John Hult/South Dakota Searchlight

Years ago, domestic methamphetamine users would make their own drugs, sometimes shaking up cold medicine and camp fuel cocktails in plastic pop bottles.

The days of domestic drug production by way of local meth labs are long gone, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2024 National Threat Assessment, as well as interviews with numerous law enforcement sources in South Dakota.

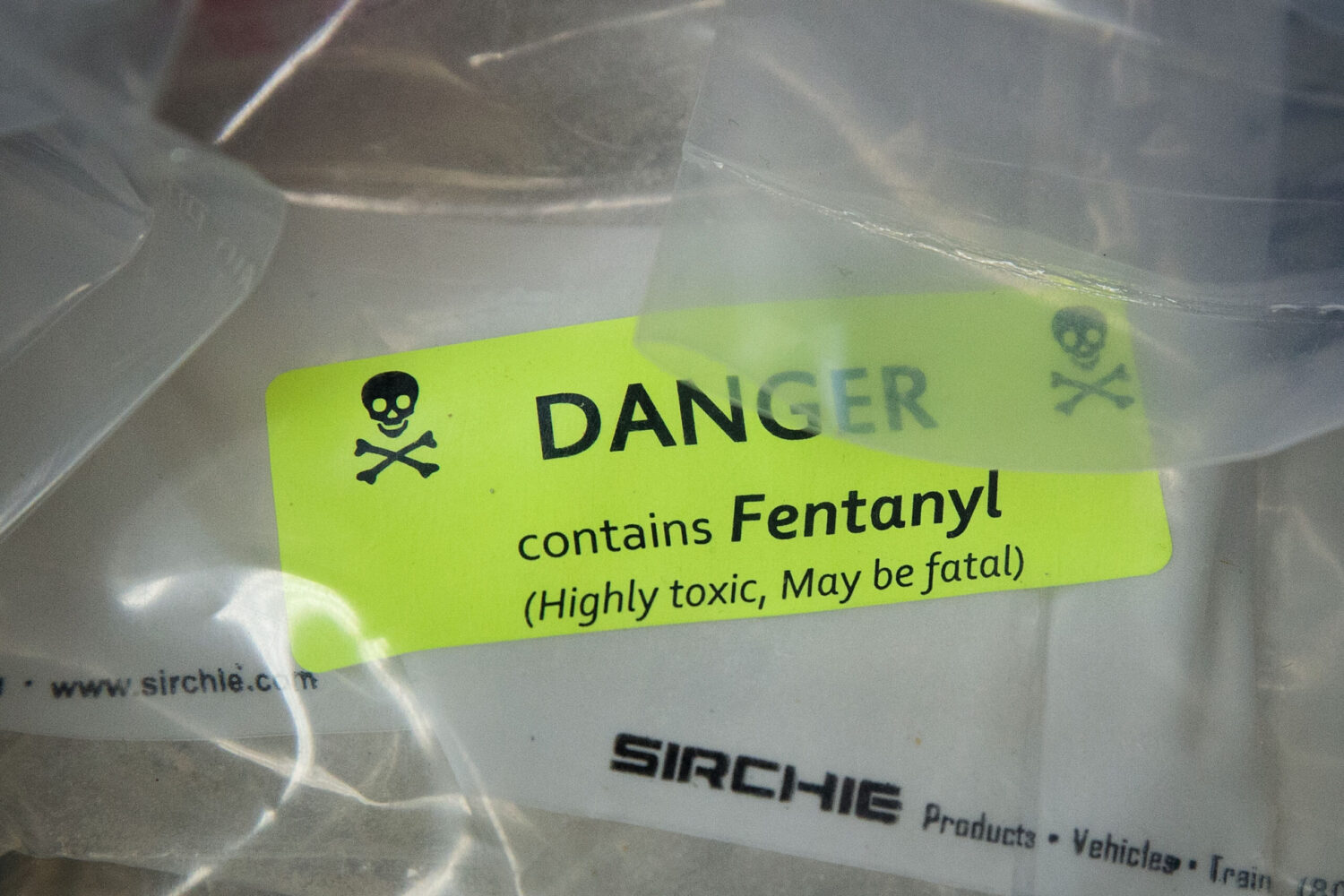

According to the DEA assessment, nearly all the nation’s meth, fentanyl, heroin and cocaine comes from across the southern U.S. border, and the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels in Mexico.

Those drugs – and the influence of the cartels that control the business, by extension – are everywhere, the DEA says.

The word “cartels” carries considerable weight in the current showdown between Gov. Kristi Noem and the state’s nine tribal nations. Noem has painted reservations as safe havens for cartel members and hubs of drug and human trafficking. She’s accused tribal leadership of personally benefiting from a cartel presence. Tribal nations have responded by banning Noem from their lands.

