(Amanda Hernández/South Dakota Searchlight)

Max Gruver spent the early morning hours of Sept. 14, 2017, heavily intoxicated and passed out on a couch inside the Phi Delta Theta chapter house at Louisiana State University.

He had been forced to repeatedly chug 190-proof Diesel liquor in a hazing ritual called “Bible Study,” during which pledges are quizzed on fraternity facts. The incident caused Gruver, a freshman majoring in political communications, to inhale his own vomit into his lungs.

By the time fraternity members finally sought medical aid the next morning, Gruver’s pulse was weak and they couldn’t tell if he was breathing. Gruver’s blood alcohol level was .495, more than six times Louisiana’s legal driving limit, when he died from what an autopsy concluded was “acute alcohol intoxication with aspiration.” He was 18.

As college students begin a new semester this fall, many will participate in rituals to bring in new members of a Greek fraternity or sorority, a sports team or other club. Sometimes, the initiations involve heavy alcohol use or physical assaults. Although awareness of hazing and its dangers has grown significantly, it still happens.

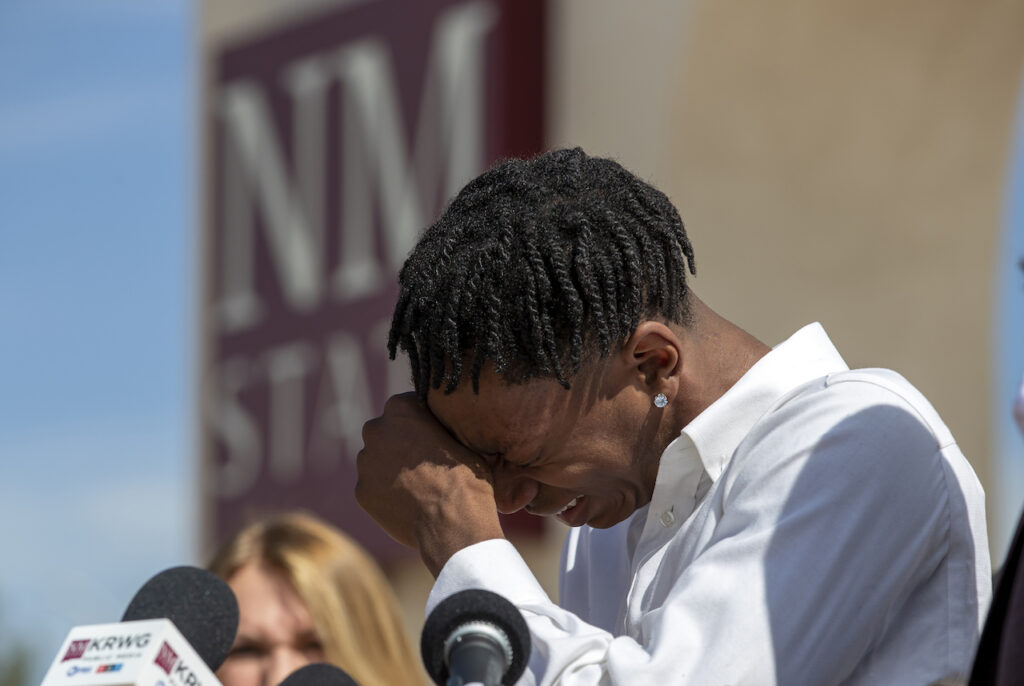

In June, New Mexico State University agreed to pay $8 million to settle a lawsuit over hazing allegations in the men’s basketball program. Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said she will be introducing anti-hazing and abuse legislation next year. In July, Northwestern University fired its head football coach after an investigation found widespread hazing on the team. And Boston College suspended its swim and dive team this month following hazing allegations.

At least 44 states and the District of Columbia have anti-hazing laws in place, most recently Ohio in 2021 and Pennsylvania in 2018. Kentucky and Washington strengthened their laws this past legislative session. Six states — Alaska, Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, South Dakota and Wyoming — have none, according to StopHazing, an anti-hazing advocacy and research organization.

