Stu Whiteney, South Dakota News Watch

DETROIT – Justin Roebuck can recall the exact moment that distrust of 2020 presidential election results impacted his status in the Republican Party.

The top election official of Ottawa County in western Michigan was speaking to a GOP women’s group when he was asked who won the race between Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden in the Midwest battleground state.

“When I told them that Biden won Michigan by about 154,000 votes, the gasp was audible in the room,” said Roebuck, adding that he was castigated by other party members for legitimizing the results. “I think it hit home for me at that point.”

Roebuck was among a group of election officials who spoke to journalists as part of the National Press Foundation 2024 Elections Fellowship in late July, assessing the state of American voting systems ahead of November.

They illustrated how unfounded claims of voter fraud, exacerbated by public frustration over social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, emboldened electoral activists seeking to overturn results and erode trust in the democratic process.

These reverberations were felt in South Dakota, where grassroots efforts from organizations such as South Dakota Canvassing Group put pressure on state legislators to address election security through post-election audits and the banning of unmonitored drop boxes.

But the heightened scrutiny of casting and counting votes was hardly unique to the Republican-run Mount Rushmore State.

Michigan, a Democratic-controlled swing state that voted for Trump in 2016 and Biden four years later, was at the center of civil unrest before, during and after the tumultuous 2020 presidential race.

The way the two states handled the fallout – with Michigan expanding voting opportunities through ballot measures and South Dakota restricting access with legislative action – reveals disparate strategies to defend the sanctity of the vote.

South Dakota House Majority Leader Will Mortenson told News Watch that, in the case of restricting drop boxes, there were questions about the “susceptibility of abuse” and whether that justified changing the law. “Or do we have to wait until there’s actual abuse that we see before we address the susceptibility?” he asked.

David Becker, founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, which provides support and legal assistance to election workers, addressed the question by saying that ballot security measures should be based on verifiable information and not theories or speculation.

“What I’d love to see the conspiracy theorists asked is, ‘Why are you putting this out on social media? Why isn’t this being presented to a court of law?’” Becker said during the fellowship in Detroit. “Because still to this day, over 44 months since the 2020 election, there has not been one single shred of evidence presented to any court anywhere in this country that cast doubt on the outcome of that election.”

Michigan serves as testing ground for election

Trump led the vote tally in Michigan well past midnight on election night in 2020. But the race shifted in the early morning hours as nearly 3 million absentee ballots were counted, many in the Democratic stronghold of the state’s largest city, Detroit.

The logistical challenge of processing mail-in ballots on Election Day delayed results and then showed Biden taking the lead, fueling anti-government distrust from conservative groups that flared earlier in the year.

In April 2020, hundreds of protestors, some armed with rifles, stormed the state Capitol in Lansing to rail against Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s stay-at-home orders and other pandemic restrictions.

In October, a month from the 2020 election, the FBI charged a group of men with hatching a plot to kidnap the governor from her northern Michigan vacation home, with ensuing trials leading to nine convictions and five acquittals.

Following Biden’s victory, Michigan was at the center of a coordinated effort to subvert the election, with Republican activists submitting fraudulent documents claiming Trump won the state’s Electoral College vote, a prelude to the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol in Washington.

“Just about every election-denying scheme or stunt that gained national attention in the past four years was attempted at some point here in Michigan,” said Attorney General Dana Nessel, who filed forgery and other felony charges against 16 alleged false electors.

“So they really staged their dress rehearsal in Michigan because they knew it was a good laboratory for their experimentation and to probe the kind of reception they’d get on a national level.”

Ballot measure expands voter access

In June 2021, after months of investigation, a Republican-controlled Senate Oversight Committee in Michigan issued a report that found “no evidence of widespread or systematic fraud” related to the 2020 presidential election in Michigan.

But GOP lawmakers still pointed to vulnerabilities in the system and moved to pass nearly 40 bills aimed at restricting voter registration, absentee ballots, voter ID and drop boxes. Whitmer vetoed the bills and overcame a narrow Republican legislative majority, which has since shifted to a slim Democratic advantage.

In 2022, Michigan voters adopted Proposal 2, a constitutional amendment that established at least nine days of early voting, provided voters with a right to request an absentee ballot, and enshrined voter ID rules that Republicans had sought to restrict.

The measure also mandated at least one state-funded drop box for each municipality, with additional boxes for every 15,000 voters, building on absentee voting reforms passed in a similar Promote the Vote amendment in 2018.

