Stu Whitney, South Dakota News Watch

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. – Bob Zeidman has visited South Dakota just once in his lifetime. He could be $5 million richer because of it.

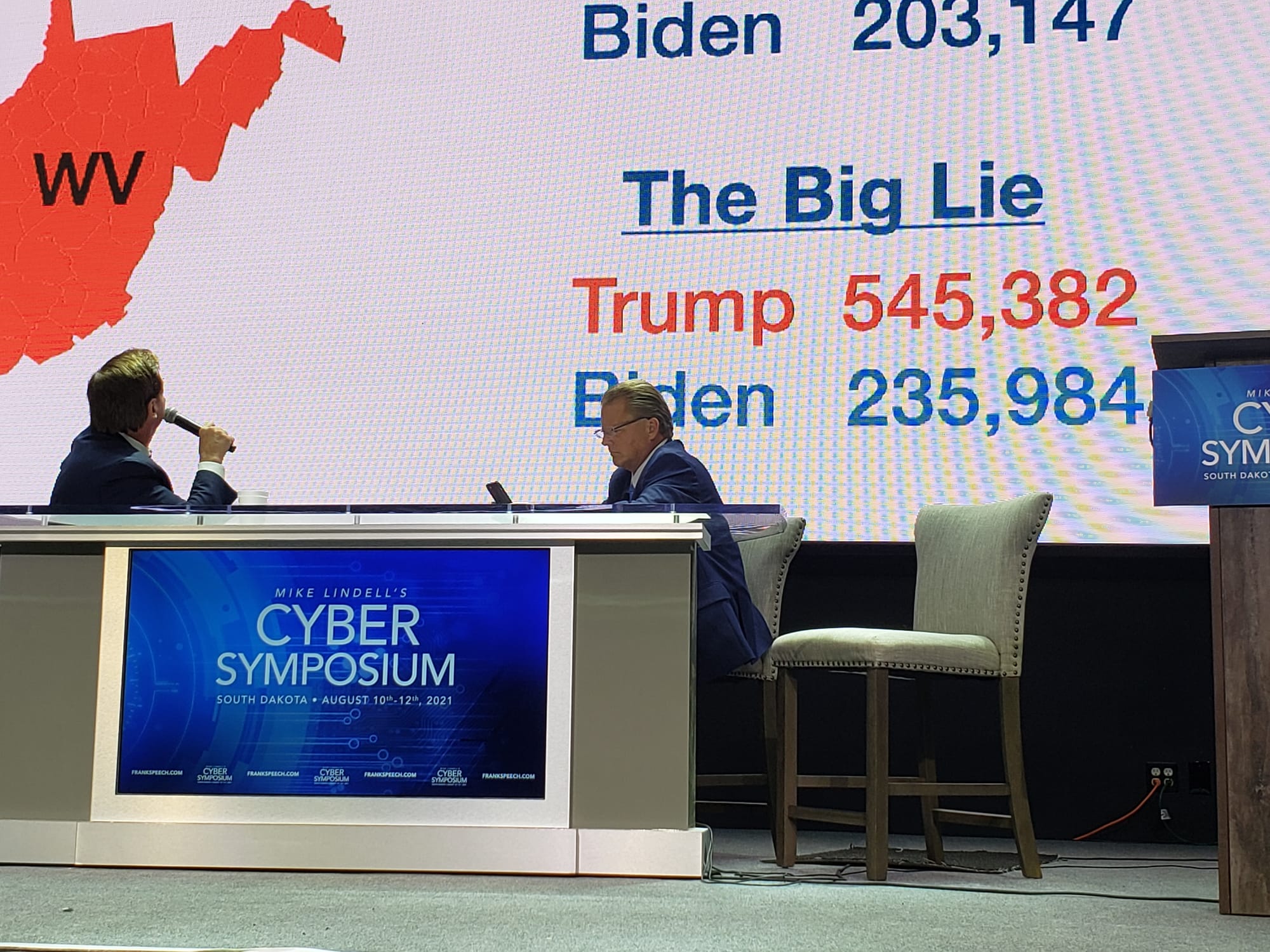

The computer forensics expert attended a Cyber Symposium in August 2021 in Sioux Falls hosted by My Pillow founder and election conspiracy theorist Mike Lindell, who claimed to have incriminating data from the 2020 presidential election. Among Lindell’s claims was that China hacked into U.S. voting systems and helped elect Joe Biden over Donald Trump.

