Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of stories on children that Jackie Hendry, producer and host of South Dakota Public Broadcasting’s “South Dakota Focus” will write for South Dakota News Watch. Each month, she will preview the show that will air the following week.

This piece contains discussions of violence, sexual assault and suicidal thoughts. If you or someone you know is struggling, call or text 988 for 24-7 support.

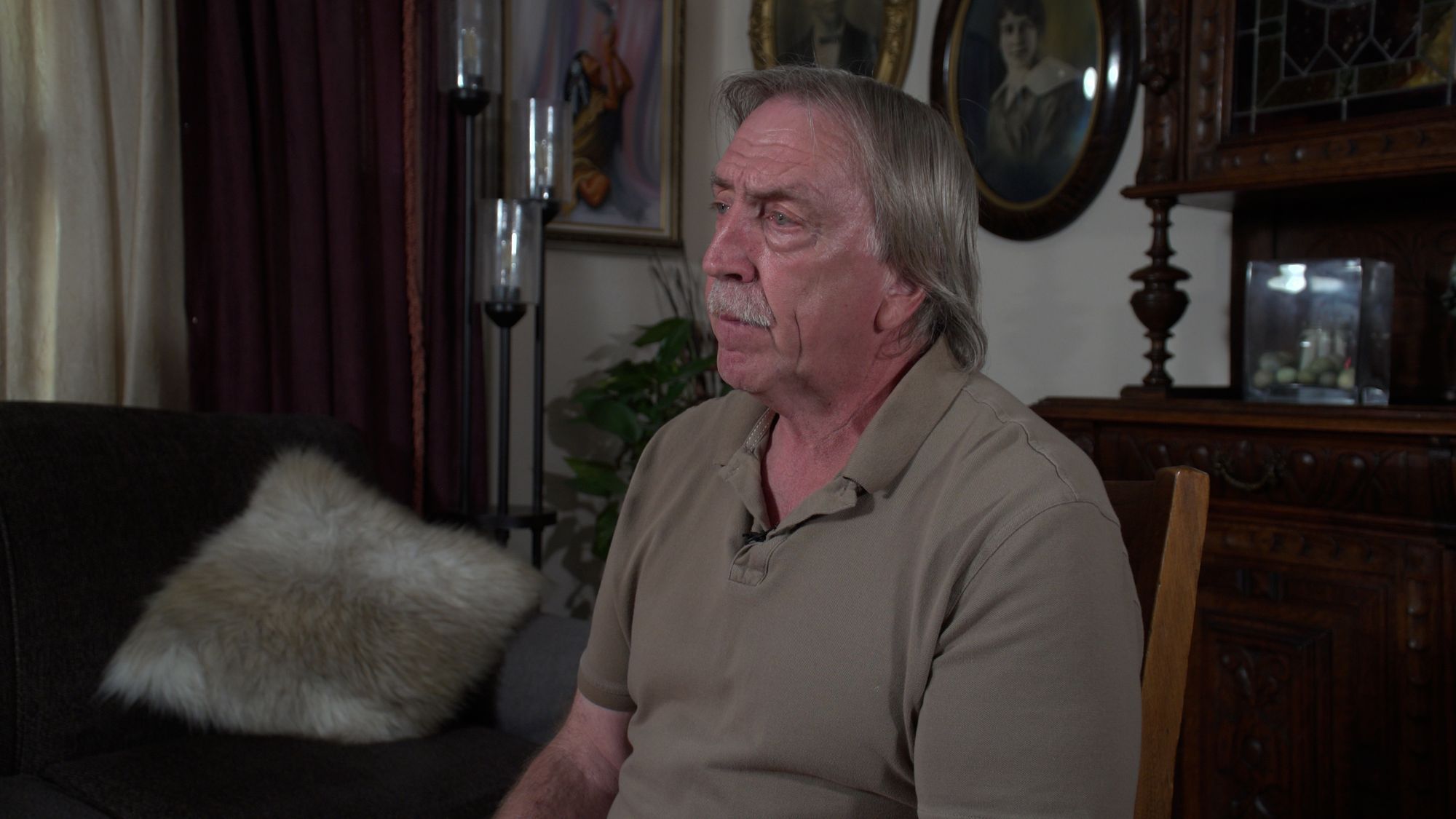

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. – Phil Hamman knew someone died. The rumors began over a November weekend in 1973. He was a sophomore at Sioux Falls Washington High School.

