(Bart Pfankuch/South Dakota News Watch)

WALL, S.D. – The small, somewhat worn meat processing plant in rural Wall seems an unlikely place for the birth of a new trend in South Dakota agriculture. But it could fundamentally change the economic landscape for the state’s $1 billion annual beef cattle industry.

The 2,400 square-foot Wall Meat Processing plant is the current home base of an aggressive, innovative new ownership team that has plans to revolutionize how South Dakota ranchers get their animals processed and expand opportunities for local consumers to buy meat raised almost in their own backyards.

On a recent day, a half-dozen or so workers were on task in the cramped but clean meat plant that sits less than a mile from Wall Drug. It’s the last structure standing before the city of 700 fades into a nearly endless prairie to the north.

Built nearly 60 years ago, the boxy white plant takes in local cattle as well as a few hogs, sheep and buffalo and processes them from live animals to carcasses to final cuts of meat packaged in plastic, ready for consumer purchase. With a capacity of only 15 head of cattle per week, the plant hardly makes a dent in processing the roughly 1.5 million beef cows raised in South Dakota in 2022, the overwhelming majority of which are trucked out of state for processing.

But the two co-owners of the plant, who bought it in 2017 after the former owners shuttered the business for several months, are using what they have learned in Wall to develop a business expansion plan that agricultural leaders said could form the model for future development of a new generation of in-state regional meat processing plants.

The local packing plants, they said, will allow more livestock grown in South Dakota to be processed, sold and consumed entirely within the boundaries of the Rushmore State. Local processing will create jobs and tax revenues, save ranchers money on trucking and packaging and create a fully South Dakota farm-to-table process that is increasingly popular among consumers.

Local beef, local stores, local consumers

The Wall owners and a third partner recently launched a new entity, I-90 Meats, which plans to build a $21 million, 30,000 square-foot meat processing plant in New Underwood, a town of 600 people located south of Interstate 90 midway between Wall and Rapid City.

The high-tech plant would have capacity to process 15 cattle a day, or about 4,000 a year, and would include a retail market, agri-tourism learning center and culinary demonstration area.

The plant, with a proposed groundbreaking in early 2024 and projected opening in 2025, could employ as many as 50 people with wages up to $36 an hour, according to I-90 Meats co-owner Ken Charfauros. The plant will process beef, pork, lamb and bison produced by local ranchers. It would sell those products at the plant store as well as a retail location in Rapid City and at other groceries across the West River region.

“South Dakota is fourth or fifth in cattle production in the nation, but we sell our cattle out of state and then buy it back, so it’s kind of backwards,” said Charfaurous, who co-owns Wall Meat Processing with Janet Neihaus. The third partner in the new I-90 Meats venture is Thomas Fitch.

“To keep the regional protein production and the revenue right here, it helps our community. And not just the ranchers and the processors but also the consumers,” he said.

Change should help farmers, state coffers and consumers

The move toward greater in-state processing will mark a major shift from the existing method most South Dakota livestock producers use to get their animals processed.

Under the current system, most animals, cattle in particular, are raised in the state but then trucked out of state for finishing, slaughtering, processing and packaging at one of the four major meat packing companies in the U.S.: Cargill, JBS, National Meat Packing and Tyson.

None has a plant in South Dakota.

By sending animals to those plants, producers pay much more to have their animals transported and processed, and the state loses out on the resulting jobs and tax revenues generated by the plants. Meanwhile, consumers then pay more for products that are returned to the state for sale and for which they have no idea whether the meat they are eating was raised in South Dakota, California or even Mexico or Brazil.

U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds, R-South Dakota, said further expansion of processing capabilities of agricultural products in South Dakota would be a win for both producers and consumers.

“We want to make sure our meat is high quality. … And when you’ve got quality local producers and processing is done locally, you’re going to get a higher price for it (the products),” Rounds said in an interview with News Watch.

Latest of several other efforts

Since the 1990s, he said, the state has seen a variety of efforts to expand processing, from the opening of the Hutterite-owned poultry plant in Aberdeen to development of soybean biofuel plants to improvements and expansions at the Smithfield Foods pork plant in Sioux Falls.