Proposal 2, lauded by supporters as Promote the Vote II, passed with 60% of the vote, a notable mandate at a time of election-related angst in the state.

“In Michigan, you don’t get 60% of the vote with Democrats or liberals alone,” said Democratic state Sen. Jeremy Moss, who chaired the Senate Elections and Ethics Committee that implemented many of the reforms.

“That’s a coalition of Democrats, Republicans and Independents who wanted to back away from misinformation and join other states that had early voting and other provisions that provided more access to the ballot.”

Election message matches the moment

South Dakota’s own introspection on election access was accelerated by groups such as South Dakota Canvassing, whose founders were inspired by My Pillow founder and conspiracy theorist Mike Lindell’s 2021 Cyber Symposium in Sioux Falls.

Lindell, who campaigned for Trump alongside South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, claimed to have incriminating 2020 election data showing that China hacked into U.S. voting systems to help elect Biden. He offered $5 million to anyone who could prove him wrong, which did indeed happen, forcing him into a court battle as he tried to avoid honoring the bet.

“Fair elections equal a representative republic, but stolen elections equal slavery,” Canvassing Group co-founder Jessica Pollema told followers, who put county auditors and commissioners on the defensive by echoing accusations from conservative media and demanding proof of secure systems, even in a state that Trump won by 26 points in 2020.

For some Republicans, the message matched the moment. In a May 2024 poll co-sponsored by News Watch, more than 6 in 10 South Dakotans said they were dissatisfied with how democracy is working in the United States, including 32% who said they were “very dissatisfied.”

The same poll found that 58% of Republican respondents said they accepted the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

“Election denialism presents an opportunity to build a movement around restricting voting access and turning back the clock on a variety of electoral innovations,” Charles Stewart, a political science professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told News Watch in 2023.

“The places that are generally going to be the most receptive to that message are rural-based Republican states. To put it plainly, it makes sense to hunt where the ducks are.”

‘Make sure that it’s done right’

That was the political climate in which South Dakota’s Republican leadership, in consultation with county auditors, explored the issue of election security during the 2023 state legislative session in Pierre.

