Bart Pfankuch / South Dakota News Watch

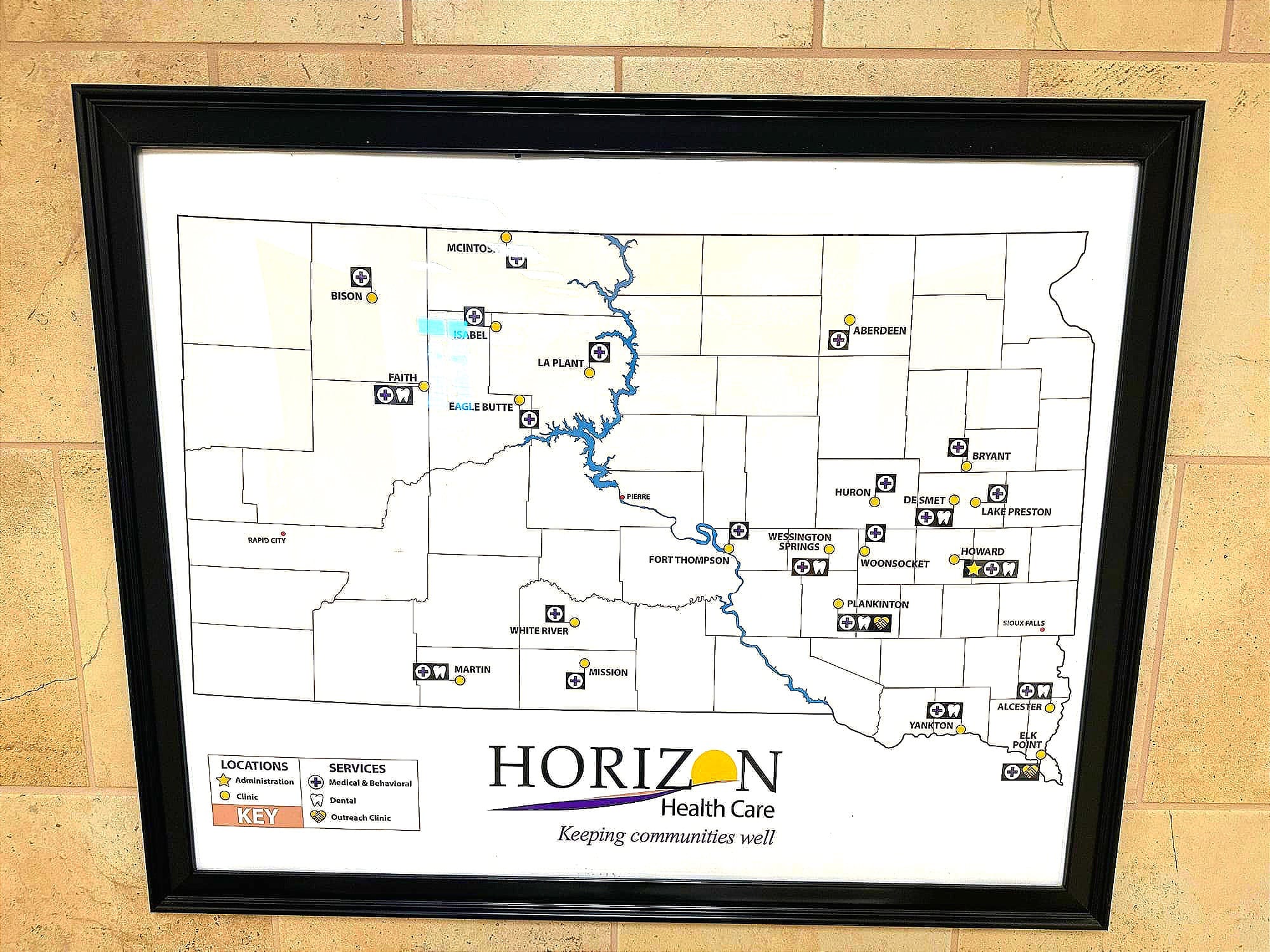

HURON, S.D. – The patchwork nature of the rural and reservation health care system in South Dakota sometimes requires compassion, innovation and a healthy dose of teamwork to keep people healthy.

While the existing health care network contains numerous barriers of access to care and troubling negative health outcomes, occasionally an “it takes a village” approach is employed to help heal those in great need.

