Jackie Hendry, SDPB, South Dakota News Watch

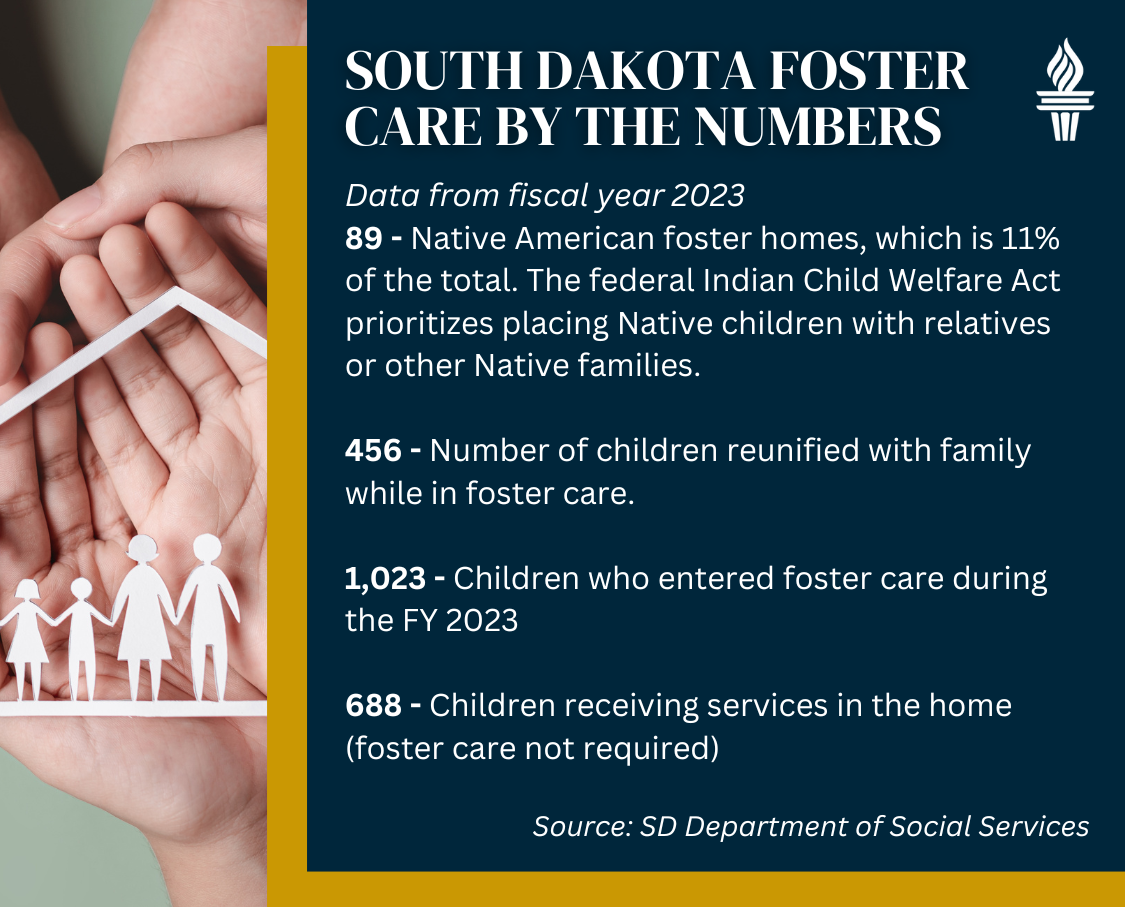

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. – South Dakota has more children in the foster system than families to care for them. On average, there were more than 1,000 children in the system in any given month last year but just over 800 foster families licensed statewide.

Children enter the system for a number of reasons, but the leading causes of foster placement in the state are neglect, parental substance abuse and parental incarceration, according to the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect.

The shortage of foster families is not a new problem.

In May 2021, Gov. Kristi Noem launched the Stronger Families Together initiative to highlight the need. In an email, a spokesperson for the Department of Social Services said 2,000 families have reached out for more information since the program’s launch, and 669 families have completed screening and training to become licensed foster care providers.

But the need persists.

“Foster families are needed in all communities across South Dakota, most critically in the western and central parts of the state,” the DSS spokesperson continued. “Foster families are needed for all ages and genders; however, there is a significant need for more Native American foster families. The Department also holds a need for foster families who can be available to care for sibling groups, older children, and children whose special needs require ongoing medical, mental health, and/or behavioral health care. Foster families capable of supporting services to address the developmental needs of children are also needed.”

Current foster families receive regular communication from the Department of Social Services on children who need placement options. Two foster families in the Sioux Falls area — where most foster families in the state are located — shared their stories in hopes of encouraging other families to get involved.