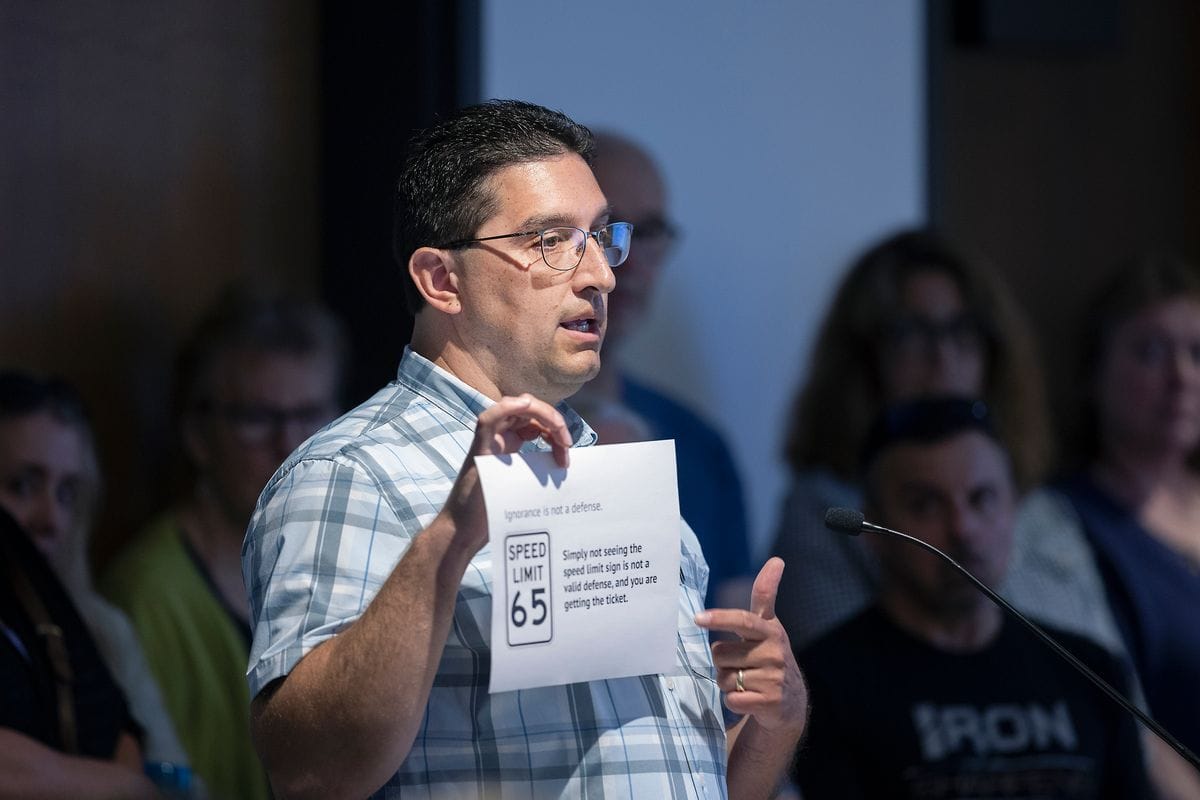

Those seeking major overhauls included Rick Weible, a computer analyst and Canvassing Group adviser who supports the hand counting of ballots and criticizes South Dakota’s 46-day early voting period, tied for longest in the nation.

“If you want to get rid of election deniers, you have to let them be part of the process,” Weible said of his lobbying efforts.

Opportunity Solutions Project, a conservative nonprofit that advocates restrictions to absentee voting, also worked with legislators and county auditors to make it “easier to vote but harder to cheat,” a mantra newly adopted by election reformists.

Some of the testimony included allegations of people dumping unauthorized ballots into drop boxes in other states, without providing proof that it happened or how it was connected to South Dakota.

The primary purpose of drop boxes is to allow absentee or early voters an opportunity to submit ballots at a time and place convenient to their schedule or circumstance. Some might use it to save postage, avoid a crowded indoor setting or merely because they’re concerned about meeting the mail-in deadline for ballots.

An Associated Press survey of election officials in each state revealed no cases of fraud, vandalism or theft involving drop boxes that could have affected the results of the 2020 election.

That didn’t mean it couldn’t impact South Dakota in future elections, said Mortenson, who along with Senate Majority Leader Casey Crabtree helped pass a package of 10 election reform bills in 2023.

“Some of the news we heard inspired legislators to kick the tires and figure out if some of the allegations seen in other states would show a vulnerability in our system,” said Mortenson.

“What we found is that we started out with a very secure, trustworthy system. The steps we took were to shore up security and acknowledge that if we’re going to have this really long early voting window, we’ve got to make sure that it’s done right.”