That played out recently in Huron when an immigrant family on a work visa arrived in this east-central South Dakota city without money, insurance or English skills but full intentions of working at a local turkey processing plant. The family from Myanmar also brought their 2-year-old son who was suffering from leukemia.

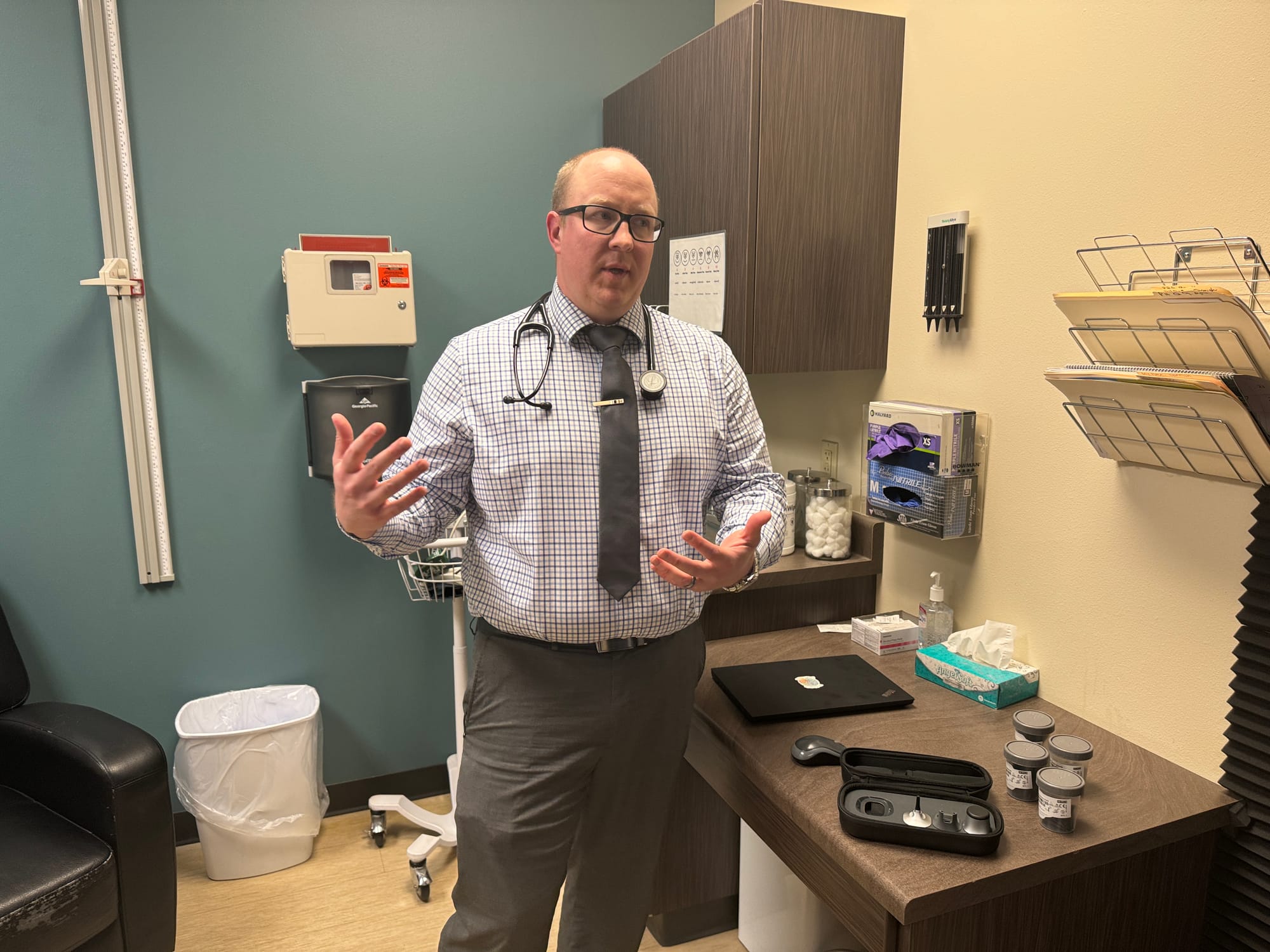

They were introduced to Leonard Wonnenberg, a physician assistant who provides primary care to patients of all incomes and backgrounds at the James Valley Community Health Center operated by Horizon Health.