Serious problems are a small part of foster care

Tammy Vande Kamp is a nurse practitioner in the mental health field in Hartford. She initially learned about foster care from her husband’s family and then from a program at their church. Their first placement was a 10-day-old newborn they took home from the neonatal intensive care unit.

“He stayed with us for eight months, and then we were able to reunify him with his mom,” said Vande Kamp.

She and her husband have been foster parents for two years. Like many foster families, the Vande Kamps get regular emails from the Department of Social Services looking for placements for kids with nowhere else to go.

“I mean – we’re full. We have right now four foster children and two biological children living in our home, so we’re at capacity, and it’s sad,” said Vande Kamp.

She worries that press coverage of the foster system is too focused on the horror stories.

“We hear about the foster children that maybe run away. Or we hear about the foster parents that abuse the foster children or the kiddos that end up going home and they end up abused or unfortunately, maybe even they’re killed. It’s a very, very small part of foster care,” Vande Kamp said. “We have been fortunate to have some beautiful children in our home. Yes, there are challenging times. Yes, we have hard times, they have hard times. But there is so much good that comes out of them and us.”

Attachment to foster family helps kids later in life

While the common stigmas about foster care are likely one deterrent for potential foster families, another source of hesitation Vande Kamp often hears is a fear of getting too attached.

“I used to feel the same way,” she said. “I learned through classes and through the program that we were teaching them how to be attached. We’re trying to teach these children to attach so that when they’re older, when they’re adults, they can attach to other people. They can trust people.”

Vande Kamp said she was sad saying goodbye to her first foster child, but she was also happy to reunify him with his mother.

“I had a peace knowing that we gave him what he needed for the time he was with us,” she said. “I knew that we gave him the best of us that we could give him, and we gave him a good start for her to then continue on.”

There are several Facebook groups for foster parenting, including one Vande Kamp joined for foster parents in Minnehaha and Lincoln counties. She consistently saw posts asking for a support group for foster parents.

“So we started one,” said Vande Kamp.

Communities challenged to lend support beyond toys

What began as a gathering at a Scooters coffee shop now is a monthly meeting at Tre Ministries in Sioux Falls. She acknowledges it can be a safe place to vent, but it’s mostly an opportunity for foster parents to get advice from each other about state forms and available services.

“Because you can ask your social worker, but sometimes they’re busy and they don’t have time to call you back,” said Vande Kamp. “And for me personally, my best resource has been other foster moms who have been in this longer than I have.”

The informal support group is one kind of resource Vande Kamp sees lacking for foster families and the children they care for.

“I think we have great resources for things. We have great resources for clothes, diapers, toys,” said Vande Kamp. “We don’t have great resources for people.”

For example, Vande Kamp said she’d love to see a movement to provide frozen meals for foster families to occasionally ease the burden of meal prep on top of other obligations. More than that, she wants to see communities rise to the occasion to serve children in need.

“One thing my children don’t need more of is toys. They don’t need more toys. They don’t need another blanket. And they don’t need another stuffed animal. They need people,” she said. “They need other adults in their lives who can be positive role models. And certainly the Native American population of children need positive Native American role models.”

Kinship care givers, licensed or unlicensed, who are caring for a child placed in the custody of Child Protection Services (CPS) are eligible for financial support through several state and federal-funded resources.

Funding includes reimbursement for initial clothing, a personal allowance to help with ongoing clothing and incidentals, child care, medical expenses and other special purchase costs that assist in meeting the child’s medical, educational, mental health, cultural, family, permanency or social needs.

Indigenous foster care in short supply

Native American children made up 74% of children in the state foster system as of May 2023. The federal Indian Child Welfare Act prioritizes placing Native children with relatives or other Native families. But of the 808 state-licensed foster families in South Dakota last year, just 86 were Native American.