Brendan Johnson, a former U.S. attorney for South Dakota, said it’s unfortunate that the comments have some South Dakotans believing cartels are based on reservations, when in reality they’re targeting communities across the state.

“Suggesting that there’s some sort of pipeline between Mexico and the reservations is silly,” Johnson said. “It would be tantamount to saying, ‘Yeah, the cartels are really focused on Ipswich.’ That’s stupid, and people wouldn’t believe it. Unfortunately, people are more inclined to believe it (about reservations), because they have less knowledge on the reservations.”

Tribal leaders have rejected claims that reservations are the primary source or target for drug trafficking, and have called Noem’s remarks racist, divisive, unsubstantiated and discriminatory.

“Her remarks were made from ignorance and with the intention to fuel a racially based and discriminatory narrative towards the Native people of South Dakota,” Rosebud Sioux Tribal Chairman Scott Herman said in a March 15 statement.

South Dakota: Not a hub, but not immune

Steven Bell, based in Omaha, is the special agent in charge for a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration region that includes North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa and Minnesota.

In the Upper Midwest, it’s “lower population, fewer cases, fewer ties” to the cartels, he said.

“But it’s important to note that in all of the states, we have been able to tie back our investigative activity back to the cartel presence,” Bell said. “In our rural areas, we’ve developed information where we have actual individuals and undercover agents and officers in direct contact with known members of the cartel.”

There are a few other risk factors to consider in rural areas, Bell said, inclusive of tribal areas. First, drugs generally fetch higher prices in smaller communities, as they tend to be further from the source and users have fewer options for purchasing them. Second, there could be fewer law enforcement officers on patrol to notice trafficking.

Even so, Bell said, drugs generally flow from larger communities to smaller ones, not the other way around.

At least one truth applies to rural and urban areas: anyone captured with several pounds of a drug like meth is rarely more than a few steps removed from the cartel sources that mix it in clandestine labs for shipment to the U.S. – whether they know it or not.

“You might see a retail distributor just selling meth who may or may not have any knowledge of, truly, what organization they work for,” Bell said. “That’s where we come in and put the pieces of the puzzle together, because the cartels do that on purpose to minimize their exposure.”

Putting that puzzle together involves working with state, local and tribal law enforcement through joint powers agreements and groups like the Northern Hills Drug Task Force, according to Bell and others in federal law enforcement.

“We’re not targeting the end users,” Bell said of federal-level drug investigations.

Gary Gaikowski, police chief for the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, does see his officers interacting with a lot of users. But Gaikowski said his officers know that convincing people to talk about their suppliers – not a drug possession charge – is the endgame.

That’s where coordination with other agencies comes into play, he said. Users are more likely to believe they’ll be protected when they speak to the FBI or Division of Criminal Investigation, he said, because “it seems like they have more authority.”

Those agencies also have higher-level charges and penalties to use as bargaining chips for cooperation.

“It does help us when we coordinate with state authorities and work with the task force,” Gaikowski said.

Federal prosecutors: Hot spots are ‘fluid,’ drugs are in the mail

Large enough cases, on or off South Dakota’s reservations, land in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, where traffickers face mandatory minimum sentences more severe than they’d see in the state system. And that office also prosecutes all felonies that occur on reservations in the state, including drug and human trafficking cases.

The Major Crimes Act of 1885 gives jurisdiction for felonies to the federal government. Tribal courts handle misdemeanor offenses.

U.S. Attorney Alison Ramsdell and the assistant U.S. attorneys who specialize in drug prosecutions each offered assessments of the drug trade similar to Bell’s. So did Johnson and his predecessor, South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley, in separate interviews.

Aside from Johnson, none addressed Noem’s recent comments on drug cartels on tribal lands directly. But none suggested that reservations are hubs for narcotics.

Jackley declined to identify any drug hot spots that might have emerged in recent years. Such locations are fluid, he said. He also said the local, state, tribal and federal law enforcement players who cooperate to investigate the drug trade – and meet quarterly at Ramsdell’s behest – would rather not show their cards.

“If I were to pinpoint an area where the drug task force is working, then I would affect an operation,” Jackley said.

The biggest changes over the past decade have been the sheer volume of cheaply produced narcotics from Mexico and the disappearance of state-level meth cooks, according to Mark Hodges, a federal prosecutor who worked for former U.S. Attorney Ron Parsons, and now Ramsdell.

“So far, inflation hasn’t impacted the price of drugs,” Hodges said. “They’ve gone the opposite direction, because of the supply. There’s more of it, so it’s cheaper.”

There’s also been a spike in the purity of seized narcotics. In the past, couriers would cut Mexican dope with other chemicals during stops in cities like Phoenix, Kansas City or Omaha as their product made its way to more rural states.