Like most clinics in small cities and towns across the state, the Horizon clinic does not have specialists to provide high-level medical treatment, so outside help was a must. Furthermore, the family spoke only a Karenic language, so Wonnenberg enlisted an interpreter from a local church to help communicate then found a volunteer willing to drive the family and their sick son two hours to Sanford Children’s Specialty Clinic in Sioux Falls.

Once there, the boy received treatment and medications that have put his cancer in remission for the past couple years and allowed him to attend school as a healthy youngster.

“Now, he’s doing well. He’s thriving. He’s just like any other ordinary kid,” Wonnenberg said. “He’s really cute and he talks a lot.”

Tribal health mentor knows the ropes

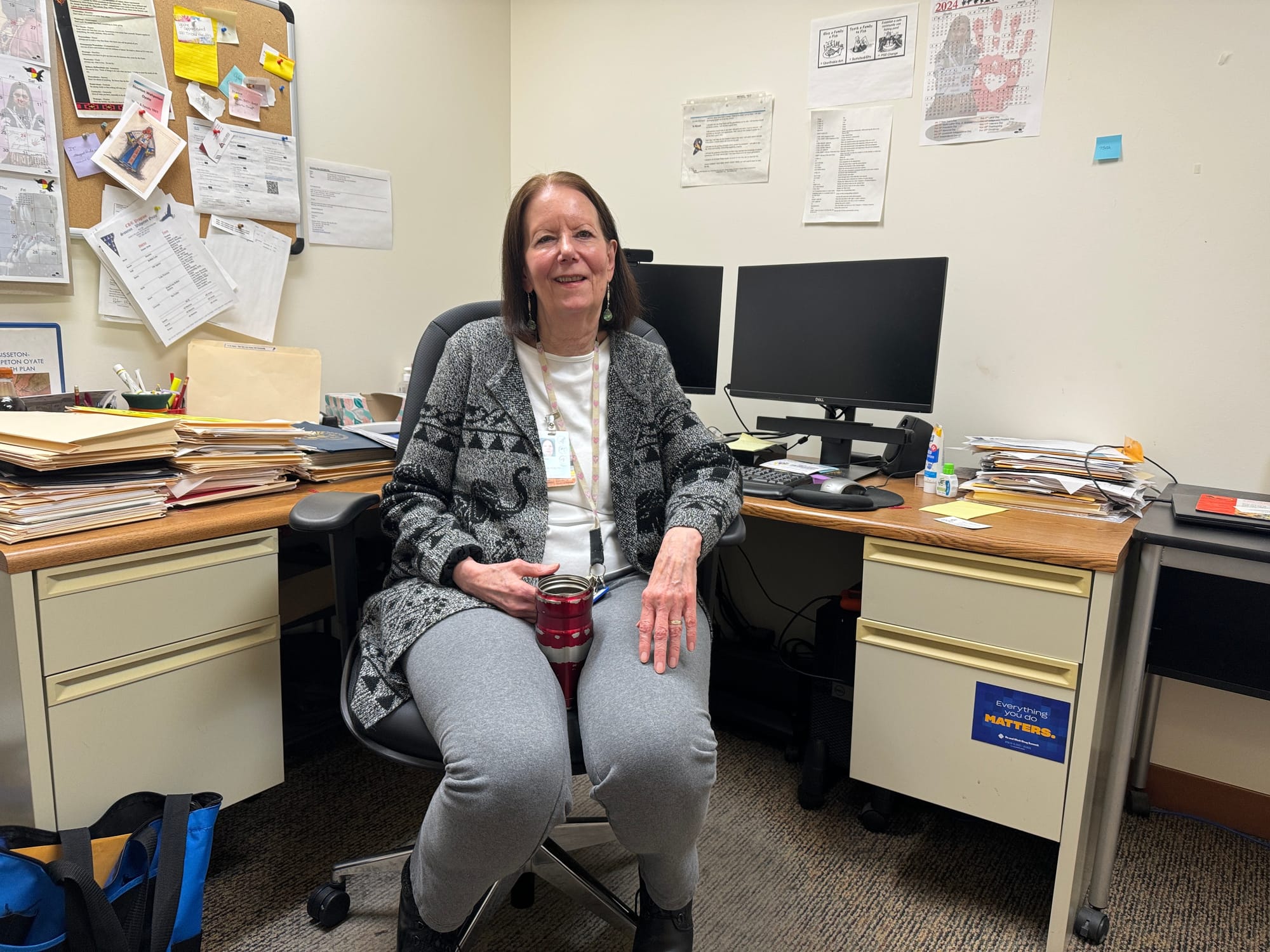

Sara DeCoteau is seen as a health care hero to many people in Sisseton and within the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate (SWO) tribe on the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation in northeast South Dakota. Several medical workers News Watch spoke to during a recent visit to Sisseton called DeCoteau their mentor.