SD bill failed; state laws differ

A bill to define criminal hazing passed the South Dakota Senate in 2022 but failed in a House committee. Sen. Michael Rohl, R-Aberdeen, was the sponsor. During a committee hearing, he distributed information about hazing incidents that occurred at schools including his alma mater, Drake University, in Iowa.

“It’s absolutely not acceptable in any capacity to think that institutionalized bullying is acceptable,” Rohl said during his testimony on the bill.

Wednesday, Rohl said some permissive attitudes among legislators toward hazing contributed to the bill’s demise. He did not re-introduce the bill this year but said he’d be willing to support a bill next year if somebody in the House would sponsor it.

State anti-hazing laws, most of which were approved in the past 15 years, differ in their definitions and the criminal penalties they impose. Depending on the state, participating in hazing activities may result in a fine, misdemeanor charge or a felony charge if the hazing results in serious bodily harm or death.

Some experts and anti-hazing advocates say the penalties in some states aren’t harsh enough to deter organizations from participating in hazing. And even in states that have laws, incidents like the one that left Max Gruver dead don’t necessarily lead to serious criminal charges.

Four former LSU students and ex-members of Phi Delta Theta were indicted in connection with Gruver’s death. Three of them faced misdemeanor hazing charges, while the fourth faced a felony charge of negligent homicide. The university also banned Phi Delta Theta from its campus until at least 2033.

Gruver’s parents — Rae Ann and Stephen Gruver — pressed for stiffer penalties for hazing, prompting Louisiana to enact the Max Gruver Act in 2018, which made hazing that results in serious bodily harm or death a felony; introduced a statewide definition of hazing; and mandated that hazing incidents and disciplinary actions taken against members of student groups be reported to the respective host institutions.

“It’s unfortunate that with the death of our son — it took that to get Louisiana to change their laws,” Stephen Gruver told Stateline. “It’s something that can be prevented; this never should have happened to our son.”

Since then, the Gruvers, along with parents of other hazing victims, have advocated for stricter state and federal penalties for hazing and greater transparency when such incidents occur.

“If you don’t have a strong enough law, it’s not a deterrent for these kids and they’re just going to keep on being bad actors because they just don’t care,” Stephen Gruver said.

Hazing’s wide reach

Hazing, a practice rooted in tradition and camaraderie, has long been a controversial and pervasive issue on college campuses. While hazing incidents have garnered significant national attention over the past decade, the earliest account of hazing is believed to date back to the fourth century — when Plato observed young boys playing “practical jokes” on other students in school, according to a book written by journalist and anti-hazing advocate Hank Nuwer. The first anti-hazing law in the United States was enacted in New York in 1894.

In the U.S., more than 280 people allegedly have died due to hazing since 1838, according to the U.S. Hazing Deaths Database. The database is maintained by Nuwer. Hazing deaths are not currently tracked by any U.S. government entity.

In 2017, the year of Gruver’s death, at least six other young adults also died a result of alleged hazing activities. Between 2018 and 2021, at least 23 people allegedly died due to hazing activities. No hazing deaths were reported in 2022.

According to a 2008 study by two University of Maine professors, more than half of college students involved with student organizations experience hazing, which often involves “alcohol consumption, humiliation, isolation, sleep-deprivation, and sex acts.” The study, which is considered the most comprehensive analysis of hazing in the United States, also found that about 47% of students come to college having already experienced hazing.

“Hazing is prevalent throughout society. It’s not just a college thing. It’s really seen anywhere that there’s a differing power dynamic,” Todd Shelton, the executive director of the Hazing Prevention Network, told Stateline. Hazing appears in settings such as high schools, other student groups, the military and professional workplaces.

In many states, hazing carries misdemeanor charges — a fact that some advocates argue does little to effectively deter hazing incidents.

“Where hazing is a minor misdemeanor, it’s not taken seriously by law enforcement because it’s not worth the effort to prosecute,” Shelton said. “One of the biggest hurdles is getting the penalty or statute to match the seriousness of the crime.”

In Kentucky, Lofton’s Law was signed into law in March, increasing the penalty for hazing that leads to death or serious physical injury to a Class D felony, punishable by up to five years in prison. Reckless participation in hazing can result in a misdemeanor.

