(STACKER) – Some of the most highly prized real estate in the U.S. exists in areas considered high risk for wildfires, flooding, or drought. Despite this present and growing danger, many Americans are still moving to climate-vulnerable regions.

This may be because some people are willing to take the risk if it means living in their dream home—an attempt to defy nature for one’s own hubris. To better educate prospective homebuyers, real estate brokerage site Redfin now provides a climate risk assessment for every property which includes flood, drought, heat, storm, and fire risk data at a glance. Even with the power of this information, homes with high fire risk are selling for $120,000 more than low-risk properties, per Redfin’s June 2022 report.

As housing demand increases, so, too, do the impacts of climate change. Homebuilders and homebuyers are expanding into vulnerable regions called the wildland urban interface—the area where real estate abuts or intermixes with natural land like forests or grassland. A forest without homes in or along the edge is just a forest. But when developers introduce commercial or residential properties, it becomes a wildland-urban interface, or WUI. The U.S.’s WUI, in terms of acreage, grew by 33% over 20 years. Nearly all of that growth resulted from new housing—roughly 14 million homes—being built in or along natural land.

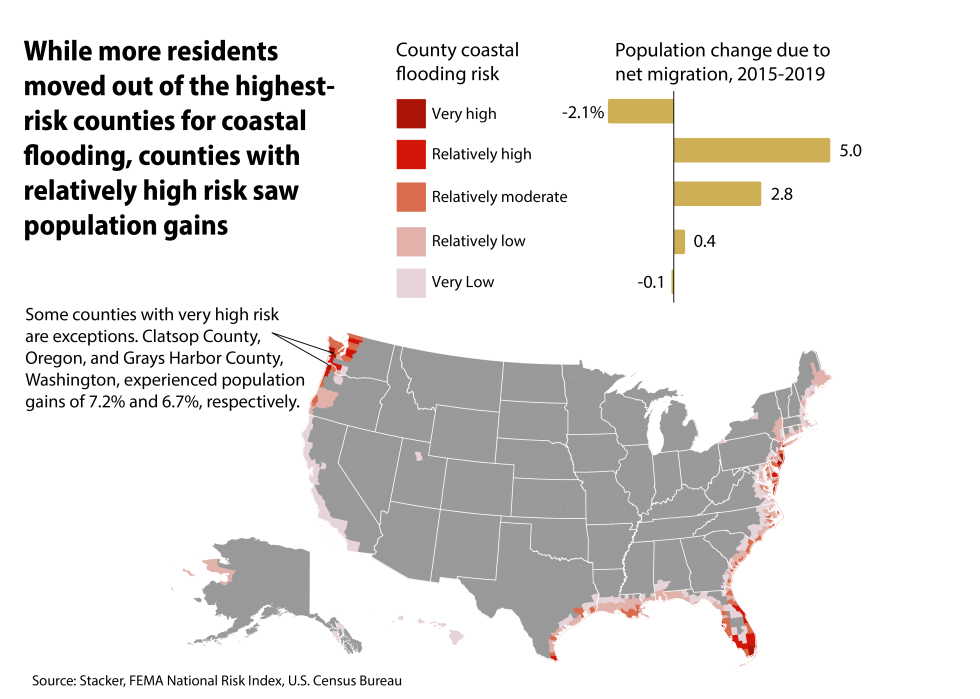

Housing along the U.S. coastline, especially the East Coast, is also at risk. Within the next 30 years, sea levels are projected to rise by up to a foot; within 80 years, up to 2 feet. A matter of inches within the scope of an entire coastline seems unsubstantial, but this increase will bring more intense flooding and storm surges. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, moderate flooding could happen 10 times as often in 2050 as it does today.

Mitigation efforts like governmental buyouts of homes in flood-prone regions can be one solution to this problem. It would cost the government $180 billion to purchase 1 million flood-prone homes across the country, according to a 2019 National Institute of Building Sciences report. Over 100 years, that would lead to a cost savings of more than $1 trillion that would have been paid out in flood insurance and disaster programs, which are federally subsidized.