With 50 years of tribal and public health employment on her resume and a deep knowledge of how things work — or sometimes don’t — in tribal and rural health care, it’s easy to understand why so many look up to her.

These days, DeCoteau, 70, runs the health program for the SWO tribe, and works from an office in the Indian Health Services (IHS) hospital on the east end of Sisseton.

In discussing the current state of medical care on the reservation, DeCoteau said tribal residents have ready access to a strong medical network, with a local public hospital and combined offerings of the SWO tribe and IHS.

Compared to other remote reservations in South Dakota with older facilities, including on Rosebud and Pine Ridge, DeCoteau said SWO tribal members are well served, despite a handful of chronic challenges facing indigenous health care systems.

Like almost every rural or reservation provider in South Dakota and the U.S., DeCoteau pointed to staff recruitment and retention as a major issue for SWO and IHS. She said transportation challenges, a lack of health literacy and limited service hours all create barriers to obtaining proper health care for tribal residents.

Funding shortfall a chronic issue

But no local issue can top the challenges created by the chronic underfunding of IHS and other government tribal health programs. In a July 2022 report from the Office of Health Policy within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the initial bullet point in the report confirms this.

“There are long standing and persistent health and health care disparities among American Indians and Alaska Natives, which are a result of centuries of structural discrimination, forced relocation, reduced economic opportunities, and chronic underfunding of health care for this population,” the report states.

DeCoteau said tribal residents of South Dakota, thanks to treaties signed with the federal government generations ago, are generally able to access medical care without insurance or a payment if they use IHS or tribal facilities.

But for services not offered, tribal members can obtain treatment outside the reservation through a “purchased-referred care” payment system, in which the federal government pays non-tribal providers for services.

While that system is working well now in Sisseton, DeCoteau said, there have been times where the referral funding has run out near the end of the fiscal year each summer.

“For years and years we used to say ‘don’t get sick after June’ because funding would evaporate by then, and only the highest priority cases would be considered for care,” she said. “It is so aggravating, so unfair to the American Indian people to be treated like that.”

IHS: Public health, partnerships needed

In response to emailed questions from News Watch, the Indian Health Service Office of Public Affairs acknowledged the significant barriers to obtaining medical care on reservations. The office listed transportation challenges, a lack of access to specialist care and a need for greater preventative care as hurdles.

“Specialists are often hundreds of miles from patients’ homes (and) many people don’t have the financial means to get to appointments, or they have family obligations (caring for children, etc.) so can’t get to appointments,” the office wrote in an email response.

The rural health system needs more nurses and community outreach workers, IHS said, adding that when urgent help is needed, many reservation residents rely on underfunded emergency service providers.

“EMS funding is insufficient for the needs in our communities, given the large span of reservation boundaries and the time it takes to transport patients to cities,” the office wrote.

Mobile health vans and public health prevention programs, including greater testing and treatment amid an ongoing syphilis outbreak in Indian Country, can also help prevent major medical conditions, IHS said.

As for potential solutions, IHS said telehealth has been effective in creating access to rural care, and that more partnerships are needed between IHS, the state of South Dakota, and medical colleges to share information and resources.

“Incorporating traditional healing into our clinics. Working with tribal partners to incentive preventive care. Working with state of South Dakota to take advantage of novel programs to improve access to care in rural communities,” the office wrote.

Creative ways to fill the gaps

DeCoteau and other members of her team at SWO are willing to go the extra mile, and be extremely patient and diligent, to find new ways to serve the local population.

In late 2023, after a two-year effort, the tribe started its Asniyapi Field Health Clinic program in which a nurse practitioner travels the region in a mobile clinic to provide a wide range of medical, behavioral health, addiction, education and pharmacy services to people in their communities and neighborhoods.

To develop the mobile clinic program, DeCoteau and others combined a U.S. Department of Agriculture rural development grant with funding from IHS and money from the federal American Rescue Plan Act to buy a large van and equip it with technology, diagnostics and a nurse practitioner.