But Rounds said long-range infrastructure and telecommunication challenges as well as difficulty in finding capital and labor to fuel development of processing plants have limited the growth of large meat processing plants in South Dakota.

He has worked in Congress to end “the stranglehold” the four major processors have on the American beef market, in which they process about 85% of the beef raised in the U.S.

As livestock processing evolves, and consumers seek a greater connection to how and where their food is raised, Rounds said he sees the growth of smaller processing plants around the state as a likely path forward for the agricultural industry.

“Our smaller towns still struggle, and at the same time, this is the place that feeds the rest of the world,” Rounds said. “If our premises are correct, that people want to buy American beef because of its quality, then I think these smaller processors are going to continue to grow and I think they’re going to become the wave of the future.”

Rounds said government can play a role in encouraging growth in processing capacity by providing one-time, startup financial incentives while adding more flexibility in labeling and marketing rules to create opportunities for growth in smaller, regionally based processing operations in South Dakota.

I-90 Meats, for example, received a $3.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to get its operation started and has a USDA guaranteed loan package of $21 million, Charfauros said. Another proposed new regional plant in Faulkton received a $2.2 million USDA grant this year.

Rounds said South Dakota farmers and ranchers who produce high-quality foods will get higher prices for their products if they are raised, grown and processed locally. Consumers will benefit by having greater access to the quality foods that are produced in their own communities or nearby, particularly beef products that are almost exclusively processed in other states.

“We want to continue to provide alternatives other than the four major processors who process not just American beef but a lot of foreign beef as well,” Rounds said. “Anything we can do to make sure that Americans who want to buy high quality American beef are able to do so, the better off we’re going to be.”

Food processing on the rise in South Dakota

The ongoing evolution of the meat packing industry in South Dakota is part of a larger statewide trend in which more agricultural products that are grown or raised in the state are being processed here, despite a pair of what many in the ag industry saw as notable setbacks.

Last year, a $500 million Wholestone Farms pork plant in Sioux Falls and a $1 billion Western Legacy Development beef processing plant in Rapid City both fizzled.

And yet, the increase in processing facilities statewide continues, a trend that typically opens the door to stronger markets and opportunities for new growth or expansion among producers who must fill the need created by larger processing capacity.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in the South Dakota soybean and corn industries, in which producers are seeing new local markets materialize for their products.

Ground was broken in September for a $500 million soybean processing plant near Mitchell that as early as 2025 will produce soybean meal for animal feed and soybean oil used in biofuels. Meanwhile, the company Gevo plans a $1 billion plant near Lake Preston that as soon as 2025 will process corn into biofuel for use in jets.

News Watch has also reported recently on the dramatic expansion of the cheesemaking industry in South Dakota, where new or expanded plants in Milbank (Valley Queen Cheese), Lake Norden (Agropur cheese) and in Brookings (Bel Brands) have facilitated an increase in milk production in the state.

According to the USDA, South Dakota dairy farmers produced 4.2 billion pounds of milk in 2022, up from 3.1 billion pounds in 2020 and 2 billion pounds in 2013. The milk produced in South Dakota in 2022 was valued at $1.1 billion, according to USDA.

One ongoing proposal would build an $86 million, 12,500-head dairy operation on 250 acres of land now owned by the brothers of Gov. Kristi Noem. While the proposed dairy near Hazel faces some local opposition, backers including Noem’s brother, Rock Arnold, said the project would create new revenue and higher prices for farmers who raise grain and generate a new source of fertilizer for surrounding farms.

The beef cattle industry in South Dakota has fluctuated but has remained fairly stable over the past several years. According to USDA, the state produced 1.6 million head in 2015, 1.8 million in 2019 and 1.5 million this year.

The number of permitted large cattle feedlots, known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOS, has fallen in South Dakota over the past four years, according to the state Department of Agricultural and Natural Resources. In 2019, about 564,000 cattle were held on 166 permitted CAFOS, and in 2023, about 532,000 cattle were held at 149 CAFOs.

The federal and state governments are trying to aid in the expansion of meat processing plants across the country.

In 2021, the Noem administration offered about $5 million in COVID-era federal funding in grants to meat processing facilities across the state, much of it to existing small meat plants and butcher shops that expanded, though a few new facilities did receive funding.