“We’d gotten some word in the neighborhood that some kids from our school had been killed, but we didn’t know any details,” Hamman remembered. “We thought maybe it was a car accident or something.”

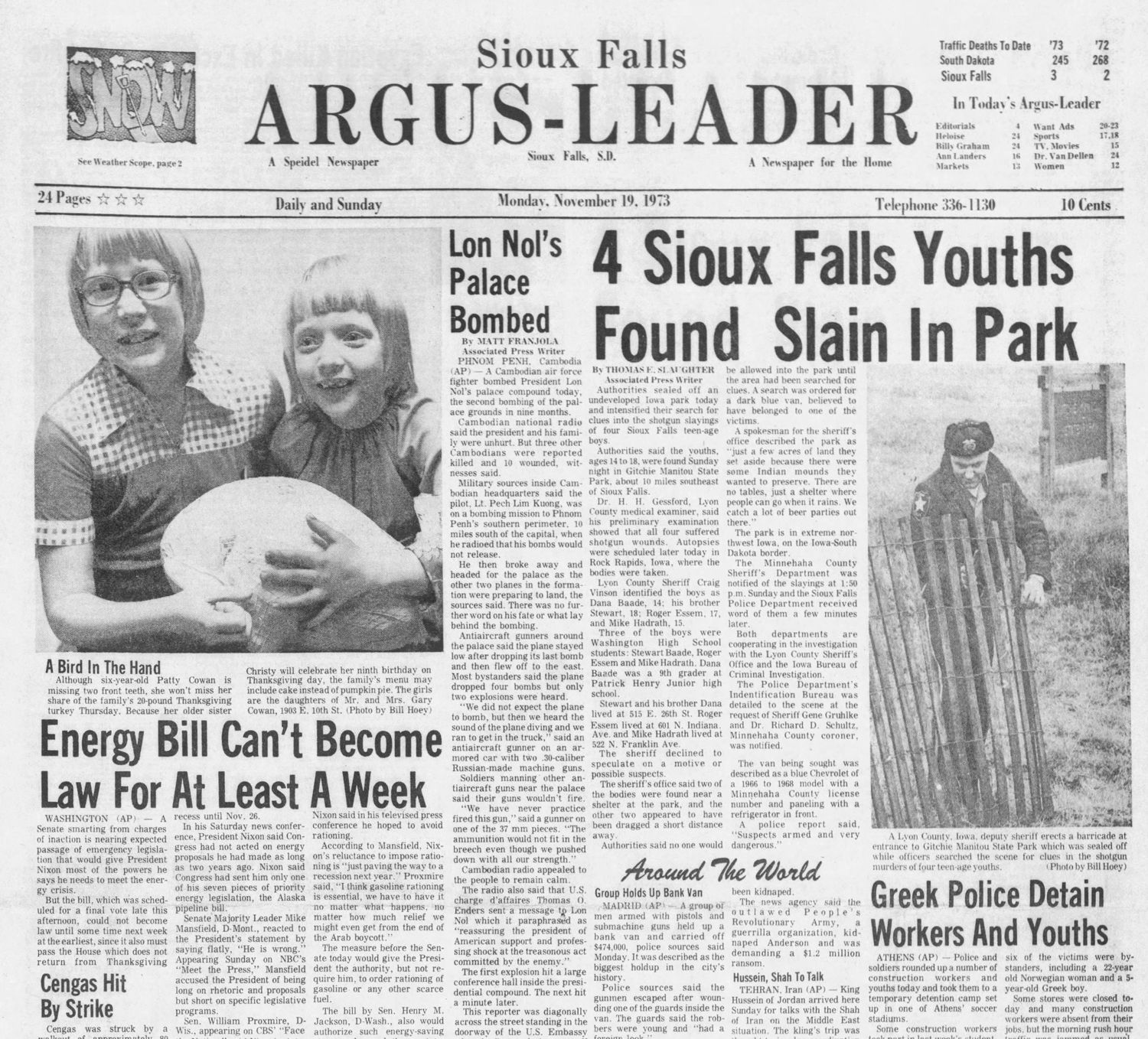

The following Monday, as he got ready for school, Hamman heard four names announced on the radio: 18-year-old Stewart Baade; his 14-year-old brother, Dana Baade; 17-year-old Roger Essem; and 15-year-old Mike Hadrath, Hamman’s childhood best friend.

“I became physically sick. I went to the bathroom and almost threw up,” Hamman said.

All four boys had been shot to death near their campsite in Gitchie Manitou State Preserve, just across the border into northwestern Iowa. A couple driving through the park found their bodies the next morning. At first, there was no suspect or motive.

Hamman went to school to find other students crying in the hallways. All, like him, were shocked and desperate to understand what happened.

“But the teachers were starting to get irritated,” Hamman said. “They were yelling at kids. ‘Don’t talk about this! Just go to class. No more talking about this Gitchie Manitou thing!'”

Hamman said he and other students obeyed without much resistance. “It’s not that the teachers were doing anything out of line. That was the philosophy in those days. You just be quiet.”

Privately, though, friends talked among themselves about who could’ve done such a terrible thing and why. When the suspects – three brothers – were captured, new questions arose. Turns out, there had been a witness: a 13-year-old girl named Sandra Cheskey.

Sandra Cheskey: The Gitchie Girl

Cheskey met Essem at a drive-in movie theater earlier that summer, and they’d been smitten with each other ever since. He’d invited her to join him and his three friends for a campfire at Gitchie Manitou the night of Nov. 17, 1973.