In recent weeks, the mobile clinic has helped diabetes patients manage their weight and wounds, it offered Suboxone treatment for people with opioid addiction and provided physicals to children who need one to qualify for Head Start programming.

“Now, we’re able to provide medicine without walls and take health care to the people in our communities,” she said.

Personal experiences reveal gaps

DeCoteau has her own telling experiences navigating the rural health care system in South Dakota.

A friend recently drove 160 miles to an appointment in Sioux Falls but had to turn right around because her provider was unable to keep the appointment.

A while back, DeCoteau needed cataract surgery on both eyes, so her sister traveled from Minnesota to drive Decoteau two hours to Sioux Falls for the two-day procedure, costing money for gas and a hotel stay. When complications arose months later, DeCoteau had to arrange for transportation to Sioux Falls again, but a blizzard required her to travel a day early and pay for more fuel and several nights in a hotel.

“That’s rural health care,” she said. “You’re at the mercy of the system and the weather too.”

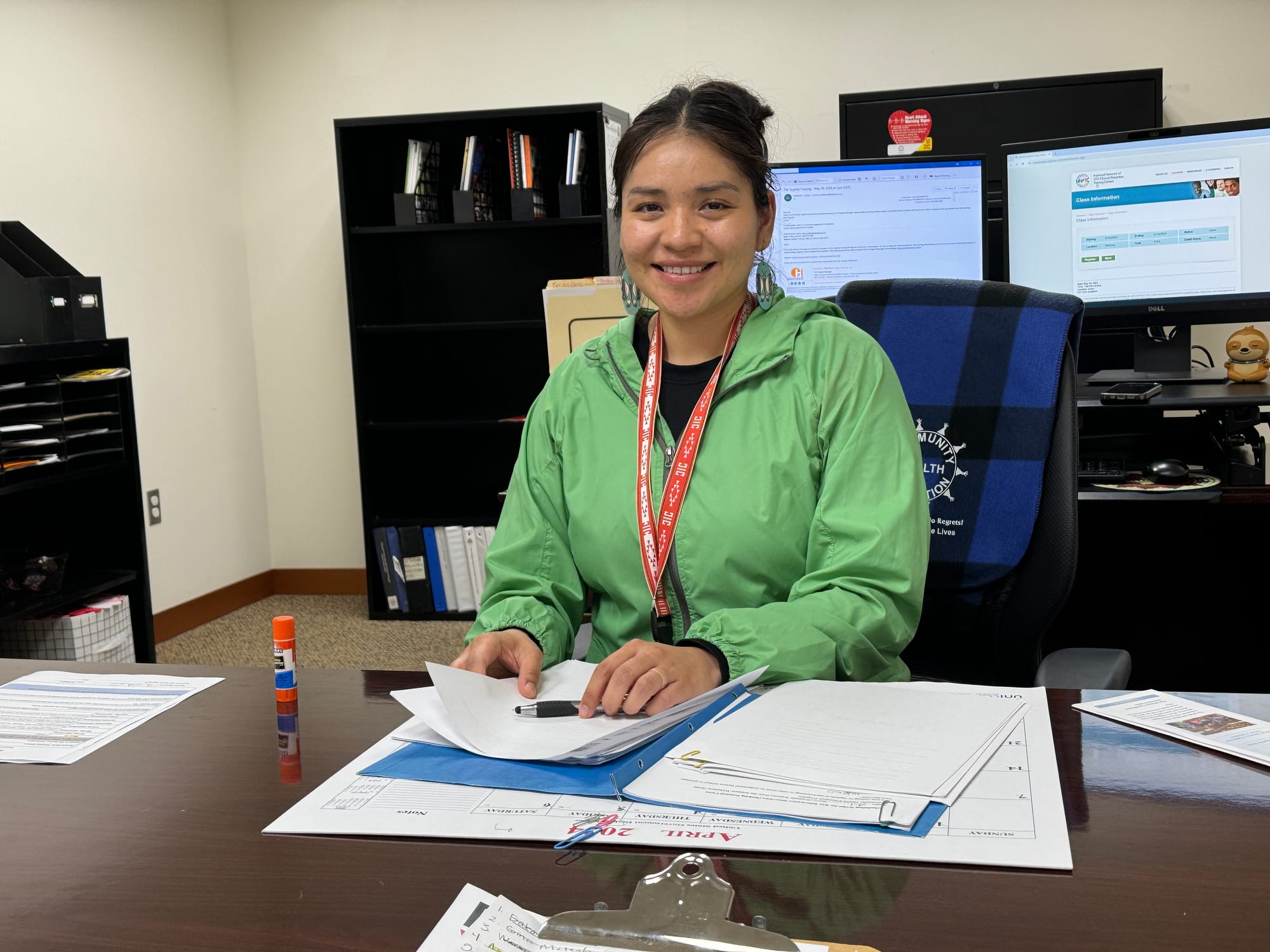

Wahleah Watson, who works in tribal health education in Sisseton, said she decided to drive an hour to Watertown to give birth last year due to concerns that birthing services at the local public hospital were inadequate.

“I heard from relatives that they had a bad experience, and I didn’t want to go through that,” she said.

Watson said she received prenatal services through IHS and then made the drive to Watertown, hoping she had planned well and did not undergo any last-minute complications. When the Coteau des Prairies Health Care System in Sisseton ended its child delivery program on March 1, Watson said all pregnant women in the area will now be forced to make that drive for a hospital delivery.

“That’s a huge barrier to our young mothers, and in general, it’s scary to get pregnant because we don’t have that medical facility here to give that care and deliver babies here,” she said.

Counseling services not meeting the need

People who need behavioral health or substance abuse treatment and counseling have options to get help in rural areas, but access is limited or can be difficult to obtain for some.

The American Psychiatric Association recently labeled South Dakota as one of the worst “mental health care deserts” in the country, with nearly half of all counties not having a single behavioral health provider.

The expansion of telehealth services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic has helped open doors to behavioral health for more people. But poverty and geographic isolation prevent some people, especially those on reservations, from having computers or access to the internet.

Richard Bird, director of the Dakotah Pride Center operated by the SWO tribe, said the facility offers both inpatient and outpatient treatment services to tribal and non-tribal patients, but it’s limited in its ability to accept new clients due to space and funding limitations.

