Joshua Haiar/South Dakota Searchlight

A company that sought to build a $3 billion carbon sequestration pipeline in South Dakota and several other states announced Friday that it’s giving up on the plan.

“Given the unpredictable nature of the regulatory and government processes involved, particularly in South Dakota and Iowa, the Company has decided to cancel its pipeline project,” said a news release from Navigator CO2.

The South Dakota Public Utilities Commission unanimously denied a permit for Navigator’s Heartland Greenway project on Sept. 6 after a hearing that lasted from July 25 to Aug. 8. The project would have gathered carbon dioxide emitted by ethanol and fertilizer plants and transported it for storage underground.

Since its permit denial in South Dakota, Navigator had asked to suspend its permitting process in Iowa and had moved to withdraw its permit application in Illinois.

Friday’s news release from the company included comments from CEO Matt Vining.

“I am proud that throughout this endeavor, our team maintained a collaborative, high integrity, and safety-first approach and we thank them for their tireless efforts,” Vining said. “We also thank all the individuals, trade associations, labor organizations, landowners, and elected officials who supported us and carbon capture in the Midwest.”

The pipeline would have crossed Republican state Rep. Karla Lems’ land near Canton. She credits the project’s demise to the people who opposed it.

“It was due to the people that rose up, the grassroots,” she said.

Dakota Rural Action was one of the groups that helped organize opponents against the project. Chase Jensen, an organizer and lobbyist for the group, called the news “a tremendous victory for the impacted citizens and landowners who were going to be crossed.”

Summit: ‘Well-positioned to add additional plants’

A similar but separate proposal from Summit Carbon Solutions to build a carbon sequestration pipeline through South Dakota and other states is still active, even though Summit’s permit application has also been denied in South Dakota. Summit has said it plans to modify its route and reapply.

Summit spokesperson Sabrina Zenor said Friday the company is “well-positioned to add additional plants and communities to our project footprint.” She said Summit remains “as committed to our project as the day we announced it.”

One of the main points of contention in both the Summit and Navigator permit applications in South Dakota was the passage of county setback ordinances, which mandate minimum distances between pipelines and existing structures and property. Summit’s filing of dozens of eminent domain cases, which the company has since withdrawn, have also been controversial. Eminent domain is a legal process to gain access to land from unwilling landowners.