Three men, later identified as brothers Allen Fryer, James Fryer and David Fryer, posed as law enforcement. They shot Essem to death before taking the rest hostage. Cheskey was separated from the others, raped and threatened to silence before one of the Fryers dropped her off at her home late at night.

The next day, as rumors began spreading in Hamman’s neighborhood that some kids had been killed, Cheskey learned none of the boys made it home. She took her story to the authorities. Despite her fear and the officer’s initial doubt to her story, Cheskey played a crucial role in finding the Fryer brothers. She served as the only witness in the subsequent trial that landed each brother with a life sentence.

By age 14, Cheskey had witnessed murder, been raped and faced intense scrutiny throughout the criminal justice process. Rumors spread throughout school that she was somehow responsible for the murders. People called her the Gitchie Girl.

The social stigma remained well after the trail ended.

‘For 40 years, I walked with my head down’

Cheskey would later tell Hamman that she wished, year after year, that someone would talk to her about that night.

Family members avoided the subject, thinking it would only upset her further. Her friends didn’t talk to her anymore, pressured both by peers and parents who didn’t know what to make of the trauma she’d experienced. Cheskey eventually dropped out of school.

Decades later, she reached out to Hamman with an idea. The two had crossed paths through the years, and Hamman had written a memoir that included his memories of the Gitchie Manitou murders.

“She said, ‘I think if you want to write a book about my life and that night, I’ll open up and finally tell about it. Maybe it can help other people get through emotional things if they can read my story,'” Hamman said.