The inpatient facility has 12 beds but could easily fill double that number at any time with people who need services, Bird said. And the program’s sober living halfway house that accepts former prison inmates and others in transition is insufficient to meet the need, he said.

“We could always use more bed space, and our halfway house could be expanded to meet the need,” Bird said.

Bird said the program makes accommodations to help people get to the facility, including sending transport buses as far as Sioux Falls to pick up patients who qualify. But like many other health programs in reservation areas, the facility suffers from stagnant financing from the Indian Health Services, which contracts for services with the Pride Center.

“Costs have gone up, but the funding remains the same,” he said. “We do what we can because it’s a difficult population to work with, but we’re making some progress.”

Rural hospital ‘does what it can’ within limits

Craig Kantos has spent decades in health care administration, often in small towns or rural areas, so he is well positioned to manage the many challenges that come with being CEO of the Coteau des Prairies health system.

The small hospital has a medical staff of eight, with a general surgeon, three physicians and four mid-level providers handling family medicine, emergency care and respiratory and physical therapy treatment. It has a lab, X-ray, MRI and CT scan machines, telehealth stations and a helipad for emergency transports.

Kantos said the hospital continually struggles to hire new medical staff when openings arise. The hospital could accommodate three more family physicians and five or six additional nurses if it were able to recruit them. But finding quality, affordable local housing is a big barrier for potential new hires, he added.

Even with current staffing, Coteau des Prairies is able to stabilize patients in emergency situations and can then transport or refer patients with conditions in more serious categories of cardiology, orthopedics, major fractures and now OB/GYN conditions to hospitals in Sioux Falls, Watertown or Fargo, North Dakota.

Kantos said the hospital system faces regular challenges in balancing revenues and costs, especially since 70% of gross revenues come from sources that do not cover the full cost of treatment such as Medicaid, Medicare and IHS.

Still, Kantos is confident that his staff and facility are well-equipped to provide quality primary care and handle most health care emergencies that arise. The hospital was recently named a Top 20 quality critical access hospital in the nation by the National Rural Healthcare Association.

“You do the best with what you have. But the staff here, they will bust their butts to save a life,” he said.

Kantos said he and hospital leadership meet regularly with other health providers in the area, including the leadership of the local IHS and tribal medical facilities, to maintain cooperation and share critical information about the local health care landscape.

