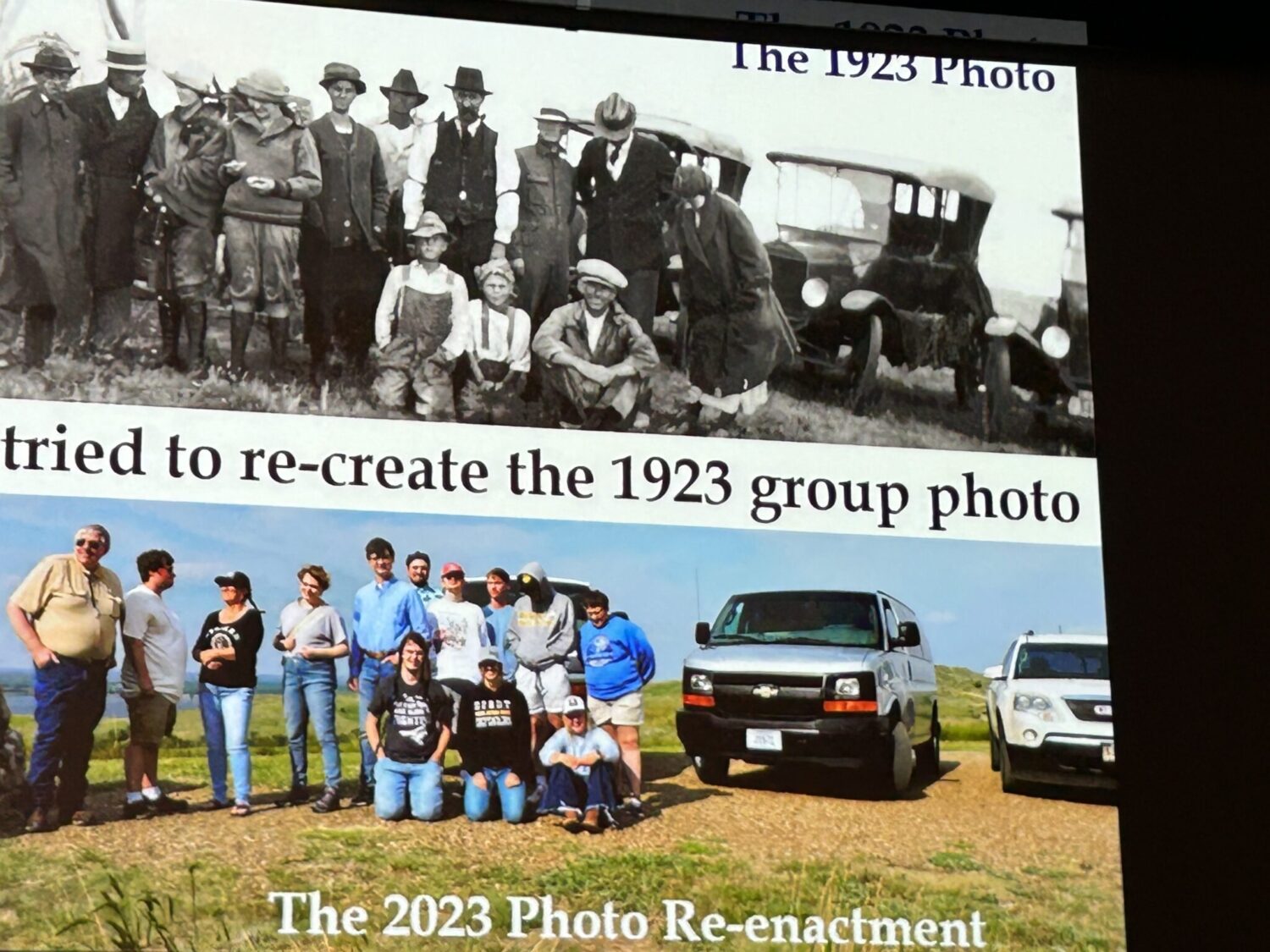

The event focused on the saga of the almost forgotten monument, the taking up of the challenge by Wayne State professor Joseph Weixelman and his class to rededicate the monument and the eventual decision to relocate the monument to Nebraska.

Mary McDermott, who drove from Holdrege with her daughter to view the final chapter in the mystery of the monument, betrayed no disappointment that some rare manuscript wasn’t found.

“It’s wonderful to see something tangible from 100 years ago,” she said.

“I’m impressed that there was something still there,” said her daughter Alizabeth.

Marianne Reynolds, the executive director of the Neihardt Center, said the fragments retrieved would be sent to the Ford Conservation Center in Omaha for further analysis.

After that, she said, they would be put on display at the center in Bancroft. A kiosk is envisioned so that visitors can play the documentary produced by Petri, Reynolds added.