MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — Tensions that had been smoldering on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota flared up 50 years ago Monday, when activists from the American Indian Movement took over the town of Wounded Knee.

In the view of the protesters, Oglala Sioux tribal chairman Dick Wilson was in cahoots with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other federal authorities, and used threats of violence to intimidate his critics. But the 71-day occupation quickly morphed into an outpouring of anger with the federal government over decades of broken treaties, the theft of ancestral lands, forced assimilation and other injustices dating back centuries.

Two Native Americans died in the fighting, and a U.S. marshal was left paralyzed.

Wounded Knee had already been seared into history as the site of an 1890 massacre by U.S. Army cavalry troops in one of the last major military operations against Native Americans on the northern plains. Accounts vary, but the massacre left around 300 Lakota dead — including children, women and older people. Congress apologized in 1990.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the occupation, The Associated Press reached out to people who were at Wounded Knee or involved from a distance to hear their stories.

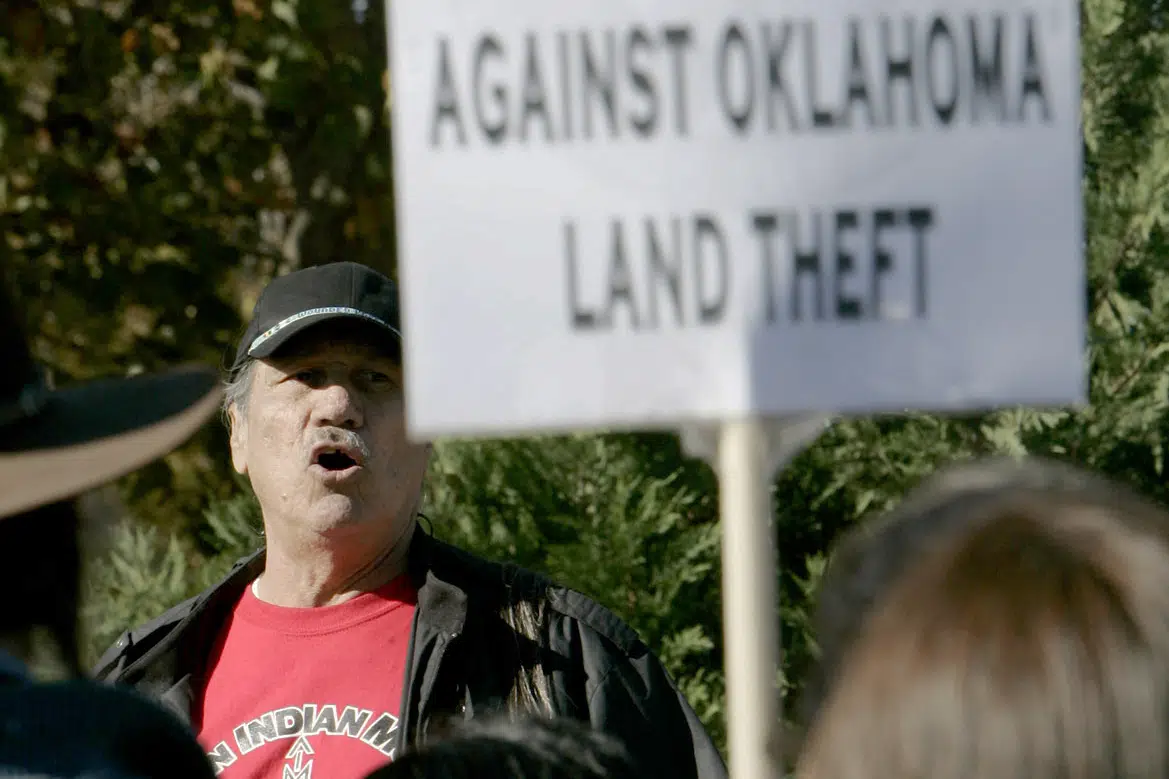

DWAIN CAMP

Dwain Camp, a member of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, was in California when his younger brother, Carter, called to say he and other leaders of the American Indian Movement took a group of activists into Wounded Knee.

“He was telling me they were in a hell of a fight,” Camp, now 85, recalled. “I heard the gunfire and that was all I needed. I went up there and stayed for the duration of the standoff.”

Their brother, Craig, a Vietnam veteran, also joined them. Camp said the rifles and shotguns the occupiers took from the trading post in town were no match for the weapons and armored vehicles the feds had.

“We were going to make it very expensive should they go ahead and roll in,” Camp said. “It didn’t come to that, thank goodness.”

Camp remembers the occupation with pride as “a very vital time” that changed his life. He said he experienced “the freest feeling that I could ever imagine.” He met AIM leaders who became famous, including Dennis Banks,Clyde Bellecourt and Russell Means. It was also a spiritual awakening for many occupiers and visitors, he said, with sweat lodge ceremonies providing a chance for prayer and learning about their traditions.

And it helped change the way Native Americans across the country saw themselves, Camp said.

“The Native people of this land after Wounded Knee, they had like a surge of new pride in being Native people,” he said.

Camp said the takeover was a catalyst for policy changes that had been “unimaginable” before, including the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, the Indian Child Welfare Act, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, to name a few. And it provided a focus for his own activism.

“After we left Wounded Knee, it became paramount that protecting Mother Earth was our foremost issue,” he said. “Since that period of time, we’ve learned that we’ve got to teach our kids our true history.”