Moving, either to a climate-vulnerable location despite the risks, or away from it for safety, is a form of privilege. A 2021 study published by the Environmental Protection Agency found coastal flooding, extreme temperatures, and poor air quality disproportionately affect minority and low income populations. And for populations already living in safe regions, climate gentrification—when affluent homebuyers move from climate vulnerable areas into new places, driving up home prices and changing the culture—is an indirect threat to their stability.

Experts predict that for much of the southern and southwestern U.S., a push north to more temperate climates is an eventual certainty for those with the necessary means, as climate change makes swaths of the country inhospitable and drives severe economic losses.

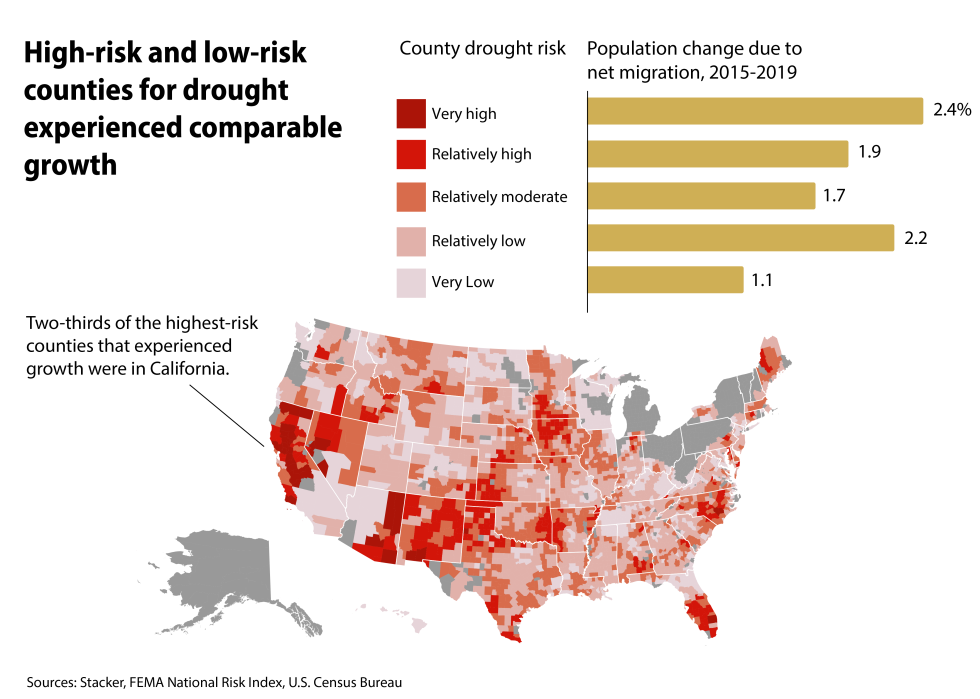

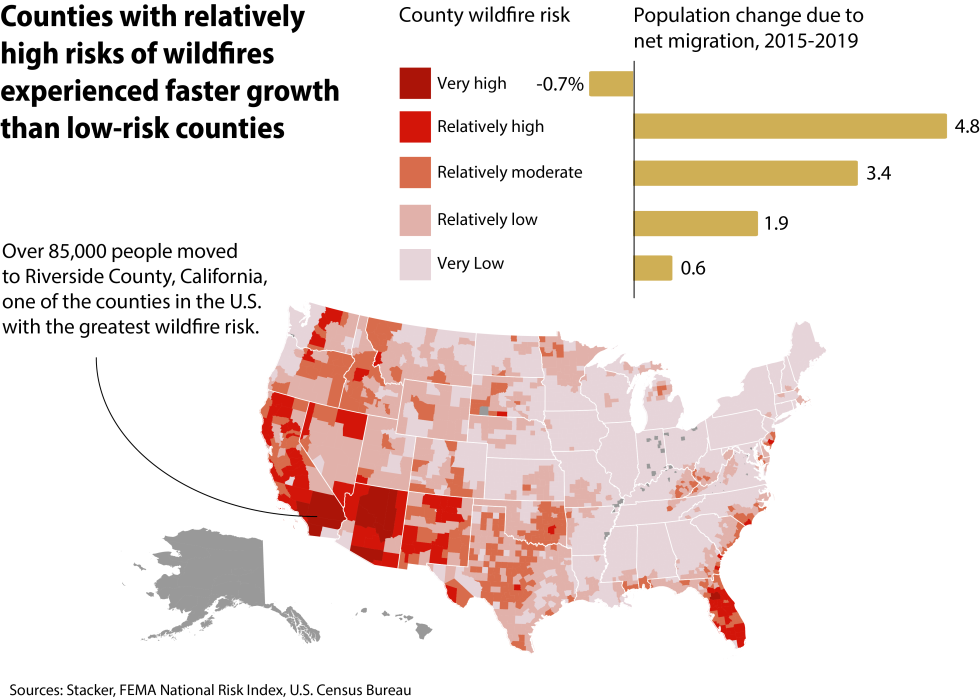

To better understand the climate-related threats Americans face, Stacker looked at population change due to migration in counties with the greatest and lowest climate risk between 2015-2019, citing Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Risk Index data and U.S. Census Bureau net migration data. We focused on 2015-2019 because the impacts of the pandemic meant abnormal net migration rates across much of the country.

Future flood risks to coastal regions under warming climate conditions have been well documented. And still, much of the East Coast has developed new housing in high-risk flood regions faster than in safer areas. In New Jersey, the worst offender of this trend, new housing development in coastal areas was three times higher than construction in inland regions.

In 2021, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Association of State Floodplain Managers petitioned FEMA to update its rules for building in floodplains—which have not been updated in more than four decades—to avoid devastating losses for future homeowners. The petition recommended mandating that all new construction happen beyond the 100-year flood zone, updating developers’ maps to show how the floodplain will change over time, and helping current owners retrofit their homes through flexible National Flood Insurance Program funding.