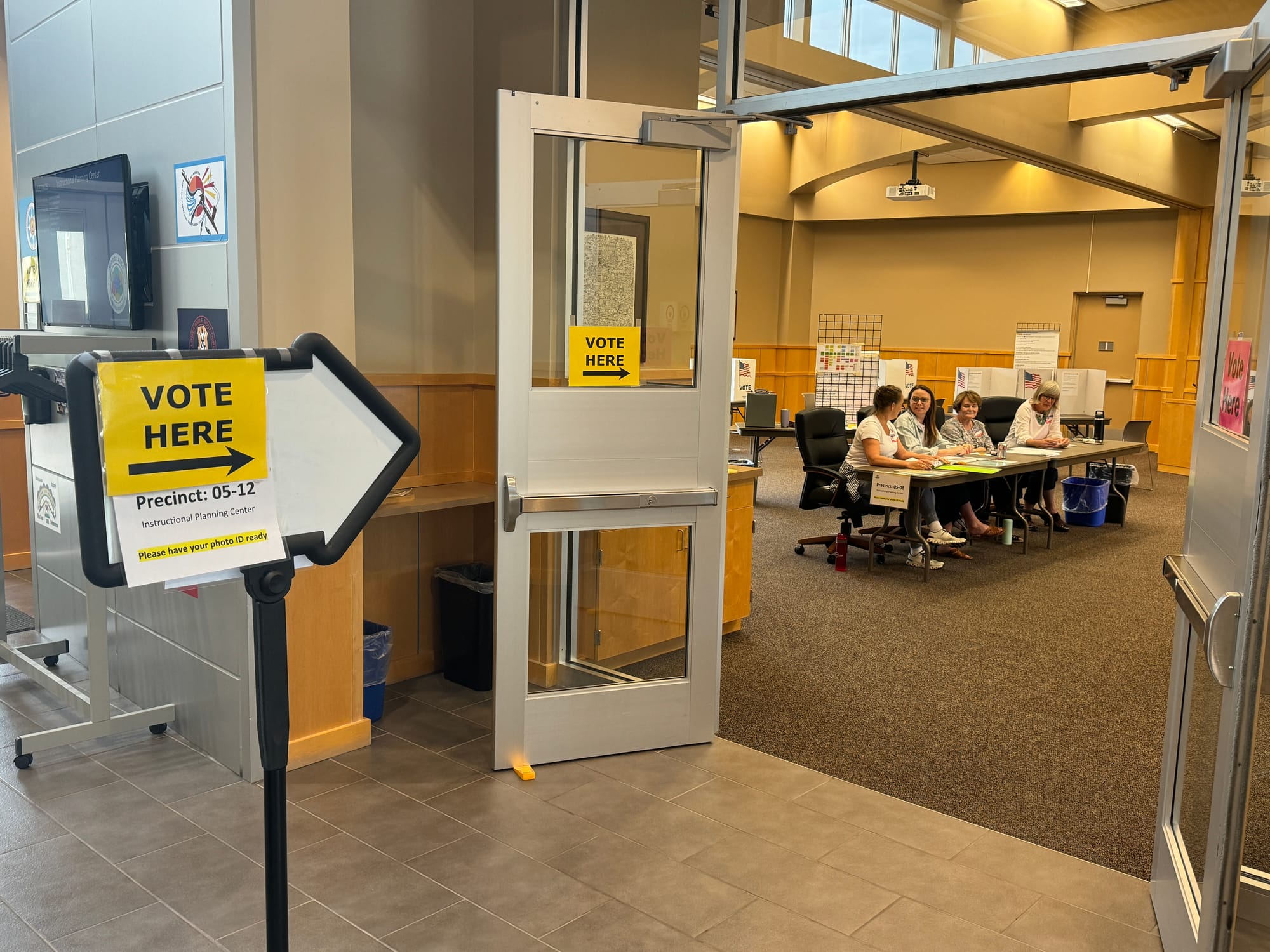

South Dakota auditors oppose drop box ban

The package included House Bill 1165, which among other measures stated that county auditors “may not establish or place … an absentee ballot drop box within the official’s jurisdiction. A completed absentee ballot may only be returned to an office of the individual in charge of the election.”

The Board of Elections approved language clarifying that to mean ballots can only be returned to the physical office of the election official, as opposed to the lobby of a county building where the office is located.

Drop boxes, used in nearly 40 states in 2020, became a target for election reformists after more than 40% of voters used the boxes to return ballots in that presidential election year, compared to about 15% in 2016, according to the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project.

A movie praised by Trump, “2000 Mules,” purported to show a pattern of Democrat-aligned ballot “mules” paid to illegally collect and drop off ballots in swing states such as Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Election experts criticized the project’s flawed cellphone tracking analysis, while Trump’s efforts to establish ballot fraud through the court system proved unsuccessful due to lack of evidence.

South Dakota did not record a single case of voter fraud or other election-related crimes tied to the use of ballot drop boxes in 2020 or 2022, according to a News Watch survey of county auditors that drew responses from 58 of 66 counties, including 29 of the top 30 by population.

“I think we’re trying to correct a problem that doesn’t exist,” said Harding County Auditor Kathy Glines, who took office in 1991 and was part of a group of auditors who testified in Pierre, South Dakota.

South Dakota election systems tested by 2004 election

South Dakota is one of at least 28 states to adopt new voting restrictions since 2020 that will be in place for this year’s presidential election, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive public policy institute focused on democracy and voting rights issues.

The overhaul was enabled partly by a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that rejected the principle of “preclearance” that had forced states to comply with federal provisions in the Voting Rights Act dealing with disenfranchisement of minorities.

Preclearance required states with a history of discriminatory voting policies to submit changes in election laws or district maps to the federal government for advance review before putting them into effect.

South Dakota was one of the states impacted because of legal conflicts involving voting rights in Indian County, specifically the counties of Oglala Lakota and Todd, which traditionally vote Democratic.