Congress that same year allocated about $1 billion in American Rescue Act funding through the “Butcher Block Act” to expand meat processing capacity across the country, though South Dakota processors received only about $32 million of that funding.

Greater innovation needed in South Dakota

Scott VanderWal, president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau Federation, said the state has historically been slow to expand its processing capacity in a number of agricultural fields.

Shipping products out of state for processing drives up costs for producers and eventually consumers. It also has led South Dakota to miss out on potential employment and tax revenue opportunities that come with greater processing plant capacity and development.

“More local processing has been something we’ve needed for a long long time because for whatever reason, we’ve been happy in South Dakota just to produce things — corn, soybean, cattle and hogs — and ship them out of state for processing,” Vanderwal said. “It all comes down to producing and processing the food in our own country and doing it ourselves versus exporting that work and then importing the products back.”

Vanderwal said South Dakota farmers are starting to take steps to use technologies such as robotic milking, inventive financing packages and precision agricultural using computers and satellites to expand processing capacity in the state.

“We haven’t been innovative enough in South Dakota to find ways to process our products, and instead we’ve been content to carry our products further down the line,” he said. “As long as we stay innovative, with new ideas and ways of trying new things, we’ll have a lot of opportunities and the future of agriculture will be bright because we have to continue to feed our people across the country and across the world.”