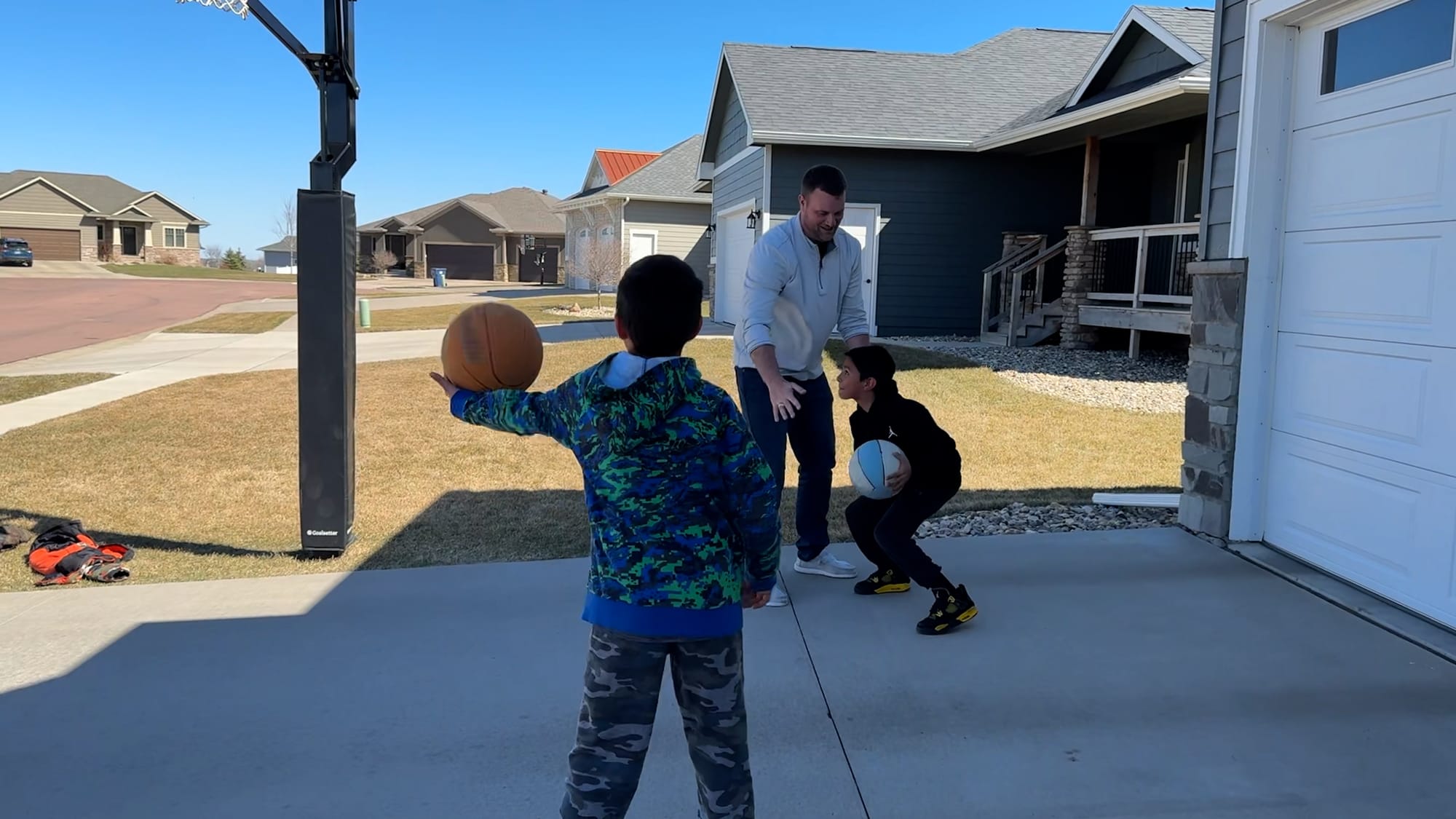

Brandy and Scott Louwagie of Sioux Falls were one of those families.

Brandy is a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. They’ve been fostering for 10 years and have almost exclusively had Native children placed with them. The Louwagies adopted their three children from foster care and were fostering an infant girl earlier this month.

“The responsibility that comes with being an ICWA home is just making sure those children, if they’re connected with their culture, to continue that connection,” said Brandy. “And if they’re not, introduce them to that side of their culture so that if they are seeking that when they’re older or something, it’s not something brand new to them when they’re trying to seek that heritage.”

Brandy said her Native identity has helped her develop a rapport with the birth relatives of some foster placements.

“The primary goal is always reunification of a child with their biological family,” she said. “As foster parents, it’s our job and our duty to help with that.”

Brandy and Scott work for Daktronics, and both travel frequently for their role. One resource they rely on is child care.

“If we didn’t have child care, there’s absolutely no way we could foster,” she said.

“It’d be too much impact on our lives,” he added. “We’d have to get new jobs.”

Benefit is worth the time commitment

Like other foster families, the Louwagies regularly receive emails and phone calls about children who need a place to stay.

“Our licensing person just came in to relicense us,” Brandy said. “You tell them as a foster home how many children you can accept. … So she says, ‘I know your hands are full, but can you take on more kids?’ And we’re like, we can’t. We do what we can, as much as we can. But she said, ‘We have so many children who need a placement.’”

The Louwagies also hear prospective foster parents worry about the time commitment or that they would get too attached to kids they’d ultimately return back to their families.

“We are so busy all the time,” said Brandy, gesturing to Scott. “I mean, we have sports, doctors’ visits, both of us travel — so pretty much one of us is always doing almost everything. And the thing is, yeah, the kids are what you love. That’s the only reason we do foster care is because of the kids.”

Both Brandy and Scott agree that they keep fostering because they value the chance to give children a sense of safety and security in a traumatic point in their lives.

“You just have to understand: If I can take the hurt of a child away, that’s what we’ll do,” Brandy said.