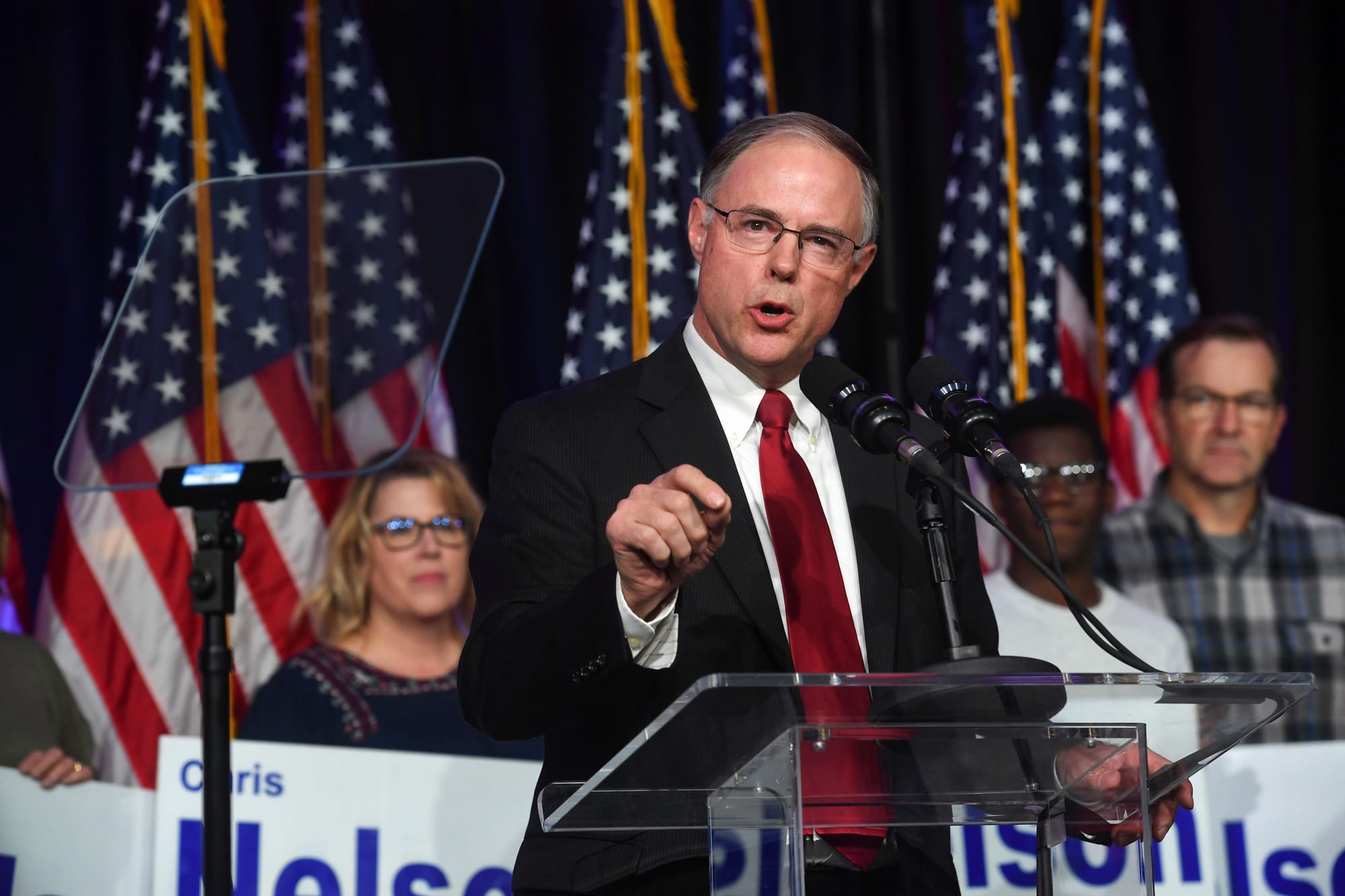

Republican Chris Nelson, who served as secretary of state from 2003 to 2011, recalled the state’s election integrity being tested during one of its most expensive and consequential elections – Republican John Thune’s U.S. Senate triumph over incumbent Democrat Tom Daschle in 2004.

The focus on Native American reservation counties stemmed from Democrat Tim Johnson’s Senate victory over Thune in 2002, when Johnson won 92% of the Oglala Lakota County vote, giving him a statewide winning margin of 524 votes when the counting ended around 9 a.m. the day after the election.

“There was a tremendous amount of stress on our county auditors for that (2004) election, particularly in Indian Country,” Nelson told News Watch. “One side was concerned about, ‘Is there going to be cheating out there?’ The other side was saying, ‘Is there going to be disenfranchisement?’ I went out and personally sat in each county auditor’s office in Indian Country and spent part of a day with each auditor to make sure that they had everything ready to go.”