And in Washington state, the Sam Martinez Stop Hazing Law, which was passed unanimously and signed into law in May, makes hazing a gross misdemeanor instead of a misdemeanor; if the hazing results in substantial bodily harm, it rises to a felony. The law bumps up penalties for hazing from a maximum of 90 days to up to a year — and up to five years for the felony charge.

Washington became the 15th state to elevate hazing to a felony if it causes severe injury or death.

“For the first time we’re talking about hazing in a very real way. There’s been a culture of secrecy, in my view, of hazing for many, many years,” Rep. Mari Leavitt, a Democrat who wrote the bill, said in an interview with Stateline. “Students will recognize that there is a pretty significant consequence for choosing to behave in these barbaric activities and it can change the trajectory of their lives.”

The new law follows the passage of Sam’s Law in 2022, named after the same student, which updated the definition of hazing and required universities and colleges, as well as fraternity and sorority chapters, to make hazing investigation records public.

“The more that people are aware, and willing to talk about it and willing to report what they see, that will start to change that culture of secrecy to something that holds people accountable and also is transparent in terms of what’s happening across states,” Leavitt said.

Anti-hazing movement

In 15 states, a major weakness in the anti-hazing law, according to StopHazing, is the absence of a “consent clause,” which asserts that an individual’s willingness to participate in potentially hazardous actions — as when a student agrees to a certain activity — does not protect those involved from hazing charges. Some anti-hazing laws explicitly spell out that consent is not a defense.

“The consent clause … is really important in terms of documenting hazing and having policy be really effective,” said Elizabeth Allan, the principal of StopHazing and a professor of higher education at the University of Maine. Allan co-wrote the 2008 national study on hazing.

Advocacy groups also have been pushing for national anti-hazing legislation to establish uniform definitions and penalties.

Proposed federal legislation, originally known as the Report and Educate About Campus Hazing Act, or REACH Act, was initially introduced in Congress in 2021. This year, it is set to be reintroduced under a new name, the Stop Campus Hazing Act. The legislation encompasses a range of transparency and prevention measures, including mandatory public reporting of hazing incidents and the implementation of comprehensive prevention programs.

“Hazing is often underreported, underrecognized and it’s really not being taken as seriously as it should be given the harmful impact that it has on individuals and communities,” said Jessica Mertz, the executive director of the Clery Center, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting campus safety.

Among Greek fraternities and sororities, discussions around cracking down on hazing have gained momentum. Still, critics argue that most state anti-hazing laws should impose tougher penalties on national Greek life organizations and institutions, rather than individuals.

“As a founding member of the Anti-Hazing Coalition, the North American Interfraternity Conference and our member fraternities advocate for stronger federal and state hazing laws to increase criminal penalties and provide greater transparency to hold individuals accountable when found to be involved in hazing,” Judson Horras, CEO of the North American Interfraternity Conference, said in a statement.

“While in this partnership, we have seen stronger state laws passed in over a dozen states and are encouraged by the introduction of the bipartisan Stop Campus Hazing Act in the 118th Congress last week,” the statement said.

A 2020 paper by a Penn State University professor and published in the Journal of College and University Law underscores this argument. Law professor Justin J. Swofford argues that for legislation to be most effective in deterring future hazing injuries and deaths, there must be greater criminal and civil penalties imposed on both schools and fraternities.

However, some voices within the Greek life community question whether genuine change is achievable. Lucy Taylor, who disaffiliated from Alpha Phi at the University of Maryland and hosts “SNAPPED,” a podcast exploring Greek life, suggests that change within Greek organizations can often appear performative.

These initiatives may encompass disciplinary committees, mandatory anti-hazing programs or even the hiring of security teams, Taylor said.

“They make it seem like change is happening, but those things that they’re doing to create change don’t actually have any power. If they wanted hazing to be gone, it would have been gone years ago,” Taylor said. “They don’t do anything or they don’t do what they’re intended to do, and the hazing culture just becomes even more secret.

“The more secret it becomes, the worse it gets.”