Lindell was confident enough to launch the “Prove Mike Wrong Challenge” as part of the event at the South Dakota Military Heritage Alliance. He offered $5 million to anyone who could show that data and other materials he released were not actually from the 2020 election.

Zeidman, who specializes in software security and analysis, was skeptical soon after arriving in Sioux Falls. Lindell had promised “packet captures,” records of internet activity that purportedly showed votes being altered from Trump to Biden. But those in attendance saw nothing of the sort.

“Not only was there no packet capture data, there was no data,” Zeidman, 64, told News Watch in a phone interview from his home in Las Vegas. “There was nothing. It was gibberish. At one point I called my wife and said, ‘Start thinking about what you want to do with the $5 million.’”

Lindell vows to appeal $5 million ruling

Zeidman filed a report of his findings that was rejected by Lindell but backed up by an arbitration panel after Zeidman sued. On Feb. 21, a federal judge in Minnesota found “no evidence that the arbitration panel exceeded its authority” and ordered that Lindell pay $5 million with interest to Zeidman within 30 days.

Lindell also faces a $1.3 billion defamation lawsuit filed by Dominion Voting Systems for claiming that the company rigged the 2020 election as well as a separate lawsuit by a different voting machine company, Smartmatic.

Lindell, who could not be reached by News Watch, told The Associated Press that he plans to appeal the federal court ruling that upheld the $5 million award from the symposium.

“Of course we’re going to appeal it,” he said. “This guy doesn’t have a dime coming.”

Zeidman disputes that assessment, as do his lawyers. But the lifelong Republican, who voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020, isn’t sure what to make of his time in the spotlight, saying, “I never expected to be in this position.”

The founder of several Silicon Valley tech firms does believe election fraud exists in some forms. But he saw Lindell’s hacking claims as dangerous because they sparked outlandish conspiracy theories rather than rational discussion about election security.

“Every human endeavor has fraud,” Zeidman said. “But it’s extremely unlikely that voting machines were in any way responsible. There are too many people like me who are trained to spot hacking. Machines can have bugs that randomly throw out votes. And I’m sure that happens, and that’s scary. But if somebody were to hack the election to purposely throw it, they’d be caught. It’s that simple.”

Zeidman: ‘I realized it was all nonsense’

Lindell, a Minnesota native who overcame drug addiction and became a self-made millionaire with his infomercial-fueled pillow venture, consulted with South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem to hold his three-day cyber symposium at the Military Heritage Alliance facility, previously Badlands Pawn.

Noem campaigned for Trump alongside Lindell ahead of the 2020 election and reportedly traveled on Lindell’s private jet in May 2021 to attend the Republican Governors Association meeting in Tennessee.

The symposium in Sioux Falls was billed as invitation-only for cyber experts, politicians and media, with hotel expenses prepaid for data specialists. Lindell vowed that the election revelations would be explosive enough to reach the U.S. Supreme Court and potentially restore Trump to the White House.

Zeidman, who viewed Lindell as a rags-to-riches American success story, acknowledged being intrigued by the possibilities surrounding the event.

“My friends were saying that I should go and, you know, maybe I’d win $5 million,” Zeidman told News Watch. “I said, ‘Well, Lindell has a team of experts that already vetted the data and they think it’s correct. Now they could be wrong, but I’m not going to be able to figure that out in three days.’ But then I thought I’d be there for history in the making. Either an election would be overturned or this major figure would be exposed for misrepresenting the facts. So I thought it would be a fun experience and decided to go there. And then within three hours, I realized it was all nonsense.”