Since March 1, when the hospital stopped delivering babies, Kantos said his remaining medical staff has undergone regular training in order to make an emergency delivery if needed.

“If we cannot safely transfer you, we have to deliver you,” he said. “But that being said, if you have a baby that’s not in the correct position, we have to figure out how to get you out of here quickly.”

Like providers across rural South Dakota, Coteau des Prairies offers primary and preventative care options but is aware that some people are unwilling or unable to take advantage of services offered, Kantos said.

“You can get access to preventive care here, and you can for sure get it if you want it,” he said. “It’s not that we don’t provide it, it’s that the patients don’t think they need it or they don’t necessarily come for one reason or another.”

‘If we aren’t here … conditions can worsen’

With a caring demeanor, a commitment to helping others and a family history of living and working with minority populations, Wonnenburg might be the perfect person to work in family medicine in a place like Huron.

He comes from a family of health care workers and educators who have spent much of their careers working on American Indian reservations in the state.

Huron is a small city in east-central South Dakota with a population of 14,000 that includes people from a wide diversity of backgrounds. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Huron, which is home to a huge turkey processing plant and a strong manufacturing base, has 2,600 Hispanics, 2,000 Asians and 1,300 other non-white residents. Many speak no English or English as a second language. The median household income in 2022 was $57,700, about $12,000 less than the state average.

In the lobby of the Horizon Health clinic where he works, a sign greets patients with the word “welcome” translated into more than a dozen other languages. In his time in Huron, Wonnenberg has become adept at using resources within and outside the clinic to provide health care to people from other cultures and ethnicities, those without insurance or money, patients who have no access to transportation and those whose cases require more care than is available at the Horizon clinic.

“Some of these folks, they would rather spend their last $10 on groceries for their families rather than $10 on medicine for their health, for treating something as simple as strep throat,” Wonnenberg said. “But you know, a strep throat if left untreated, it can lead to things like rheumatic fever, which can be very devastating.”

A sense of compassion on the part of medical workers in rural settings, he said, can go a long way to breaking down patient barriers to health care, especially for a diverse patient population in Huron where some people may come from a place of distrust.

“One of the things that drives people here is the amount of compassion that we have for our patients, and they really see the helping hand in our care,” he said. “Then they tell other people about it, and word of mouth goes a long way.”

Wonnenberg worries that systemic barriers to getting health care in rural areas that surround Huron will prevent some people from being healthy and may lead to increased mortality.

“These are people that have moms, these are people that have dads, these are people who have kids, and so we want them to be successful in their communities,” he said. “So we need to treat these people like human beings.”

‘Figure out that jigsaw puzzle’

The nursing shortage and lack of desire of health workers to move to rural areas are tops among his concerns, and he hopes incentive programs can be created to lure more providers to small towns and reservations.

Wonnenberg would like to see higher reimbursement rates to providers from Medicaid and Medicare to help offset rising costs. He said he supports expansion of Medicaid in South Dakota, which has allowed more low-income people obtain preventative medical care.

Wonnenberg said pharmacists can also play a larger role in providing not just medicines but working more closely with local practitioners to create a holistic approach to patient care.

And he sees an even larger role for telehealth to connect rural patients with specialists in larger cities. He recalled one recent case where a patient on a work visa had kidney disease that caused 30 pounds of excess fluid to form on his body. The man had very little money and no insurance and was referred to Wonnenerg through a local church that also helped with interpretation.

Wonnenberg used telehealth services to connect the patient with specialists who helped stabilize him and later, an insurance navigator helped the man obtain government insurance.

“You’ve got to figure out that jigsaw puzzle to get people treated,” he said.

But new challenges still pop up regularly to providing health care in small towns and rural areas, Wonnenberg said.

For instance, a state program that helped pay for community health workers is ending, which could reduce contacts and home visits between patients and providers. Some of those patients are likely to forgo preventive care that would prevent conditions from worsening and could force some patients without insurance into medical bankruptcy, he said.

Wonnenberg, who soon will leave the James Valley clinic to pursue a speciality in orthopedics, said his time working in Huron has solidified his belief in the critical role rural clinics and health care workers provide across South Dakota.

“It’s a safety net because if we aren’t here, conditions can worsen and get out of control and it can end badly for patients,” he said. “We’re always trying to bridge barriers, to bridge gaps, to ensure the best outcomes for patients and their families — and their communities.”