A return to ranching’s past

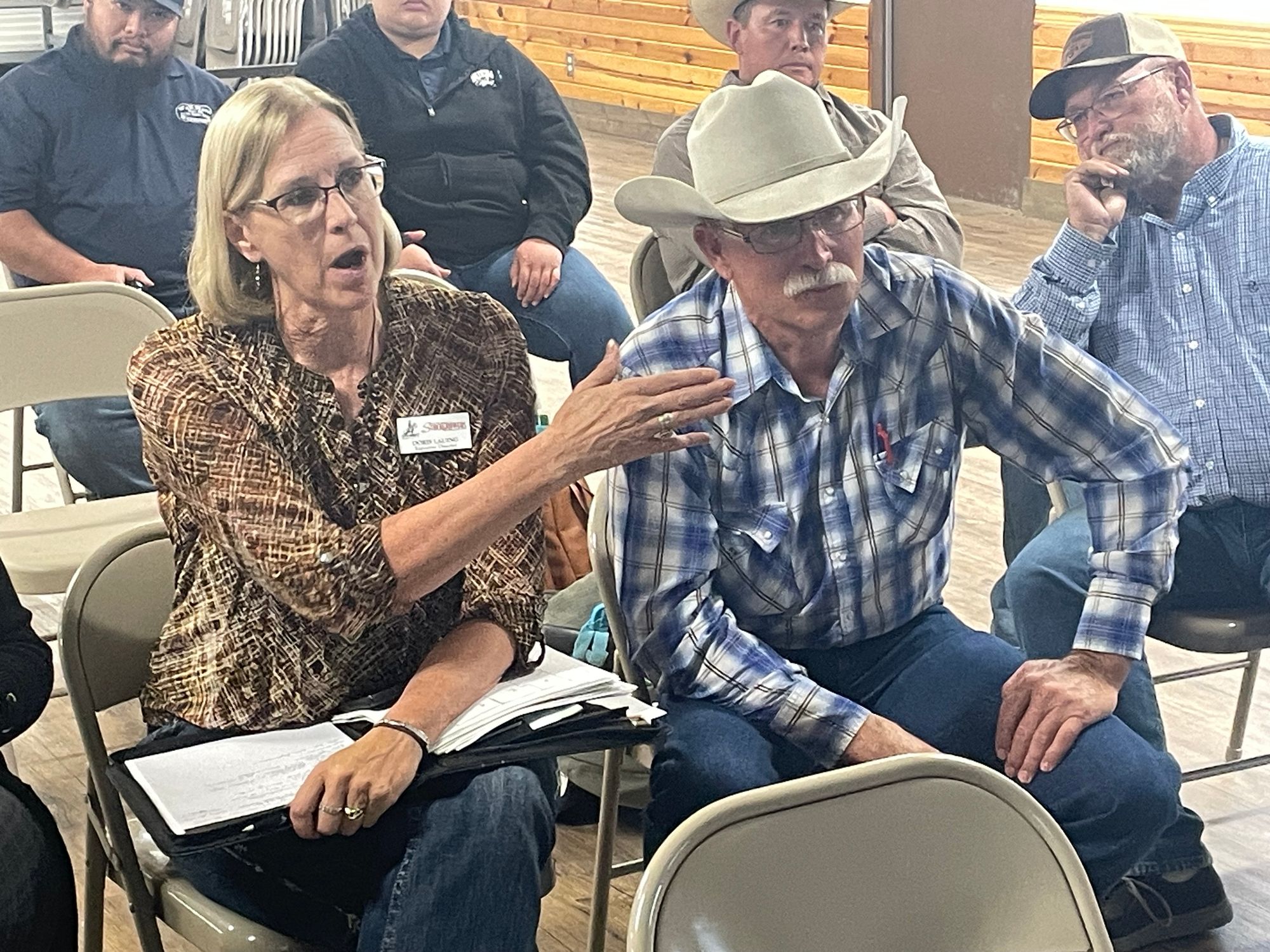

Doris Lauing, executive director of the South Dakota Stockgrower’s Association, said the move to expand processing capacity in South Dakota is in some ways a return to the past, when South Dakota producers worked on a smaller scale and were able to have their livestock processed and sold in their local communities.

“This is how the Stockgrower’s Association started in 1893,” she said. “So, if you can give us an end product right here, hallelujah 100%, because you’re going to benefit the entire agricultural community.”

Lauing said there is a great need for more meat processing facilities in South Dakota to reduce costs for producers and allow more revenue for ranchers and retailers to remain local.

“This is something that rural America needs because we have to be able to bring our product somewhere other than shipping it down to the big packers” Lauing said at an Oct. 21 public meeting on the proposed I-90 Meats plant in New Underwood. “Let someone buy it here and keep that money local.”

Lauing said she attended the October meeting to show strong support for completion of the New Underwood plant. She said consumers will benefit by knowing that the meat they buy in a store was raised and processed by their neighbors and not by someone unknown who is hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

“When you walk into a market, you’ll know where your steak comes from when you buy it,” said Lauing, who is also a rancher in Sturgis. “You can say it’s produced in South Dakota, and it’s not produced in Brazil, it’s not produced in China, it’s from right here.”

Charfaurous also noted that developing more regional capacity for livestock processing in South Dakota and across the U.S. will strengthen the nation’s ability to protect the security of its food production system in a crisis and not be subject to the whims of the international food production system.

During the height of the COVID-19 epidemic, for example, major beef plants closed due to illness outbreaks, which interrupted the supply chain and processing capabilities, resulting in financial hardship for South Dakota cattle producers.

“There needs to be more plants built,” Charforous said. “When those plants closed, what did it do to food security in the nation? It went crazy.”

Vanderwal added that development of regional processing facilities will strengthen the U.S. food production system overall, which will protect the American food supply from outside competition and potentially unsafe processing methods elsewhere.

“I’ve been saying for years that we don’t want our food system to become vulnerable to the same gyrations as our energy system is now,” Vanderwal said. “We have a lot better food safety rules and more control over how things are done.”

A nearly 5-year process to plant opening

Innovation, along with a major investment of time and money, are the keys to making new meat processing ventures successful, Ken Charfauros said. The process of designing, planning and gaining approval for the New Underwood meat plant has taken more than three years already and will extend to five years before becoming operational.

Once up and running, the owners have big plans to do more than just process meat. They have agreements to expand butcher and animal science training opportunities with South Dakota State University and Western Dakota Technical College. They are selling their meat processed in Wall in a large retail store they opened in Rapid City and even in Big D gas stations in the Black Hills region.

Word of their expansion has gotten out and recently caught the ear of Laura Moser, who with her husband hopes to open a bed-and-breakfast inn at New Underwood next year.

Moser recently toured the Wall Meat Processing plant and had many questions about the processing methods and final products produced. Her hope is to serve her guests foods, including meats, that are raised and process locally as a way to differentiate her inn and support a growing farm-to-table movement.