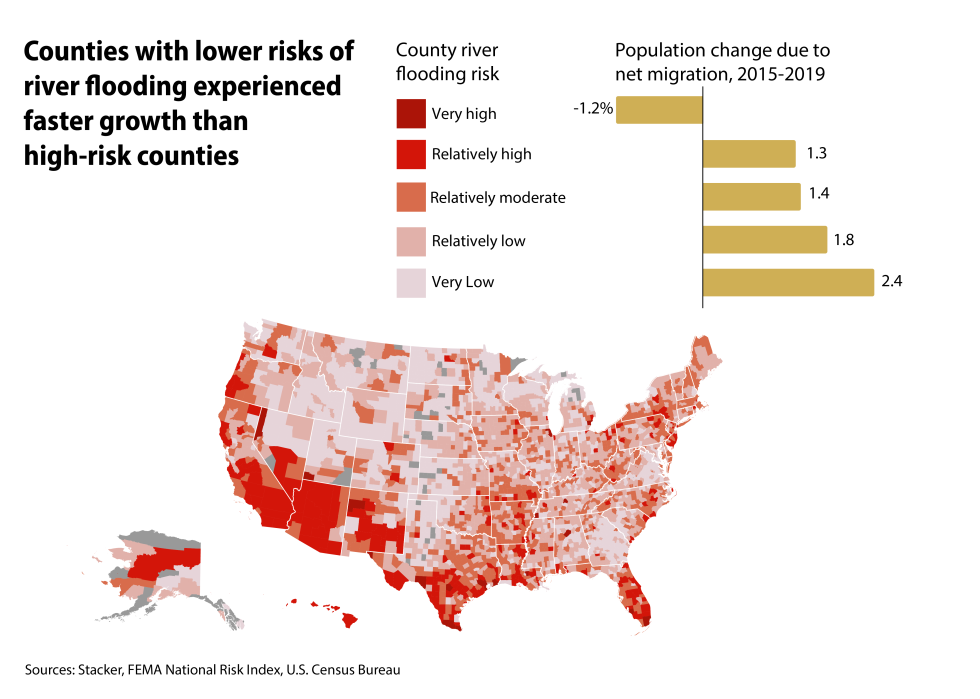

In many parts of the country, rivers are drying up due to climate-related precipitation changes and increased temperatures. Models predict that the Colorado River Basin—which extends from the Gulf of California to the Rocky Mountains and diverts water to major cities along the way—will see significant, and in some areas total, loss of critical snowpack and snowmelt runoff. In the Northeast and Midwest, heavier precipitation can lead to higher river volume and more frequent flooding.

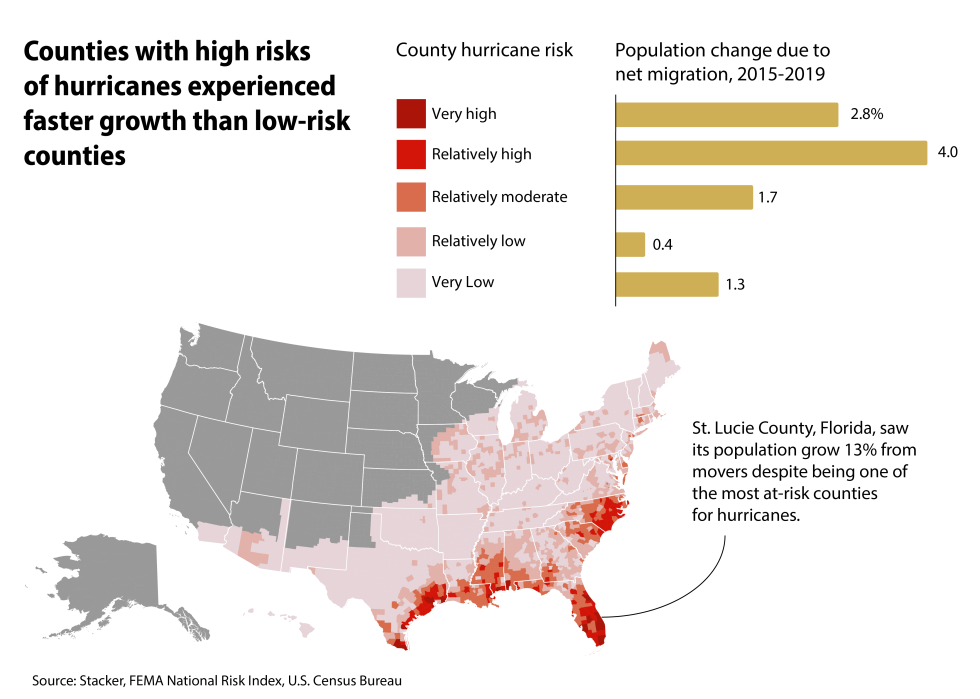

Between June 1 and November 30, the Gulf Coast states brace for the potential impacts of hurricane season. Like other climate-driven extreme weather events, hurricanes are becoming more frequent and intense. Historically, Florida has been more severely affected by hurricanes than any other state in terms of total monetary damage and emergency declarations. Between 2010 and 2019, the economic damage in Florida was more than $500 million per hurricane, totaling roughly $3.5 billion over the decade. In this same period, Florida made 14 hurricane-related disaster declarations.

According to NOAA, many coastal counties in Florida like St. Lucie will be underwater if sea levels continue to rise. Despite all this, the state’s real estate market remains one of the hottest in the country.