Camp sees the fight over the Dakota Access Pipeline — which drew thousands of Indigenous people and supporters to the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota in 2016 and 2017 — as a continuation of the resurgence fueled by Wounded Knee.

“We’re not the subjugated and disenfranchised people that we were,” he said. “Wounded Knee was an important beginning of that. And because we’re a resilient people, it’s something we take a lot of pride in.”

Camp said he wished he could return to Pine Ridge for the 50th anniversary observances, but traveling isn’t easy at his age. Instead, he plans to get together with his surviving brother, Craig, who lives near him in Ponca. They’ll burn some of the sacred sage that family members bring back every year from South Dakota.

—-

JIM HUGGINS

FBI Special Agent Jim Huggins was on the other side of the roadblocks. He was one of several agents from the Denver FBI office who went to Wounded Knee to back up their colleagues.

“It was a dangerous situation,” recalled Huggins, 83, who’s retired and lives in Frankfort, Kentucky. “The people that took over the town of Wounded Knee were a group of militants, mostly out of Minneapolis. … They were dedicated members of the American Indian Movement and were very anti-FBI.”

Huggins said there was often an exchange of gunfire between the two sides.

“Every time you were out on the roadblocks, you could anticipate a shot coming your way,” he said. “You could hear them whizz by pretty close sometimes. … It seemed like every night just after sunset a few shots would ring our in our direction.”

Unlike Camp, Huggins doesn’t think much good came out of the occupation.

“I think it was totally unnecessary on their part,” he said. “I base that on interviewing several Native Americans who lived for years on the reservation. They were totally against the takeover.”

And Huggins believes the ongoing tensions between AIM and authorities led to the killings of two FBI agents in a shootout on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation two years later, one of whom was a good friend of his. AIM activist Leonard Peltier maintains he was wrongly convicted in their deaths, but successive presidents have denied requests for clemency.

—-

PHIL HOGEN

Phil Hogen was chief of staff to new U.S. Rep. James Abdnor, whose district included the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, when the occupation began just a few weeks after they moved to Washington.

“We were sort of on the front page of the Washington Post for 71 days while this was going on,” Hogen recalled. He said Abdnor “did not look kindly on that disruption. He was all for resolving differences.” But he said they worked hard to try to find a resolution, consulting with the FBI, the U.S. Marshals Service and the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Hogen, 77, who lives off the reservation in Black Hawk, South Dakota, now has mixed, but mostly negative, views on the occupation.

“It was regrettable in many respects,” he said. “That is, the disruption of government, the confrontation, the loss of lives. I don’t know that all of those wounds have yet healed. But at the end of the day there was a greater awareness of American Indian/Native American concerns and injustices they had been exposed to.”

As a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, Hogen said he could identify with some of their concerns.

“But it didn’t start out from my perspective as a national confrontation, rather a national confrontation looking for a place to happen,” he said. Tribal leader Wilson “sometimes ruled with an iron hand, but sometimes on Pine Ridge that was necessary.”

Hogen went on to serve as U.S. attorney for South Dakota under President Ronald Reagan.

If any lasting good came out of the occupation of Wounded Knee, Hogen said, it was that it “reminded the whole country about what a tragedy the original massacre was, and how those concerns or wounds were probably never appropriately addressed. It probably steered some resources toward solving some of those problems. … But it left a bad taste in the mouths of a lot of people, so it cut both ways.”

Hogen said it’s also unfortunate that relatively little has been done with the massacre site, which was mostly private land until last fall.

“It’s the site of a national tragedy, and its regrettable that it isn’t better memorialized there than it is,” he said.

—-

JIM MONE

Jim Mone had been a photographer with The Associated Press in Minneapolis for about 3 1/2 months when he was sent to cover the takeover. He packed a couple hundred pounds of equipment — including photo transmitters, a complete darkroom and a bulk pack of black-and-white film — and got on a flight to Rapid City, South Dakota.

The closest available motel room was in the town of Martin, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) east of Wounded Knee. He set up his darkroom in the bathroom and mixed his chemicals. His editor soon arrived and said, “Let’s go to Wounded Knee.”

But that wasn’t easy. The FBI and AIM had erected roadblocks. So they took backroads to get as close as they could, ditching their car about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) away, and started walking. Soon they came upon surprised AIM members who let them keep going.

“They were courteous enough to tell us how much farther we had to go,” said Mone, 79, of of the Minneapolis suburb of Bloomington.

Entering Wounded Knee, they saw a ransacked church where activists and journalists had gathered — and men with rifles. But Mone said he developed good relations with AIM leaders in the seven weeks he was there.

“They knew they needed the media, so I don’t think any media people got hurt,” he said. “You could get inches away from them, and photograph them. They treated us quite well and respectfully.”

The most worrying moments, he said, included firefights when he could see tracer bullets overhead, and a when a jet buzzed the town just a few hundred feet overhead.

To get an edge on his competition, Mone said, he practically crawled into a packed tipi where AIM activists and federal authorities smoked a peace pipe to mark the deal to end the occupation. He developed his film using equipment in his trunk before driving back to his motel, where he used a bulky transmitter connected to his room phone to send in the key picture, which Mone said was used by The New York Times the next day.

Mone said the atmosphere as the deal was signed was courteous, tense and businesslike all at once, and he believed that the fact the final negotiations were conducted in a tipi was “a sign of respect to the Native Americans.”