Elusive search for packet captures

Zeidman and the other experts were seeking packet capture data, or PCAPs, which Zeidman describes as “small chunks of information that are sent over a network like the Internet and then reassembled at the other end.” Lindell had promised PCAPs of votes flowing outside U.S. systems to China and coming back as votes for Biden rather than Trump.

Other specialists had the same suspicions as Zeidman.

Robert Graham, a data consultant and popular blogger on cyber issues, told Reuters that he quickly concluded that the data presented in Sioux Falls was “bunk” and “the product of a “deranged imagination.”

But Zeidman, a graduate of Cornell and Stanford who designs forensic software technology, knew that he needed to go deeper to prove the data had no connection to the 2020 election, a prerequisite for claiming the $5 million prize.

He was able to convert one of the data sets back to its origin as a Microsoft Word file containing a random series of IP addresses.

“With no other information, they were about as meaningful as a list of random words,” he wrote in “Election Hacks,” a book he self-published in November 2023. “I repeated the same process with the other text files and found even stranger stuff. These files were also word processor documents but contained thousands of lines of gibberish.”

‘Maybe this is a lost cause’

Zeidman began typing up his findings in his Sioux Falls hotel room at the Sheraton, using his experience as an expert witness in data-related court proceedings to present the evidence in ways that were difficult to refute.

There was a surreal moment when he crossed Russell Street to return to the Military Heritage Alliance on the second day of the conference, illustrating the confluence of election conspiracies and Trump’s enduring political appeal.

“There were people with signs outside the venue like ‘Honk If You Love Trump,’ and there was a woman in a bikini with an American flag,” Zeidman told News Watch. “They looked at me and said, ‘God bless you for what you’re doing.’ And I sort of thought, you might not feel that way if you knew what I was up to.”

Lindell’s team released 50 more gigabytes of data the second day, followed by another batch of 509 files. It was more of the same, Zeidman concluded, plus a spreadsheet containing generic information about internet service providers around the world, but no link to the 2020 election.

He was worried, though, that Lindell’s strategy was to provide so much data that it would become impossible to refute it all. The $5 million seemed to be slipping away.

“I started thinking, maybe this is a lost cause,” said Zeidman. “Then I got the idea to check for the dates of these new files. And it turned out that they were created or modified within a week of the symposium, which ruled out any connection to the election.”

More patriotism than data analysis

Any attempts to engage directly with Lindell regarding this information was difficult, according to Zeidman. His group passed along a note asking for more data, specifically PCAP files, but he’s not sure if the message ever got through.

“He was on stage for six to eight hours a day just talking nonstop to the audience,” said Zeidman.

On the morning of the third day, Lindell told attendees that he had been attacked the previous night near the elevator at the Sheraton by someone who asked him to pose for a photo.

“I’m OK. It hurts a little bit,” Lindell said from the stage, according to the Argus Leader. “I just want everyone to know all the evil that’s out here.”

Sioux Falls police investigated the incident but arrested no one. Lindell later claimed that he was “aggressively poked” by the person seeking a selfie.

By that point, it appeared to Zeidman and other cyber experts that what they initially perceived as a scientific data exploration had become more like a star-spangled stage production.

“There were a lot of people that were very patriotic, and I consider myself patriotic,” said Zeidman. “Lindell would have everyone recite the Pledge of Allegiance at the beginning, which I think is great. And then we’d sing ‘God Bless America’ or the national anthem. But any time he ran out of things to talk about, he’d say, ‘Let’s get up and sing the national anthem again.’ After a while, I thought, ‘OK, this is a little ridiculous.’ But people were so enthusiastic.”

Lindell: Arbitration ruling ‘disgusting’

Zeidman registered his report with the U.S. Copyright Office, put it on a flash drive and submitted it to Lindell’s team before leaving town.