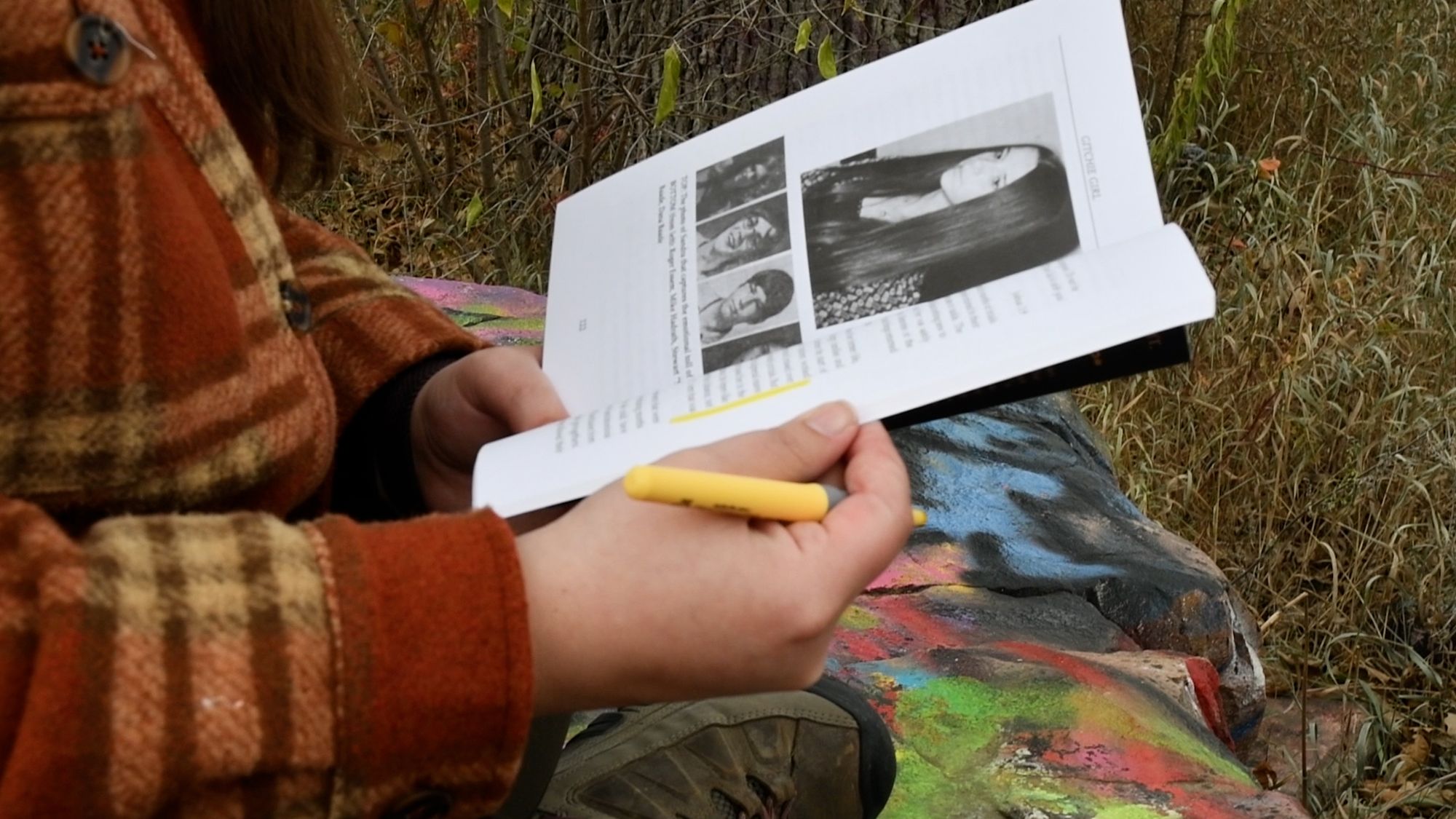

With Cheskey’s help, Hamman and his wife, Sandy Hamman, published “Gitchie Girl: The Survivor’s Inside Story of the Mass Murders That Shocked the Heartland” in 2016. The book also details Cheskey’s struggles after that fateful November night, including suicidal depression and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder that followed her for years.

The publicity that accompanied the book proved Cheskey’s instincts correct. The first chapter of 2019’s companion book, “Gitchie Girl Uncovered,” describes dozens of people at book signings shared their own stories of trauma and survival with her.

