Seth Tupper, South Dakota Searchlight

Bill Walsh picked up a ringing phone in Deadwood during the fall of 1983 and heard Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s voice.

“Bill, I’m off the wagon,” Kennedy said, according to Walsh. “I’ve got a flight coming in tomorrow.”

The two had become friends in 1980. Kennedy campaigned in South Dakota that year for his uncle, U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy, who ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Walsh and RFK Jr. were fellow Irish-Catholic Democrats, and Walsh was a former priest with experience counseling addicted people. He knew about Kennedy’s struggles and had offered to quietly help him seek treatment.

Things didn’t go according to plan.

Drugs in his luggage

Passengers on Kennedy’s flight to Rapid City saw that he was high. The flight crew radioed ahead to authorities, who let Kennedy go but obtained a search warrant and found heroin in his luggage.

Scott McGregor was a deputy prosecutor in the local state’s attorney’s office. He said it wasn’t difficult to find Kennedy, given the widespread knowledge of Walsh’s political connections.

“I got the notion that, well, why would a Kennedy be coming out here anyway?” McGregor recalled. “And it crossed my mind it had to be to go see Bill Walsh.”

Kennedy was charged with felony drug possession, and the story made national news.

Rod Lefholz was the local state’s attorney at the time. As a Democrat — the last one elected to a Pennington County office, as far as he knows — he faced the task of prosecuting a member of the nation’s most famous Democratic family.

Lefholz approached the case like any other and said it proceeded normally, other than the presence of national media such as People magazine in the courtroom and letters that arrived by the dozens from people with opinions on the case.

“Some of them wanted me to hang him from a lamppost,” Lefholz recalled, “and others said, ‘Why do you keep picking on the Kennedy family?’”

In the end, Kennedy pleaded guilty and avoided prison based on a number of conditions, including two years of probation and the completion of addiction treatment.