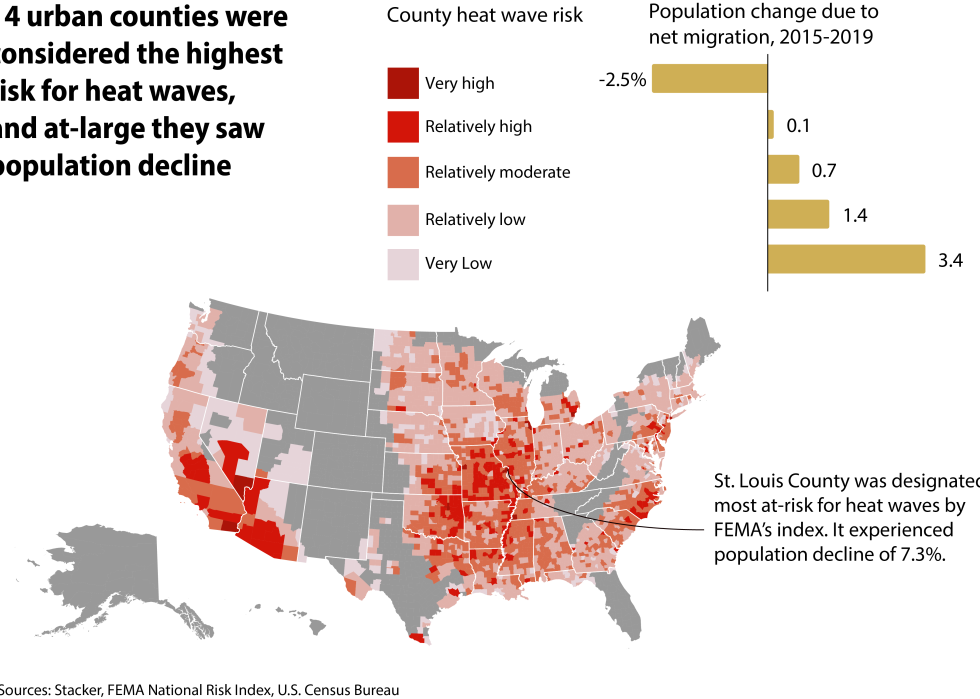

Heat waves in the U.S. are getting longer, hotter, and more frequent. Roughly 60 years ago, cities across the country averaged two heat waves per year. Today, the country averages more than six per year, and the heat wave season has extended by more than a month. Many of the regions at high risk for heat waves that saw a population decrease, as highlighted in the graphic above, were urban areas. It is difficult to isolate to what extent weather played a role in this exodus. However, scientists warn that the urban heat island effect, in which the release of heat from buildings and vehicles trapped by concrete and greenhouse gasses creates higher surface air temperatures in urban areas, will become more severe, making urban areas undesirable.

The U.S. is the driest it’s been in more than 1,500 years. The Southwest has been in the throes of a megadrought for 22 years, exacerbated by less frequent rainfall, lower soil moisture, and rising temperatures. Water stress creates ecological changes that can increase the risk for other extreme weather events like wildfires. The volume of drought-sensitive vegetation in a region, for example, can significantly affect the severity of a wildfire. In the path of a blaze, plants that are quick to dry out in the absence of moisture act like tinder.

According to a Fast Company study, places like the Sierra Nevada foothills, San Francisco Bay, San Diego, and San Antonio all have a high volume of drought-sensitive vegetation and have also seen a population increase in the WUI where that vegetation is most prevalent.

Wildfires in the U.S. have become more severe and more frequent due to climate change. Wildfires are four times larger and occur three times more often in the past two decades compared to the previous 20 years, according to a University of Colorado Boulder study. In addition to the problem of human ignition in the WUI, increased drought means wildfires are spreading faster and farther. Currently, 80 million properties across the country are at significant risk of fire exposure, and that number is growing. Over the next 30 years, nearly half of Americans will be living in fire-risk areas, particularly in the Mountain and West South Central regions.