Today, “when it gets to Sioux Falls or Rapids City, or Chamberlain, it’s 99% pure,” said John Haak, who leads federal drug prosecutions.

“To me, that indicates control from the central business, the main business,” Haak said. “They’re not letting it be cut.”

Haak echoed Jackley on the mobile nature of the drug business. Rural areas with few police officers and the potential for higher prices can be just as attractive as tribal land, while population centers mean access to larger markets.

“There’s not a fixed model that they use all the time,” Haak said. “They look for the cracks. If Trent works in one case, or Mitchell works in the next case, that’s what they do. The whole goal is to stay below the radar.”

Parsons would like to see more postal inspectors in South Dakota.

Traffickers send drugs through the U.S. mail, he said, because FedEx and UPS have more sophisticated screening processes. He testified to Congress about tribal law enforcement issues during his tenure as U.S. attorney and urged officials to hire more inspectors.

That hasn’t happened.

“There are only two postal inspectors in the entire state of South Dakota, and sometimes one of those positions isn’t filled,” Parsons said. “You could intercept a lot of drugs by putting a lot more scrutiny on the postal service.”

Dealer: System needs reform

One drug dealer recently sentenced to federal prison told South Dakota Searchlight she’s always tried to avoid reservations and to stay a few steps removed from cartels. The dealer spoke on condition of anonymity to protect her safety in prison, where revealing her methods could endanger her. Searchlight confirmed her identity and the details of her criminal record.

Mandatory minimum drug sentences for federal crimes – which applied to her after federal officials intercepted a mailed package of methamphetamine – are the reason she avoided reservations and their federal jurisdiction. Fear of violence is the reason she avoided cartel connections.

She worked with cartel sources in another state, she said, but found other ways to get drugs in South Dakota.

“The cartels don’t care,” she said. “They’ll kill your whole family. Women, babies, they’ll do it without batting an eye.”

A vulnerability for South Dakota is its geographic size and low population density, and the role those factors play in the price drugs can fetch. She described being able to buy an ounce of methamphetamine in California for $150 and then make 10 times that amount by breaking it up and selling it in smaller quantities in South Dakota.

Addiction is the heart of the market, she said, for buyers and sellers alike. She’s moved pounds of methamphetamine over the years but said she only got into dealing to support her own habit.

She tried to get into treatment or into one of the state’s drug courts several times but said she’d always been rejected, in part because of a violent crime on her juvenile record. Her stint in the South Dakota Women’s Prison in Pierre on a drug ingestion charge was supposed to include drug treatment, but she didn’t get it, she said.

What she did get was a chance to network.

“I didn’t know half the people I know here until I went to prison,” she said. “They connected me with the rest of the state.”

By the time she was arrested on a federal distribution charge in 2022, she was using an 8-ball of meth every day and sharing with friends, she said. An 8-ball is 3.5 grams, or $350 worth of product at South Dakota prices, she said.

She believes state-level dealers a few steps removed from higher-up players are almost always heavy users.

“They’re not moving weight because that’s what they want,” she said. “They’re moving weight because their habit is so f***ing deep and they can’t afford it otherwise.”

That’s how cartels and those linked to them get a foothold, she said. People desperate for drugs will let distributors use their home as a hub for sales – at least until the home catches the attention of police.

The shuffle of stash houses happens in tribal communities, she said, but “I know of 10 houses where it’s happened in Mitchell.”

DEA: Rural areas not prime trafficking spots, still face dangers

For the drugs that fuel the cartel trade, rural America has specific draws, even though its large-scale busts are smaller than they would be in metro areas.

Bell, the Omaha-based DEA agent, spent much of his career in Phoenix, where he said a 20-pound seizure of meth would be barely notable. In Atlanta in April, federal law enforcement seized more than 600 pounds of methamphetamine.

But 20 pounds of methamphetamine is significant for South Dakota. In a small state, 20 pounds can get a lot of people high and bring in bigger profit margins.

“When you take that off the street in small town USA, you are truly making a difference in the community,” Bell said. “In Phoenix where you have four and a half million people, it’s whack-a-mole. You get 1,000 pounds one day, and you get 800 the next. It’s never-ending.”

Bell knows all about meth-by-mail. But he doesn’t see more postal inspectors as a panacea, either. There are myriad methods for getting drugs into the U.S. that have been used by cartels. People have built ramps to jump border walls with vehicles filled with narcotics. Drugs are packed into shipping containers to cross borders with consumer goods, carried in boats or moved through underground tunnels. The DEA has intercepted drones and gliders carrying drugs.

“It goes to show how resilient these cartels are,” Bell said. “They have nothing but time and money to figure out the best way to get product into the United States and out to the rural communities, where they’re going to make the biggest bang for their buck.”