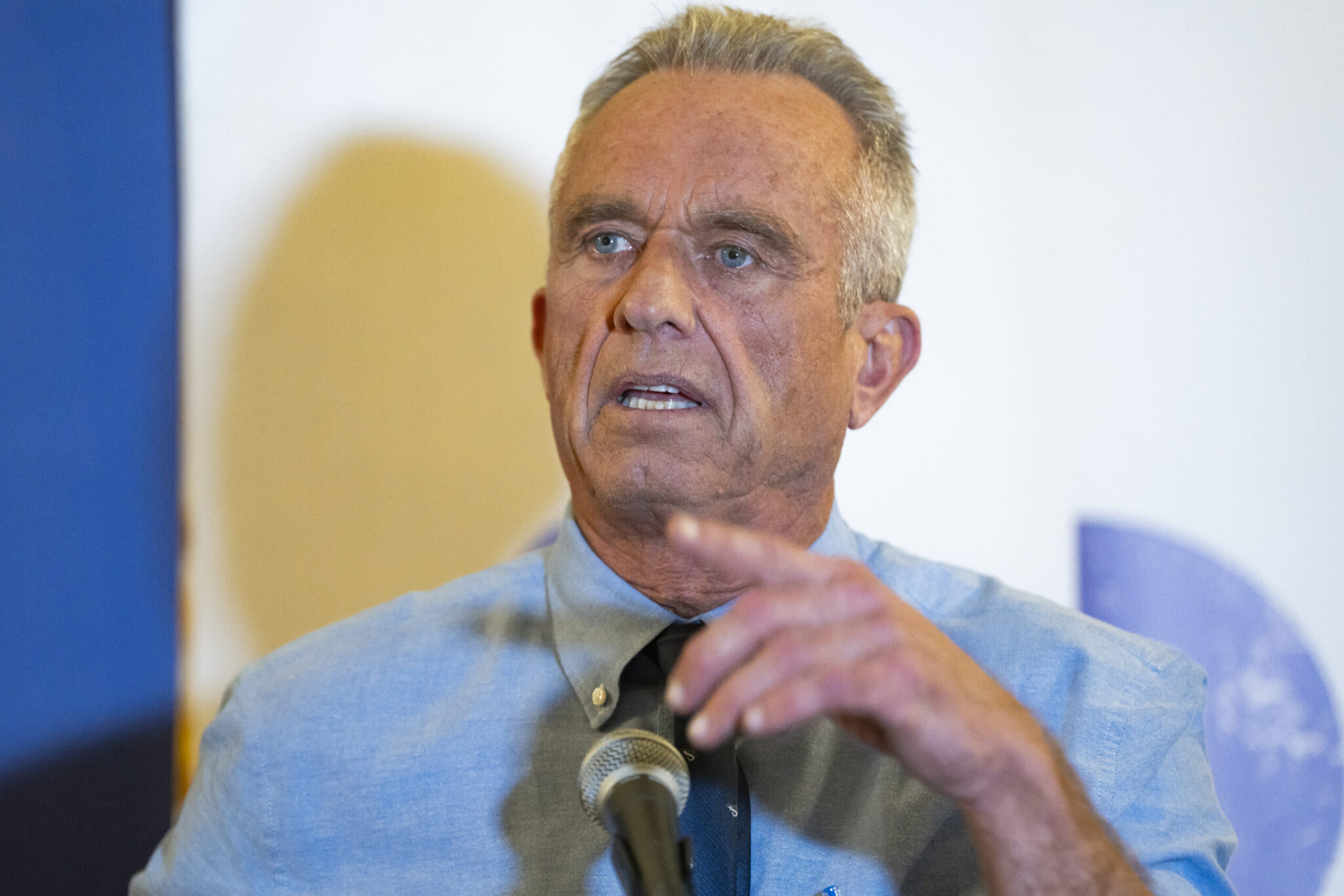

He honored the conditions, earned his release from probation a year early and left South Dakota behind — until this week, when his long and strange trip through life brought him back to the state (in name, at least) as a presidential candidate.

His campaign said it turned in 8,000 petition signatures, more than the 3,502 needed from registered South Dakota voters to make the ballot as an independent. The Secretary of State’s Office is reviewing the signatures for authenticity.

A brain worm, a dog (or goat) and a bear

Walsh, now 84, said he stayed in touch with Kennedy for a long time, though not as much lately. Still, Walsh said he accepted an invitation to the launch of Kennedy’s presidential campaign last year, when Kennedy was seeking the Democratic nomination before switching to run as an independent.

Walsh has always felt sympathy for the trauma Kennedy endured during and after the assassinations of his father, U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, and his uncle, President John F. Kennedy. Walsh also respects RFK Jr.’s work as an environmental lawyer and agrees with some of his political views.

But, Walsh added, “Every time I think he makes sense, the next day he’s got a worm in his head, or he’s eating a dog or putting a dead bear in Central Park.”

Those are all references to news stories about Kennedy from the past several months.

In May, The New York Times obtained a copy of a deposition Kennedy gave in 2012, when he said earlier bouts of memory loss and mental fog were diagnosed as “a worm that got into my brain and ate a portion of it and then died.” He has since learned that the parasite “was not the issue” with his brain, he said, and that it was actually related to metal toxicity from mercury.

The dog-eating accusation was in a July 2 story in Vanity Fair. Kennedy said the animal in the photo obtained by the magazine was a goat he ate during a river trip in Patagonia.

Last Sunday, Kennedy was forced to admit ahead of reporting by The New Yorker that he left a dead bear cub in Manhattan’s Central Park in 2014 because he thought it would be “amusing.” He picked up the roadkill while driving through the Hudson Valley and intended to eat it, he said, but got busy and left it in the park instead. When the bear was found that year, it sparked a media sensation and a mystery that wasn’t solved until Kennedy’s admission this week.

Still more baggage

That’s a small sample of Kennedy’s alternately tragic, inspiring, bizarre and troubling life and times. The more concerning incidents include his rampant spreading of vaccine misinformation — such as his false statement that “there’s no vaccine that is safe and effective” — and an allegation that he forcibly groped a woman in her 20s who was working for the Kennedy family as a babysitter during the 1990s. Kennedy has since apologized “for anything” he may have done to the woman but said he has “no memory” of the incident.

Four decades after his drug conviction in Rapid City, Kennedy says he remains in recovery from addiction. He deserves credit for that. But his other personal baggage weighs heavily on some voters who might otherwise be strongly inclined to support a Kennedy for president.

Just ask Bill Walsh, who’s still very Irish, Catholic and Democratic, and still fond of RFK Jr. and the broader Kennedy legacy.

None of those loyalties will convince Walsh to support Kennedy if his name is on the ballot Nov. 5.

“I’m not going to vote for him,” Walsh said.