Lindell never responded, so Zeidman hired lawyers and filed an arbitration lawsuit that dragged on for 18 months before a hearing was scheduled before a three-person American Arbitration Association panel in January 2023.

Zeidman said his experience as an expert witness in trials involving computer forensics helped prepare him for the four-day arbitration hearing, during which Lindell questioned his credentials and conclusions.

“I don’t know if I had an advantage or not, but I know (Lindell) had a disadvantage because he couldn’t stick to the subject,” Zeidman said. “He had to keep going on about voter fraud. At one point, his lawyer was trying to make the argument that the contest wasn’t just about packet data and that I hadn’t won the contest by merely proving there was no packet data. But they basically had to abandon that argument because when they asked Lindell what the contest was about, he said, ‘Packet data! It was all about packet data!’”

The panel ruled unanimously in Zeidman’s favor in April 2023, ordering Lindell to pay the $5 million. Lindell appealed the ruling, but the odds were against him. The legal standard for overturning an arbitration ruling requires proving that the judgment was obtained by “corruption, fraud, or undue means” or that the arbitrators showed misconduct or exceeded their powers.

In an interview with the New York Times following the decision, Lindell called the ruling “disgusting” and “mused about how (Zeidman) had been granted admission to the symposium.”

Lindell’s financial problems mount

Lindell’s lawyers tried to show in Minneapolis federal court that the arbitrators exceeded their powers by allowing Zeidman to argue that the symposium data had to include packet capture data to be connected to the 2020 election.

U.S. District Judge John Tunheim, while noting that the panel had to interpret a “poorly written contract,” agreed that Zeidman’s packet capture argument was “quite a leap” in the context of the challenge. Still, Tunheim concluded, the court’s responsibility was “not to evaluate the merits but rather ensure that the panel acted appropriately” and that narrow review led him to confirm the arbitration award.

Though Lindell immediately stated his intention to appeal, he’ll face the same hurdles at the next stage of the process. As for Lindell’s financial woes, which led him to tell CBS MoneyWatch in October 2023 that he has “$10,000 to my name,” Zeidman believes he will get his money.

“The good news is that our case is moving along much faster than that Dominion and Smartmatic cases, because those will bankrupt him for sure,” said Zeidman. “Those are for more than a billion dollars each. He doesn’t have that kind of money, but I think he can manage mine.”

‘I’m not sure that I did enough’

Though it’s easy to dismiss Lindell’s cyber symposium as failing to achieve its goals, a stance backed up by the courts, it still has political resonance.

The organizers of South Dakota Canvassing Group, a grassroots organization that questions the security of state election systems and calls for greater transparency, has cited Lindell’s event as inspiration.

Electoral activism remains prominent in South Dakota, with elected officials such as Secretary of State Monae Johnson and Minnehaha County Auditor Leah Anderson posing questions about election integrity as part of their political path.

Trump, who still claims the 2020 election was stolen, is the overwhelming favorite to win the Republican nomination in 2024, setting up a likely rematch with Biden in which ballot security will be a pervasive topic as November approaches.

So where does this leave Zeidman?

He’s a supporter of No Labels, a bipartisan organization exploring ballot options for centrist voters who reject the major-party candidates. He plans to donate some of the $5 million award to election integrity causes, including the Nevada Policy Research Institute, which describes itself as a “free-market think tank that seeks private solutions to public challenges.”

The fact that Zeidman was able to publicly debunk some of the most salacious misinformation surrounding the 2020 election has earned him some headlines. But he knows there is still much work to be done.

“Republicans will come up privately and thank me for what I did, but publicly (Lindell) is still a hero to a lot of people,” he said. “In many ways it’s a shame because he turned his life around and became a successful entrepreneur. But he’s spreading these things and people are scared to confront him because he still has a lot of power. In that respect, I’m not sure I did enough.”