“If you can go right from producer to plate, that’s huge,” Moser said. “We’re trying to keep it all local for our guests.”

Before the I-90 Meats partners even break ground in New Underwood, their big plans have raised interest among at least one other South Dakota ranch family that hopes to build a smaller, yet similarly focused plant in northeastern South Dakota.

Investing in family, and in the beef industry

Troy Hadrick is part of a five-generation family legacy of farming and ranching in South Dakota. He and his family want to expand their business and provide another regional meat processing option for ranchers in northeastern South Dakota.

The family’s plan is to build a $13.5 million meat plant, called North Prairie Butchery, that could process 25 head of cattle per day near their hometown of Faulkton, a city of about 830 people in Faulk County located an hour southwest of Aberdeen.

Hadrick has qualified for a $2.2 million grant from the USDA to get the project started, though the money only comes in the form of a reimbursement for investments already made into the plant, he said. He is trying to arrange financing for the project but has had little luck with lenders in South Dakota, which he called “disappointing.”

Hadrick and his wife, a native of Sturgis, have three children, a son studying agriculture at South Dakota State University and two daughters still in high school. They hope to break ground on the meat plant in 2024 and have it open for business in 2025.

Hadrick said the plan to build a processing plant in Faulkton arose from a desire to strengthen the family business but also due to three difficult years in a row in trying to get their cattle processed out of state, first due to a 2019 fire at a Kansas processing plant, then due to COVID-19 plant shutdowns in 2020 and finally from complications in how packers were buying cattle.

“We own the cattle from conception to harvest, and then we lose all control, so you cross your fingers that it will work out in the end,” he said. “It’s one of the things that came out of COVID, when we found out we have some holes in the system, and when you have a lot of your eggs in one basket, and something happens to that basket, we see some pretty big ripples form that are hard to overcome.”

Two years ago, the Hadricks made a deal to provide beef to the Vanguard Hospitality group of restaurants in Sioux Falls, which includes Morrie’s Steakhouse, Minerva’s, Grill 26 and Paramount Cocktails and Food. After a successful trial period, the family now sells about 60 to 70 carcasses of beef weighing about 800 pounds each to the restaurant group in a year, Hadrick said.

When the first shipment of beef was made to Vanguard, Hadrick took his two daughters out of school and brought them on the trip to Sioux Falls to drop off the beef himself.

“We pulled up to the back door of the restaurant and unloaded the beef, and it was like a light bulb came on for our girls, that this is why we do all the work we do at home,” he recalled. “They finally saw the end product, and it was pretty exciting and meant so much to them.”

Lack of processing holding ranchers back

The overall lack of meat processing capacity, especially federally inspected processing plants in South Dakota, puts a hardship on his business and those of other ranchers, Hadrick said.

According to the USDA, South Dakota has 38 state-inspected butcher shops, though most are very small and cannot begin to serve the needs of large beef producers. The state trails several neighboring states in the number of federally inspected meat plants, which provide producers with greater options on regard to selling their meats in other states.

A USDA database shows that South Dakota has 33 federally inspected livestock processing plants, though only nine handle beef and pork and five are considered “very small” by USDA standards. Meanwhile, Minnesota has 172 federally inspected processing plants, Iowa has 151 and Nebraska has 109.

At this time, Hadrick must drive three or four head of cattle at a time either 200 miles or 250 miles round trip to USDA-inspected processing plants to get them processed on a custom basis, which allows him to make sure the cattle he provides the butcher are the source of the meat he receives back and sends to the restaurants.

“We don’t have much capacity in South Dakota to process cattle on a custom basis,” he said. “We’re capped because we’ve got X amount of capacity in the state and it’s just not very much.”

Like the owners of I-90 Meats, whom Hadrick has spoken with several times as he plans his construction project, he hopes to expand opportunities for ranchers like himself to showcase the high-quality animals they raise and give consumers an option to buy meat that has a known origin and a closer connection to the connection to the communities where they live.

Hadrick likens the idea to what California wine producers have done for decades in promoting the specific region where their grapes were grown and then labeling products so consumers know more about what they getting, where it came from and who produced it.

“I think there’s an opportunity to do that with our beef,” he said. “We know we’ve got a good product, so why don’t we highlight that?”