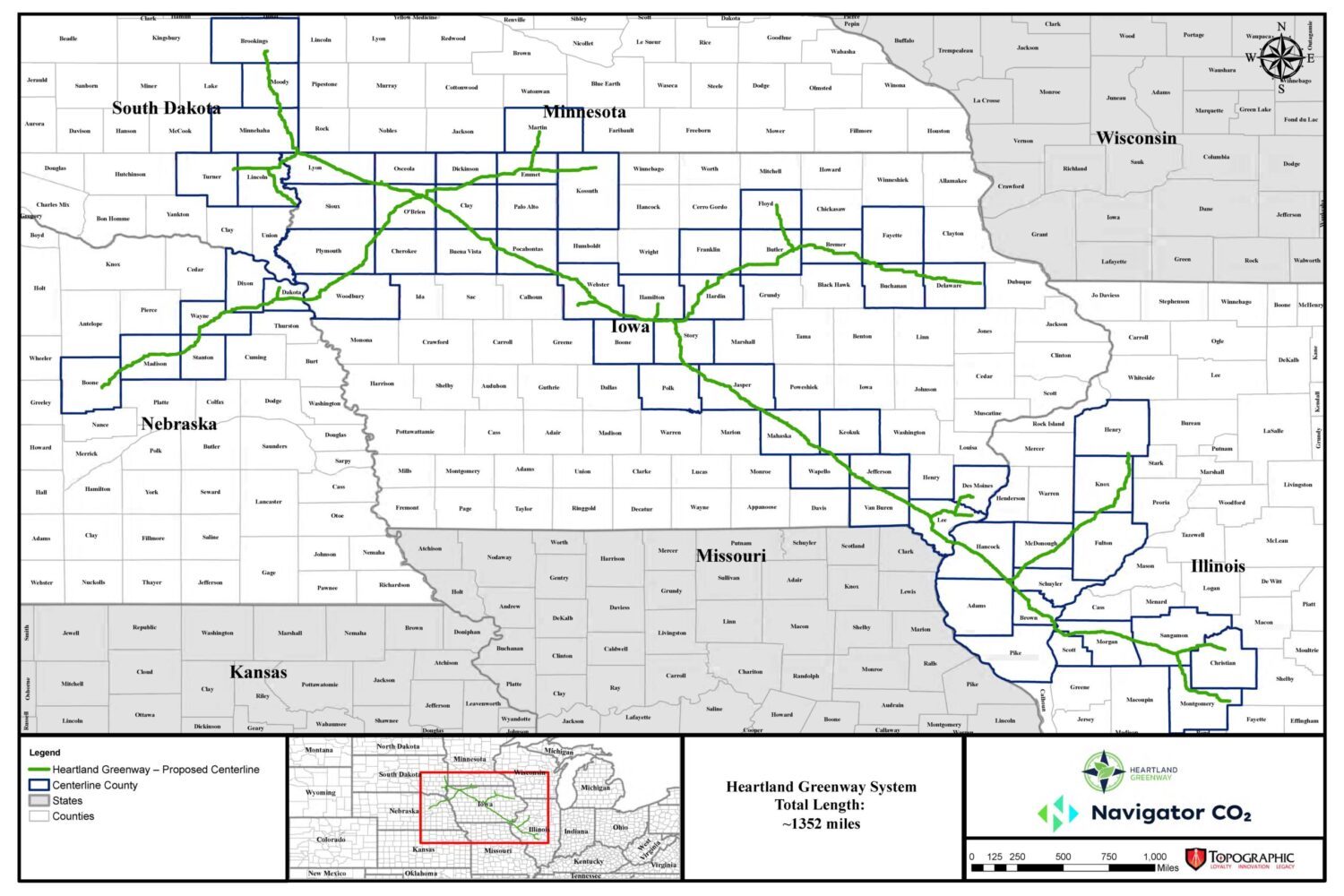

Navigator did not file any eminent domain cases. The Omaha, Nebraska-based company announced its plans in 2021, hoping to capture carbon dioxide from 21 locations — ethanol and fertilizer plants — and transport it in liquefied form via 1,300 miles of pipe to Illinois for underground sequestration.

In eastern South Dakota, Navigator’s pipeline would have covered 111.9 miles in Brookings, Moody, Minnehaha, Lincoln and Turner counties. Pipeline segments also would have stretched into Minnesota, Nebraska and Iowa.

Project backers sought to capitalize on annual federal tax credits of $85 per metric ton of sequestered carbon. The credits are intended to incentivize the removal of carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere.

Fate of easement agreements addressed

Beverly Nelson has land near Valley Springs that Navigator’s pipeline would have crossed. She’s “100% thrilled” and “delighted” by news of the project’s cancellation, but she said there’s still work to be done.

“We still need to tighten South Dakota’s eminent domain laws so we don’t continue having landowners hit with these things,” Nelson said.

Groups representing landowners announced last week that they’ve formed a coalition to push for restrictions on eminent domain. Last winter, a bill to ban eminent domain for carbon sequestration pipelines passed the state House of Representatives but was defeated in a Senate committee.

Tony Ventura, who owns land near Hudson that would have been crossed by the Navigator pipeline, hopes the Summit pipeline will be the next to get canceled.

“Nobody should have to deal with the disrespect, property damage, and harassment we have incurred,” Ventura said.

Some affected landowners and project opponents expressed concern Friday about agreements Navigator had obtained with some landowners to potentially cross private land with the pipeline.

Those agreements are called easements. But Navigator spokesperson Elizabeth Burns-Thompson said the company only ever secured options for easements, rather than actual easements.

“Which basically means those options will just expire after a few years and landowners wouldn’t have any easement on their property,” she said in a written statement.