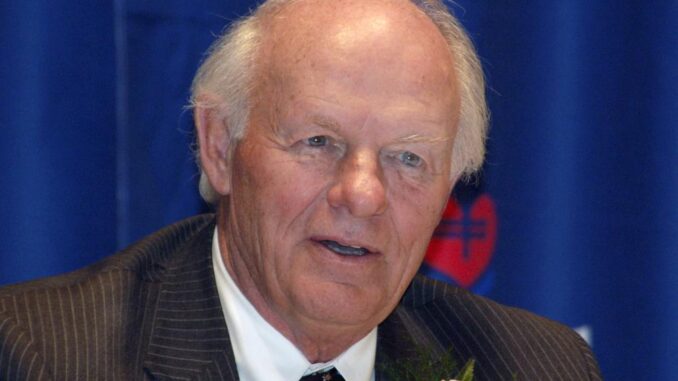

PIERRE, S.D. (AP) — The South Dakota Supreme Court Tuesday weighed whether to unseal a search warrant and affidavits in an investigation into billionaire banker-turned-philanthropist T. Denny Sanford for possible possession of child pornography.

The court documents are sealed and refer only to “an implicated individual,” and attorneys did not name Sanford as they made their arguments. However, one person briefed on the case by law enforcement told The Associated Press that the hearing involved Sanford and a legal effort by media organizations to unseal court records in the investigation. The person demanded anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the investigation.

The attorneys at the hearing also matched the lawyer representing Sanford, former South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley, and those for two media outlets — ProPublica and the Sioux Falls Argus Leader — that reported last year Sanford had been investigated for possession of child pornography.

Sanford has not been charged with any crime.

The 85-year-old is the state’s richest man, worth an estimated $2.8 billion, but has vowed to “die broke,” and his name adorns dozens of buildings and institutions in South Dakota and beyond.

Even after the investigation was reported last year, Sanford donated hundreds of millions of dollars to the South Dakota government and the state’s largest employer, Sanford Health. Some of the state’s top lawmakers, including Republican Gov. Kristi Noem, have not distanced themselves from Sanford.

ProPublica first reported that South Dakota investigators had obtained a search warrant, citing four unidentified sources. Two people briefed on the matter by law enforcement confirmed the investigation to the AP. They demanded anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss it.

Sanford’s electronic devices came to the attention of investigators with the South Dakota attorney general’s office after a technology firm reported that child pornography had either been sent, received or downloaded on his device, according to one of the people who spoke to AP.

Attorney General Jason Ravnsborg determined there was sufficient evidence to move toward prosecuting Sanford, but passed the case to the U.S. Department of Justice because it spanned to Arizona, California and Nebraska, according to both people. Federal prosecutors have given no indication that they are bringing charges against Sanford, and Ravnsborg has not dropped plans to prosecute him if the Justice Department declines, according to both people.

The Justice Department and the South Dakota attorney general’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the investigation.

Jackley argued Tuesday that South Dakota courts had ultimate authority over court records and should not heed a state statute that presumes them to be open to the public. He pointed out there has never been a complaint or indictment filed against the “implicated individual.” He said he could not comment on whether the case involved Sanford.

Jackley said in a statement after the investigation was reported last year: “Although we know very little about any state or federal inquiry relating to Mr. Sanford, we do know those authorities responsible for investigating allegations obviously did not find information or evidence that supported or resulted in any criminal charges.”

Jon Arneson, an attorney for the Argus Leader, told the state Supreme Court that the case boiled down to the public’s right to access court documents.

“This is a citizen, saying, ‘I want my name removed from it because it’s embarrassing,’” he said.

Immediately after the investigation was revealed, organizations, universities and governments stopped accepting Sanford’s donations. But in South Dakota — where his name adorns the largest employer, the largest indoor arena, and the largest charitable checks — the distancing was short-lived.

This year, Noem spearheaded an effort to create a scholarship endowment with $100 million from Sanford and First Premier Bank, the financial institution he founded. He attended a bill signing for it in March with Noem and several top state lawmakers.

First Premier is known for issuing high-interest credit cards to those with poor credit. Sanford, now retired, started it in 1986 amid a rush by lenders to take advantage of South Dakota’s lax lending laws.

Sanford told the AP in 2016 that he wanted his fortune to have a positive impact on children after his hardscrabble childhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. His mother died of breast cancer when he was 4, and by the time he was 8, Sanford was working in his father’s clothing distribution company. He, along with two siblings, lived in a small apartment.

Stanford has since given away close to $2 billion.

“You can only have so many cars and all of that kind of stuff so put it into something in which you can change people’s lives,” Sanford said in 2016.

Sanford Health CEO Bill Gassen announced in March that the billionaire was donating an additional $300 million to the hospital system that bears his name. He told South Dakota Public Broadcasting at the time that it took the reports of the investigation seriously, but was “satisfied that they were not substantiated.”

Sanford has given periodically to Republicans, including Donald Trump. In November 2019 — before the investigation was reported — Sanford donated $20,600 to a joint fundraising committee for Sen. Mike Rounds and the state’s Republican party, as well as $10,000 directly to the South Dakota GOP and $5,600 to Rounds’ reelection campaign.

Last year, he gave $6,000 to a fundraising committee for former Georgia Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler. The committee returned half of that, according to the Federal Election Commission.

But Sanford’s largest checks have gone to universities, health care organizations and children’s charities. He started his major charitable giving in 1999 with a $2 million donation to the Children’s Home Society of South Dakota, which aides victims of domestic violence, abuse and neglect. He has since given $69 million to the organization.

The state Supreme Court has not given a timeline on when it will rule on the case.