Cheskey did not respond to requests for an interview ahead of the 50-year commemoration of the murders, but Phil Hamman remembered a conversation the two had following the release of “Gitchie Girl.” During the 1974 trial, a lawyer advised young Cheskey to keep her head down so journalists posted outside the courthouse couldn’t get a good photo of her.

“And she said, ‘Phil, for 40 years I’ve walked with my head down,'” Hamman remembered. “‘Now I can finally start walking with my head up.’ So how important for her emotional state of mind to finally share that story.”

‘Children look to adults on how to respond’

Phil Hamman recently retired from 40 years as a public school teacher, mostly in Sioux City, Iowa. He’s witnessed how much things have changed since crisis struck his sophomore year.

“It’s slowly evolved from, ‘You don’t talk about this,’ to, ‘You need to talk about this.’ I’ve taught in big schools, and it seems like something tragic happens every year,” he said. “Any time (we lose a student) there’s an army of counselors that will come in and be ready to talk to teachers that are upset, and students.”

Talking through loss and trauma can mitigate mental health impacts in many cases, said Kari Oyen, director of the school psychology program at the University of South Dakota, the only school psychology program in the state.

It’s not a matter of if a crisis will touch a particular school population but when, she said.

“I think what’s so critical for adults to know is that kids look to adults on how to respond,” Oyen said. “That’s why when we see someone who’s calm in front of us telling us, ‘Here’s the things that you can do. Here’s how we are going to get through this next phase,’ that’s very comforting and actually limits the impact of stress.”

Oyen said staying silent can have the opposite effect, as Cheskey experienced.

“Adolescents are known for trying to seek rewards and approval from peers. If I’m being further socially isolated from my peers, that can make it so I’m even more vulnerable than I was before,” she said.

In Phil Hamman’s case, learning the truth of what happened the night his friend died helped him gain some closure.

“I finally got a lot of my questions answered through the research, through the court records, through the police report and through our long talks with Sandra Cheskey,” he said. “We thought maybe (the boys) were dealing drugs or something, and they weren’t. It was another one of the vicious rumors that went around.”

Rumors were all Phil Hamman had to help him process the loss in 1973. He suffered nightmares after Hadrath’s funeral.

“In those days, if you were a rich movie star or whatever, you might go see a psychiatrist if you were having emotional issues. But back then, a lot of people just kept it to themselves. I kept it inside,” he said.

‘There’s not enough help’

The philosophy surrounding responses to child trauma has certainly changed in the 50 years since the murders at Gitchie Manitou. The challenge now is providing adequate resources.

“We have a lot of kids that are going through a lot of things, and even though there’s help, there’s not enough help,” said Phil Hamman.

Schools serve as a central resource hub for most children. Oyen said 1 in 5 children today has a diagnosable mental illness, but only a quarter of those children receive any kind of treatment. “Of those who do get help, about 75% of them get help at school,” she explained.

That help can come in the form of school counselors, social workers and school psychologists. There are nationwide shortages in all three categories. South Dakota is no different, with one school psychologist available for every 1,650 students – about three times the ratio recommended by the National Association of School Psychologists.

The shortage is driven in part by the cost of the degree and the cost to school districts to maintain the position.

The University of South Dakota recently received a $3 million federal grant to address the shortage of school psychologists in the state. Oyen said the grant will include tuition stipends for school psychology students and incentives for districts to take interns from the program.

“I’m most excited because this grant, more than anything, is going to students. And we know that when we invest in students and when we invest in addressing the shortage, we know that it will have a big impact,” Oyen said.

In the meantime, a little understanding can go a long way. Phil Hamman uses his personal experience to advise other teachers.

“You have to remember the test (students) just took was on the very bottom of their priority list,” he said. “Maybe there was fighting in the home, something traumatic happened. Yes, we want them to do well on a test. Yes, we want them to do the school work, and we don’t want to let them get out of that stuff. But some days they’re not gonna be in a very good place, and you have to be ready for that.”