Nelson added that Daschle, Democratic Senate leader at the time, sent a lawyer from Washington to sit in the secretary of state’s office in Pierre on election night to observe the process. Daschle, who lost by 4,508 votes, called Thune in the early-morning hours to concede the race, satisfied that the election was conducted fairly.

“I have a profound respect for the people of our state,” Daschle said the next day. “And I respect their decision.”

‘Make sure no one’s vote gets stolen’

On the topic of making it easier to vote and harder to cheat, Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson asked for an honest assessment of which states are truly prioritizing both aims, without regard to partisan pressures.

“Democrats are oftentimes seen as trying to increase access to the vote, and Republicans are seen as prioritizing the security of the process,” Benson said, speaking to journalists at the Detroit conference. “The best election administrators can and do accomplish both of those things at the same time.”

Mortenson pushed back on the notion that recent legislative moves in South Dakota have restricted voting access in the state.

“We have the longest early voting window in the country, so it is arguably easier to vote in South Dakota than any other state,” he told News Watch. “So in terms of the ease and convenience of voting in South Dakota, we’re at the pinnacle. But we take very seriously the idea that the person whose ballot is being counted is the person who cast that ballot. And so we want to make sure that we have a lot of accountability when ballots are cast outside of a regulated election setting to make sure that no one’s vote gets stolen.”

Nelson, currently a member of the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission, said his priority as an election administrator, despite running for office as a Republican, was to operate from a neutral perspective. That meant maintaining and sometimes expanding the rights of voters to cast their ballot in a way that worked best for them.

Some of the actions undertaken during his stint as secretary of state included taking the notarization requirement off voter registration cards and removing the “excuse requirement” that mandated certain circumstances to get an absentee ballot rather than vote on Election Day.

“The act of registering to vote and voting is an interaction between you as a citizen and your government, and we ought to be doing everything we can to make it as easy as possible for citizens to interact with the government,” Nelson said.

“When it comes to drop boxes, I was curious about where the demonstrated problem was in South Dakota because we aren’t just mailing ballots out to everybody. Each individual voter has to apply for their own absentee ballot, and that voter can decide how they want to return it. They can mail it in, they can hand-deliver it to the auditor, they can send it with somebody else to the auditor, and in places where they establish a drop box, they can put it into a drop box. The government shouldn’t be telling you which way to do it. You’ve got the right.”

Finding faith in election systems

Roebuck, the Michigan election official whose statement of fact that Biden won Michigan in 2020 drew such a strong reaction, said he felt ostracized from his party at times during the post-election tumult.

But he stuck to the task of election administration, which meant treating people’s concerns with respect and trying to share as much information as possible about how elections work.

“I think we’re at an inflection point right now where I believe my role in particular is to listen,” said Roebeck. “It’s to be honest, but it’s also to be introspective enough to say, ‘We can do better.’ Election officials are not perfect. This is not a perfect system. We should not be discrediting everything that comes at us just by virtue of the fact that someone is criticizing elections.”

Becker, whose Center for Election Innovation and Research works to build trust in voting systems, agrees that shedding as much light as possible on elections is beneficial. But the former U.S. Department of Justice attorney has little patience for claims of election fraud that are not backed by facts or data.

“There’s this myth that voter fraud is really hard to catch, so what we see must just be the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “I’m here to tell you that voter fraud is one of the easiest crimes to catch in the United States of America. You have someone who has created a document trail, who has walked up and presented themselves in front of multiple witnesses who can testify. If you tried to cast someone else’s ballot on any kind of scale, like submitting a mail-in ballot for someone else, what’s going to happen is that person’s going to try to vote. And the election officials will notice that someone tried to vote and also had a mail-in ballot. If that happened on any kind of scale, it would be identified.”

Becker added that confidence in elections is boosted by the fact that “95% of all American voters are going to vote on paper ballots this fall, including every single battleground state.”

Like in South Dakota, which uses optical scan ballots with high-speed counters, these paper ballots provide a valuable backup during recounts or audit procedures, adding integrity to the final tally.

Mortenson cites that and recent audit results as proof that “South Dakota should be proud of our elections and have a lot of faith that they are counted accurately.”

Asked about those who attack the integrity of county auditors and other election officials in the state, the Republican legislator did not mince words.

“We’ve got a message for the local officials who run elections: South Dakota has your back,” Mortenson said. “Those who cast doubt on South Dakota elections have little following and no common sense. Our auditors and poll workers should take heart and anyone who spreads lies about them should take a hike.”